Spirilla represent a specialized class of bacteria distinguished by their rigid, helical structure and unique locomotive abilities. Often found in stagnant water and specific clinical environments, these microorganisms have adapted a spiral morphology that facilitates efficient movement through viscous fluids. Understanding the structural nuances of Spirillum is essential for both environmental microbiology and infectious disease diagnosis.

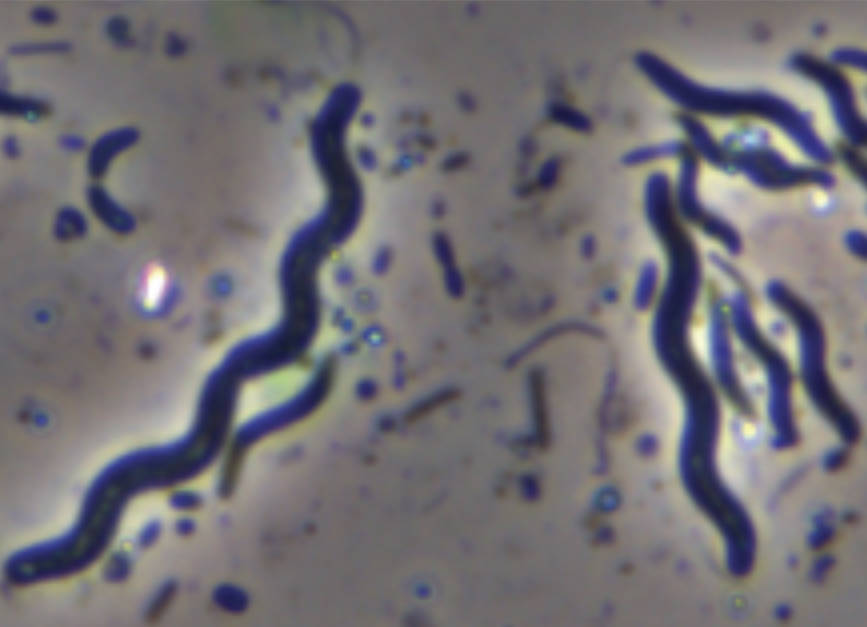

Spirillum: This term refers to a bacterium with a rigid, helical or corkscrew-shaped body. The structural rigidity is maintained by a dense peptidoglycan cell wall, allowing the organism to keep its wavy form during movement.

Spiral body: The elongated, twisted shape of the cell is designed to minimize drag while swimming through fluid media. This morphology is often associated with the presence of flagella at the poles, which propel the cell in a rotating fashion.

The study of bacterial morphology reveals a diverse array of survival strategies, with the spiral shape being one of the most mechanically interesting. Unlike the more common spherical or rod-shaped bacteria, Spirilla exhibit a fixed helical geometry. This shape is not merely a visual trait but a functional adaptation that allows these organisms to inhabit unique niches, such as stagnant freshwater or the mucosal linings of various hosts.

In the microscopic image, the distinct wavy lines represent individual Spirillum cells. Their structural integrity is primarily derived from a specialized cytoskeleton and a robust cell wall. This rigidity distinguishes them from spirochetes, which are flexible and use a different mechanism for movement. Spirilla typically move using polar flagella—whip-like appendages located at the ends of the cell that rotate like propellers.

Characteristic traits of Spirillum include:

- Rigid helical cell shape that does not change during locomotion.

- Possession of tufts of flagella (lophotrichous) at one or both poles.

- Generally aerobic or microaerophilic metabolism.

- Commonly found in organic-rich aquatic environments.

From a taxonomic perspective, the genus Spirillum belongs to the family Spirillaceae. While many are harmless environmental microbes, certain spiral-shaped bacteria are of great medical significance. Understanding their anatomical structure is the first step in differentiating beneficial species from those that may cause illness in humans and animals.

Anatomical Engineering and Physiological Adaptation

The physiology of Spirilla is deeply tied to their environment. Their spiral morphology acts like a drill bit, allowing them to penetrate through thick substances. This is facilitated by chemotaxis, a process where the bacteria sense chemical gradients in their surroundings and move toward nutrients or away from toxins. The internal structure of these cells includes a cytoplasm rich in ribosomes and a nucleoid region where the circular DNA is located.

One of the most fascinating aspects of spiral bacteria is their cell envelope. Most members of this group are Gram-negative, meaning they possess an outer membrane rich in lipopolysaccharides. This outer membrane serves as a selective barrier, regulating the entry of antibiotics and protecting the cell from environmental stressors. Inside this, the thin peptidoglycan layer provides the necessary tensile strength to maintain the helical shape under high internal pressure.

In clinical microbiology, recognizing the “S” or “comma” shape of a bacterium can lead to the rapid diagnosis of specific conditions. For example, Helicobacter pylori, which shares a similar curved or spiral morphology, is the leading cause of gastric ulcers. By studying the mechanics of how these bacteria move and attach to surfaces, researchers can develop more effective treatments that interfere with their ability to colonize host tissues.

The rigid spiral shape of Spirilla is a testament to the intricate relationship between biological form and function. These microorganisms have evolved highly specialized structures to thrive in challenging environments, using their helical bodies to navigate with remarkable precision. As we continue to refine our microscopic and genomic tools, the study of spiral bacteria will remain a vital component of our understanding of both the natural world and the complexities of human pathology.