Spirochetes are a unique phylum of bacteria characterized by their helical shape and internal motility apparatus. This article delves into the intricate anatomy of spirochetes, exploring how their structural components facilitate tissue penetration and contribute to the pathogenesis of diseases like syphilis and Lyme disease.

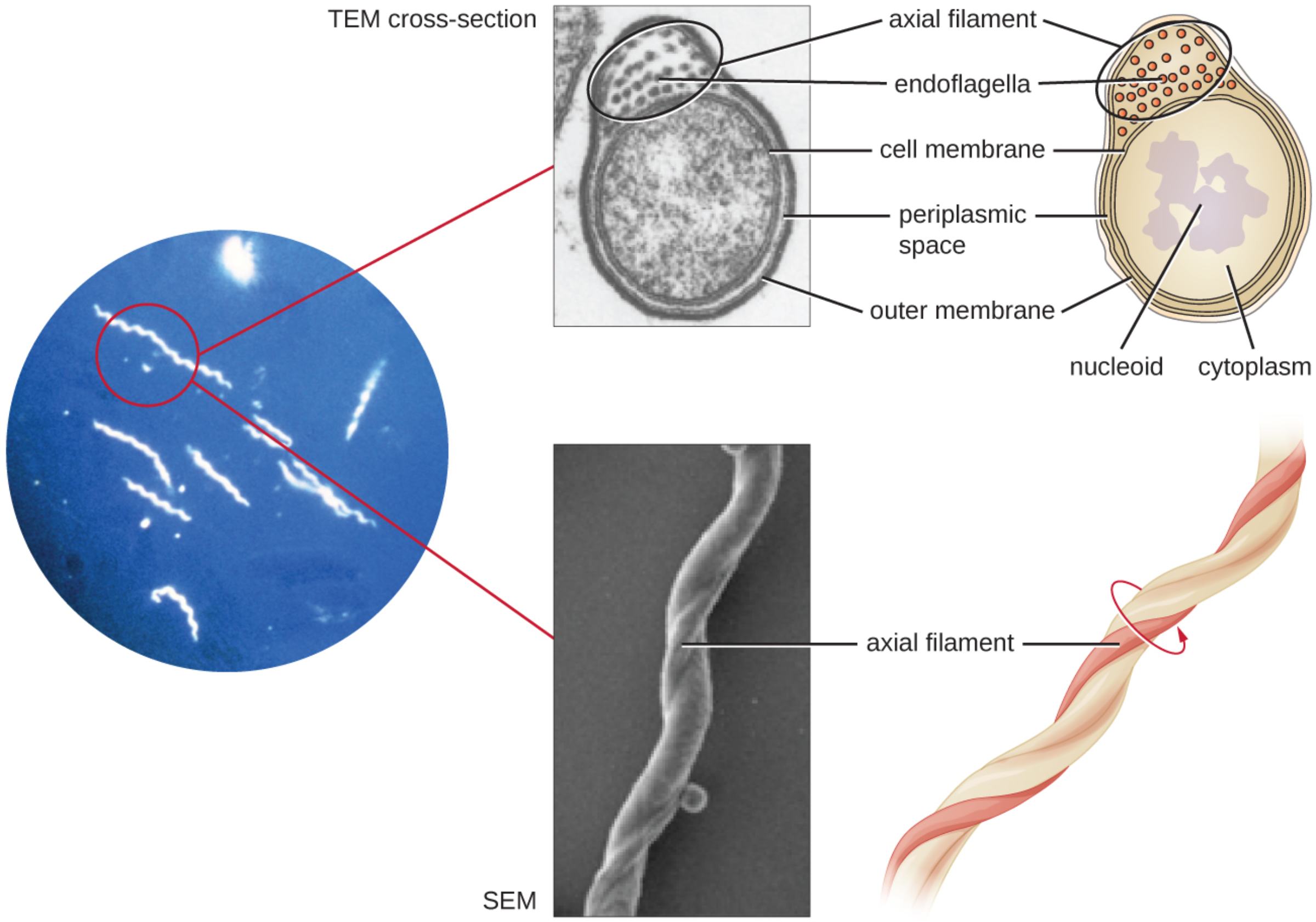

axial filament: This structure consists of a bundle of endoflagella that runs the length of the bacterium between the inner and outer membranes. The rotation of these filaments creates the torque necessary for the organism’s signature corkscrew motion.

endoflagella: These are specialized internal flagella that remain within the periplasmic space rather than protruding into the external environment. They are the primary organelles of locomotion, allowing the spirochete to move efficiently through highly viscous fluids.

cell membrane: The cell membrane serves as the inner lipid bilayer that encapsulates the cytoplasm and maintains the cell’s osmotic balance. It is also the site of essential metabolic processes, including electron transport and nutrient uptake.

periplasmic space: This is the compartment located between the inner cell membrane and the outer membrane. It houses the axial filaments, protecting them from host immune factors while providing the mechanical leverage needed for movement.

outer membrane: Often referred to as the outer sheath, this layer provides a protective barrier against environmental stressors and host immune responses. It contains specific lipoproteins that facilitate attachment to host cells and tissues.

nucleoid: The nucleoid is the concentrated region of the cytoplasm where the bacterial DNA is located. Unlike eukaryotic cells, this region lacks a nuclear envelope, allowing for the rapid transcription and translation of genes.

cytoplasm: This aqueous, gel-like substance fills the interior of the bacterial cell and contains ribosomes, enzymes, and various metabolites. It is the central hub for the biochemical reactions required for the cell’s growth and reproduction.

Spirochetes represent one of the most evolutionarily distinct groups within the bacterial kingdom. Their corkscrew-like appearance is not merely an aesthetic trait; it is a highly evolved anatomical adaptation that allows these pathogens to move through viscous media, such as mucus or connective tissue, where other bacteria might struggle. This mobility is powered by specialized internal structures that set them apart from common rod or cocci-shaped microorganisms.

In clinical diagnostics, visualizing these organisms can be challenging due to their thin cell walls, which do not always take up traditional stains effectively. Consequently, clinicians often rely on darkfield microscopy to observe live specimens from patient samples. This technique allows the bacteria to appear bright against a dark background, highlighting their rhythmic twisting motion and characteristic coils.

The structural integrity of a spirochete is maintained by its multi-layered cell envelope. While they share some similarities with Gram-negative bacteria, such as an outer membrane and a periplasmic space, the placement of their flagella is unique. Rather than protruding into the external environment, their locomotory organs remain tucked away, a strategy that may help them evade host immune detection for extended periods.

Key characteristics of spirochetes include:

- Helical or spiral cellular morphology.

- Endoflagella-driven “corkscrew” motility.

- Biphasic cell envelope with a protective outer sheath.

- Pathogenicity involving deep tissue invasion and systemic dissemination.

Pathogenesis and Clinical Impact

The unique anatomy of spirochetes is directly linked to the severity of the infections they cause. One of the most historically significant spirochetes is Treponema pallidum, the causative agent of syphilis. The bacterium’s ability to “drill” through the mucosal surfaces of the genital tract allows it to enter the bloodstream rapidly. From there, it can disseminate to the central nervous system or the cardiovascular system, leading to life-threatening complications if the infection is left untreated.

Another major public health concern is Borrelia burgdorferi, the primary organism responsible for Lyme disease. Transmitted via tick bites, this spirochete uses its internal axial filaments to migrate through the skin, often creating the characteristic “bullseye” rash known as erythema migrans. Its ability to navigate the dense extracellular matrix of human tissues allows it to persist in joints, the heart, and nerves, potentially causing chronic symptoms if it evades initial antibiotic therapy.

Physiology of Helical Locomotion

The movement of spirochetes is a marvel of biological engineering. When the endoflagella rotate within the periplasmic space, they exert torque against the rigid inner cylinder of the cell. This causes the entire bacterium to rotate in the opposite direction, creating a spiral wave that propels it forward. This mechanism is particularly effective in high-viscosity environments like the vitreous humor of the eye or the synovial fluid in joints, where traditional external flagella would be hampered by mechanical friction.

Beyond their physical movement, the physiology of these bacteria involves complex gene regulation to survive within different hosts. For instance, Borrelia species can alter their surface proteins depending on whether they are inside a tick or a human, a process known as antigenic variation. This adaptability, combined with their invasive physical structure, makes spirochetes some of the most resilient pathogens encountered in clinical medicine.

The sophisticated architecture of the spirochete cell underscores the importance of morphological adaptation in bacterial survival and disease progression. From the internal shielding of their endoflagella to their high-speed helical locomotion, every part of the spirochete is optimized for invasion. Ongoing research into these structures continues to inform the development of better diagnostic assays and therapeutic interventions for some of the world’s most persistent infectious diseases.

spirochetes, Treponema pallidum, Borrelia burgdorferi, Lyme disease, darkfield microscopy, axial filament, endoflagella, periplasmic space, electron microscopy, syphilis, Leptospira, bacterial motility, microbiology, pathogenesis, infectious disease