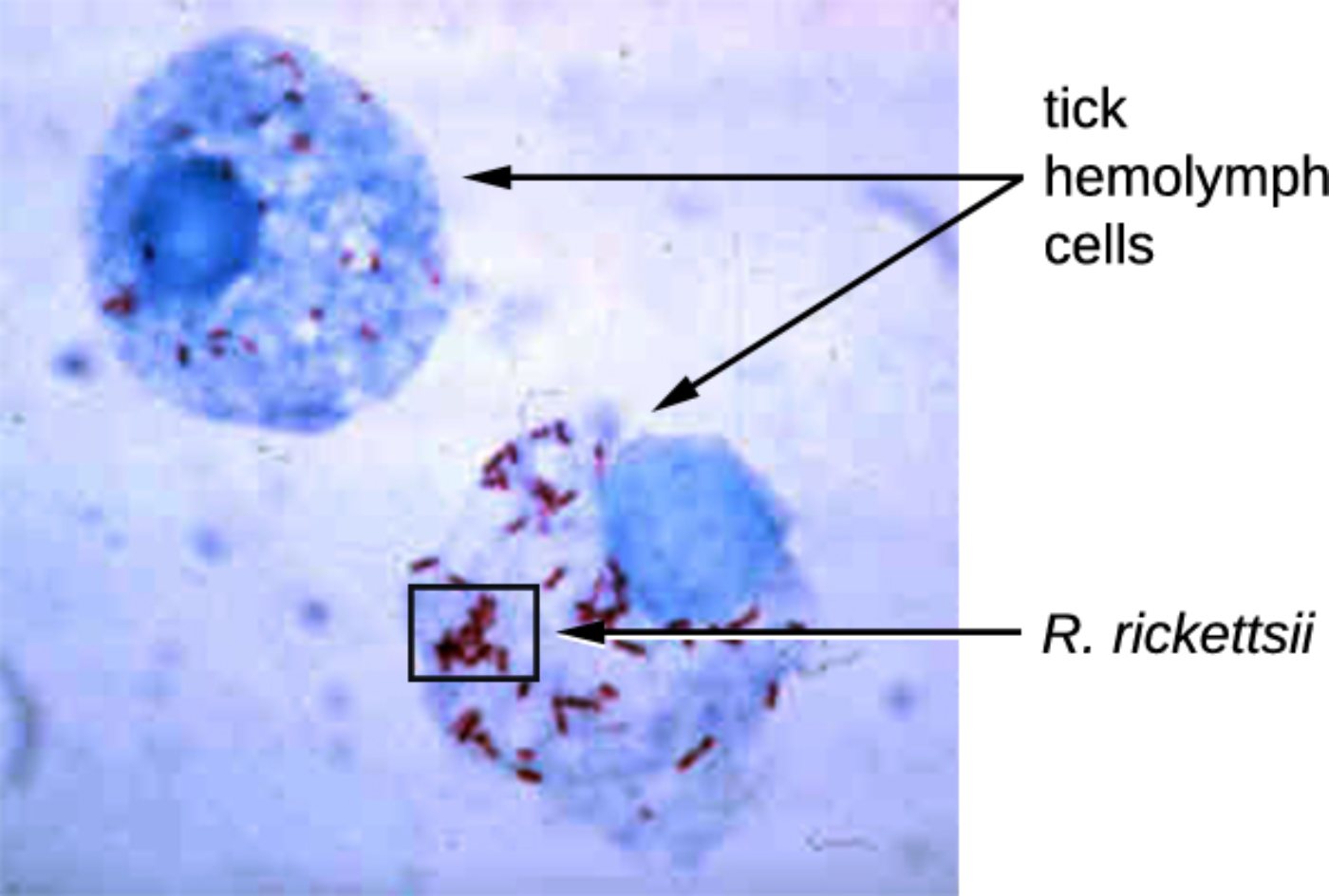

Rickettsia rickettsii is a specialized gram-negative bacterium recognized as the causative agent of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF). As an obligate intracellular pathogen, it must reside within the cytoplasm of a host cell to survive, replicate, and eventually transition to a new host via an arthropod vector. Microscopic visualization, as seen in tick hemolymph, provides a window into the initial stages of infection before the pathogen is transmitted to the human bloodstream.

tick hemolymph cells: These are the circulatory cells found within the hemolymph of an arthropod, serving immune and transport functions similar to vertebrate white blood cells. In the provided micrograph, these cells act as the primary host environment where the bacteria multiply before migrating to the tick’s salivary glands for transmission.

R. rickettsii: These small, coccobacilli-shaped organisms are the bacterial pathogens responsible for severe systemic disease in humans and other mammals. They appear as distinct red-stained rods within the blue-stained host cell, illustrating their reliance on intracellular resources for metabolic activity.

Rickettsia rickettsii belongs to the class Alphaproteobacteria, a diverse taxonomic group that includes some of the most specialized intracellular organisms in biology. Due to their unique evolutionary path, these bacteria have lost many genes required for independent survival, making them entirely dependent on the host cell’s ATP and nutrients. Because they are so small and possess a thin cell wall, they are notoriously difficult to see with a standard Gram stain; clinicians and microbiologists instead use specialized techniques like the Giemsa or Gimenez stain to reveal their presence within tissue samples.

The life cycle of this pathogen is inextricably linked to its tick vectors, primarily the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis) and the Rocky Mountain wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni). The bacteria are maintained in the tick population through transovarial transmission, meaning an infected female tick can pass the bacteria directly to her offspring. This ecological persistence ensures that the threat of infection remains present in endemic areas regardless of the availability of mammalian hosts.

When an infected tick attaches to a human, the bacteria are transferred through the saliva during a blood meal. This process usually requires several hours of attachment before the bacteria are successfully “activated” and transmitted. Once in the human body, the pathogen exhibits a high affinity for specific cell types, leading to the clinical manifestations that define the disease.

Key characteristics of R. rickettsii include:

- An obligate intracellular lifestyle that evades many traditional immune responses.

- A specific tropism for human endothelial cells lining the small blood vessels.

- The use of actin-based motility to spread directly from one cell to an adjacent cell.

- A requirement for specialized staining or molecular testing (PCR) for definitive diagnosis.

Clinical Pathology: Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF)

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever is considered the most severe tick-borne rickettsial illness in the United States. The primary pathological mechanism is widespread vasculitis, or inflammation of the blood vessels. As the bacteria infect and damage the lining of the vascular system, they cause small leaks in the vessels, which leads to the characteristic “spotted” rash and potentially catastrophic organ damage. If left untreated, the loss of vascular integrity can result in fluid shifts, limb loss due to necrosis, and fatal swelling in the brain or lungs.

The symptoms of RMSF typically begin 3 to 12 days after a tick bite, though many patients do not recall being bitten. Initial signs are often non-specific, including high fever, severe headache, and muscle pain, which can lead to frequent misdiagnosis as a common viral flu. The hallmark rash usually appears 2 to 5 days after the fever begins. This rash traditionally starts as small, flat, pink spots on the wrists and ankles before spreading centripetally to the trunk. A key diagnostic clue for RMSF is the presence of the rash on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet, a location rarely involved in other common rashes.

Because the disease progresses rapidly, healthcare providers must initiate treatment based on clinical suspicion alone, rather than waiting for laboratory confirmation. Doxycycline is the gold standard treatment for patients of all ages, including children, as it is the only antibiotic proven to be effective against the pathogen. Early administration of this medication is the single most important factor in preventing death and long-term disability.

The complex relationship between the tick vector, the R. rickettsii bacteria, and the human host highlights the intricate nature of vector-borne diseases. From the microscopic view of bacteria thriving in tick hemolymph to the systemic challenges of human vasculitis, this pathogen remains a significant focus of public health and infectious disease research. Vigilance, tick prevention, and early medical intervention remain the most effective tools in managing the risks associated with this ancient and highly adapted parasite.