Prokaryotic cells rely on a specialized architecture to survive in diverse fluid environments, utilizing a rigid cell wall to maintain structural integrity against osmotic stress. This article examines the physiological mechanisms of plasmolysis and the critical role of the cell membrane in balancing internal and external concentrations to prevent cellular collapse or rupture.

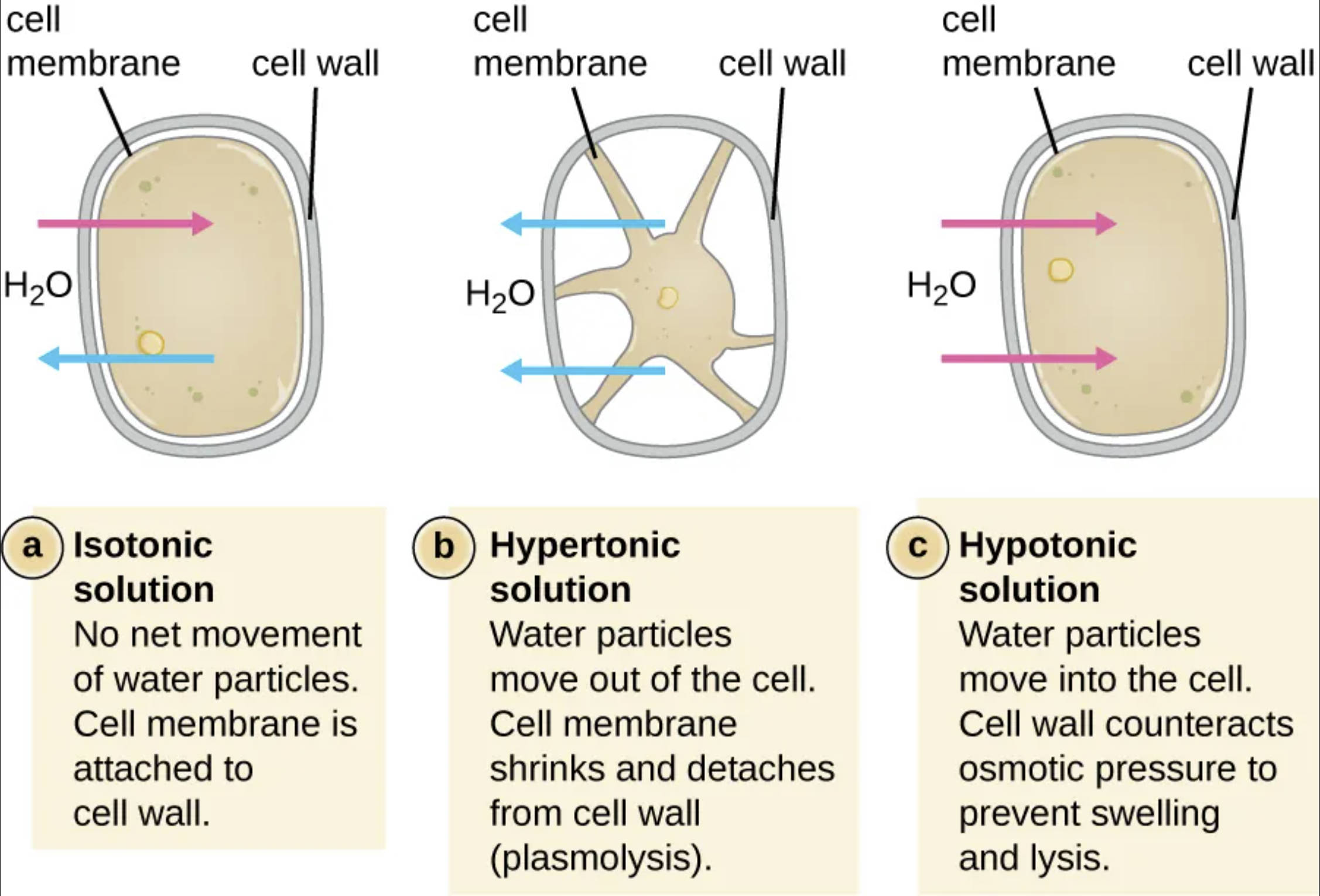

Cell membrane: This is the selectively permeable phospholipid bilayer that encompasses the cell’s cytoplasm and regulates molecular transport. In hypertonic environments, this structure contracts and pulls away from the exterior wall as the internal volume decreases.

Cell wall: This rigid outer layer is the primary structural component that maintains the cell’s shape and protects it from mechanical stress. It provides the necessary counter-pressure to prevent the internal plasma membrane from expanding beyond its physical limits.

H2OH2O: These symbols represent water molecules, which are the primary solvent involved in the osmotic process. The arrows indicate the direction of water flow, showing how it enters or exits the cell based on the external concentration gradient.

Prokaryotes, primarily bacteria and archaea, exist in environments with constantly shifting salt and sugar concentrations. To survive, they have evolved a robust cell envelope that acts as a physical barrier against fluctuating osmotic pressure. This structural defense is essential because, unlike most eukaryotic cells, prokaryotes often inhabit highly variable ecosystems where water availability and solute concentrations can change in an instant. The cell wall, typically composed of peptidoglycan, provides the mechanical strength needed to endure these shifts.

The movement of water across the cell membrane is governed by the principles of osmosis, where solvent moves from an area of high water concentration to an area of low water concentration. In an isotonic environment, the cell exists in a state of dynamic equilibrium with no net movement of water. However, extreme concentrations lead to either the shriveling of the cytoplasm or the intense swelling of the cell, both of which test the limits of the prokaryotic architecture.

Understanding these reactions is not just a matter of basic biology; it has significant implications in medicine and food safety. For instance, high salt or sugar concentrations are used in food preservation to induce plasmolysis in contaminating bacteria, effectively halting their growth. Clinically, understanding how osmotic stress affects bacterial cell walls helps in the development of certain antibiotics that target these very structures to induce cell death.

Fundamental osmotic states in prokaryotes include:

- Isotonic: Balanced solute concentrations where the membrane remains attached to the wall.

- Hypertonic: High external solute concentration leading to water loss and cytoplasmic contraction.

- Hypotonic: Low external solute concentration resulting in water influx and internal expansion.

Physiological Responses to Hypertonic Stress and Plasmolysis

When a prokaryotic cell is submerged in a hypertonic solution, the external osmolarity is higher than the internal environment. Because the cell membrane is permeable to water but restrictive to many solutes, water molecules begin to exit the cell rapidly. As the internal water volume drops, the cytoplasm shrinks, and the plasma membrane begins to detach from the cell wall, a process identified as plasmolysis.

This detachment is a critical event for the cell. While the rigid wall remains intact and retains the overall shape of the organism, the metabolic processes within the shrunken cytoplasm often slow down or stop entirely. This bacteriostatic state is why high-solute environments are effective at preventing bacterial spoilage; the cells are physically alive but functionally dormant due to extreme dehydration.

Hypotonic Environments and the Role of Turgor Pressure

In a hypotonic solution, the external environment has a lower concentration of solutes compared to the cytoplasm. Water flows into the cell, causing the cytoplasmic volume to expand and push the plasma membrane against the cell wall. This creates an internal force known as turgor pressure, which is essential for certain bacterial functions, including mechanical stability and growth.

The cell wall is remarkably effective at counteracting this internal pressure, preventing the cell from swelling to the point of rupture. However, there is a physical limit to this defense. If the osmotic gradient is too extreme, or if the cell wall is weakened by enzymes, the membrane will eventually expand through the gaps in the wall, leading to catastrophic lysis and cell death.

The relationship between the prokaryotic cell wall and membrane is a fundamental aspect of microbial physiology. By managing osmotic flow through selective permeability and mechanical resistance, prokaryotes can maintain their structural integrity across a wide range of environmental conditions. This ability to withstand osmotic stress is a testament to the evolutionary success of the prokaryotic cell plan, enabling these organisms to colonize almost every habitat on Earth.