Phase-contrast microscopy is a specialized optical imaging technique that transforms invisible phase shifts in light passing through a transparent specimen into brightness changes in the image. This method is essential in medical and biological research because it allows for the detailed visualization of live, unstained cells and microorganisms that would otherwise appear invisible under a standard brightfield microscope. By exploiting the differences in the refractive index between cellular structures and their surrounding medium, clinicians and researchers can observe physiological processes in real-time without killing or distorting the sample.

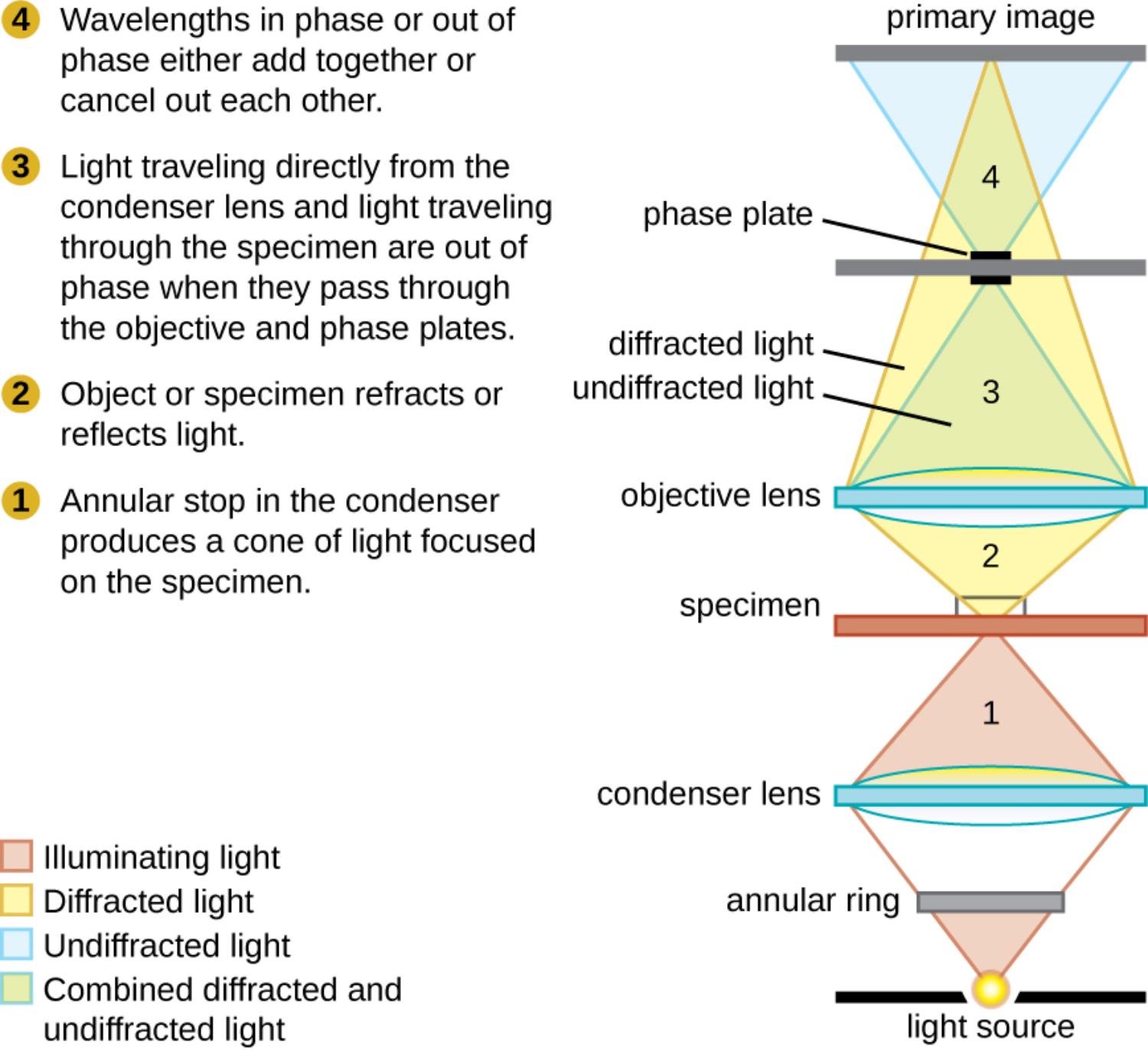

Light source: This component provides the high-intensity illumination required for the system to function. It emits light rays that travel upward toward the condenser, serving as the foundational energy that will eventually pass through the specimen and form an image.

Annular ring: Often referred to as the annular stop, this opaque plate with a transparent ring is located below the condenser lens. It blocks the central portion of the light beam, producing a hollow cone of light that focuses on the specimen, which is critical for separating direct light from diffracted light.

Condenser lens: Positioned between the light source and the specimen, this optical element gathers the hollow cone of light created by the annular ring. It concentrates these light rays onto the sample, ensuring that the specimen is illuminated evenly and at the correct angle to facilitate phase changes.

Specimen: This is the biological sample, such as a tissue culture, blood smear, or bacterial colony, placed on the microscope stage. As light passes through the specimen, the varying densities and thicknesses of its internal structures cause the light waves to refract and shift in phase.

Objective lens: Located above the specimen, this lens collects the light that has interacted with the sample as well as the background light. It is responsible for the initial magnification of the image and directs the light paths toward the phase plate.

Undiffracted light: Represented by the blue shading in the diagram, this is the background light (also called direct or surround light) that passes through the specimen without interacting with any structures. Because it does not encounter any obstacles, it travels directly through the objective lens to the phase plate.

Diffracted light: Indicated by the yellow shading, these light rays have interacted with the specimen and been scattered or bent (refracted) by cellular structures. These rays are retarded in phase compared to the direct light because they have passed through denser biological matter.

Phase plate: This critical component is usually built into the back focal plane of the objective lens and contains a phase ring that matches the annular ring in the condenser. It selectively advances or retards the phase of the undiffracted light by a quarter wavelength, increasing the contrast between the background and the specimen.

Primary image: This is the final visual result formed at the image plane where the diffracted and undiffracted light beams recombine. Through the process of interference, the invisible phase differences are converted into amplitude differences, creating a high-contrast image where the specimen appears dark against a light background or vice versa.

Understanding the Mechanics of Phase-Contrast

Phase-contrast microscopy was developed to solve a fundamental problem in biology: living cells are largely composed of water and are transparent, making them difficult to distinguish from the surrounding medium. In standard microscopy, light passes through these transparent objects without losing intensity, resulting in a washed-out image. However, while the intensity (brightness) doesn’t change, the speed of light does change as it passes through thicker or denser parts of the cell, such as the nucleus or mitochondria. This causes the light waves to shift their “phase,” appearing slightly behind the light waves that merely passed through the water.

The phase-contrast microscope converts these minute, invisible phase shifts into visible changes in brightness (amplitude). As shown in the diagram, the separation of light into diffracted (scattered by the sample) and undiffracted (background) paths is the key. When these two paths interact at the phase plate, the background light is sped up or slowed down further. When the beams eventually recombine to form the primary image, they interfere with each other. If the wave peaks align, the image brightens; if a peak meets a trough, they cancel out, creating darkness. This optical manipulation renders transparent structures visible in high contrast.

This technology is indispensable in clinical and research settings because it eliminates the need for staining. Chemical staining typically kills cells and can introduce artifacts that distort the true structure of the specimen. By avoiding these harsh treatments, phase-contrast microscopy preserves the natural physiological state of the sample, allowing for the observation of movement and life cycles.

The primary advantages of this optical system include:

- Live Cell Imaging: Enables the observation of motility, cell division (mitosis), and phagocytosis in real-time.

- High Resolution of Intracellular Structures: Clearly reveals organelles such as nuclei, mitochondria, and vacuoles without dyes.

- Reduced Artifacts: Minimizes the risk of misinterpreting structures caused by fixation or staining protocols.

- Rapid Diagnosis: Allows for immediate examination of wet-mount samples in clinical environments, such as urine or blood analysis.

Clinical Utility and Physiological Analysis

In the medical field, phase-contrast microscopy is a standard tool for evaluating biological fluids and tissues. One of its most common applications is in the analysis of urine sediments. In a clinical laboratory, technicians use this technique to distinguish between hyaline casts, red blood cells, and dysmorphic cells that may indicate kidney disease. Because hyaline casts have a refractive index very similar to urine, they are easily missed under brightfield illumination but appear distinct and clearly defined under phase-contrast.

Furthermore, this technique is vital in the field of andrology for semen analysis. Assessing sperm motility and morphology requires viewing live cells to determine viability. Phase-contrast optics provide the necessary contrast to visualize the distinct parts of the sperm cell—the head, midpiece, and tail—while they are moving. This allows clinicians to accurately assess fertility potential without processing steps that would stop the sperm’s movement.

The technique relies heavily on the concept of refractive index, which is a measure of how much a substance slows down light. Different organelles within a cell, such as the dense nucleus or the fluid-filled cytoplasm, have different refractive indices. When light traverses these structures, the optical path difference creates the phase shift. By manipulating these shifts through constructive and destructive interference, the microscope essentially creates a topography map of the cell’s density, presenting it as a detailed black-and-white image.

Conclusion

Phase-contrast microscopy represents a brilliant fusion of physics and biology, turning invisible optical properties into visible diagnostic information. By splitting light paths and manipulating their phases, this technology unveils the intricate details of transparent, living biological specimens that are otherwise invisible to the naked eye. From routine urinalysis to complex cell culture research, its ability to provide high-contrast images without lethal staining makes it a cornerstone of modern medical diagnostics and cellular biology.