Neisseria meningitidis is a highly infectious bacterium that remains a global health priority due to its potential for rapid clinical progression and high mortality rates. This professional overview explores the laboratory cultivation of meningococcus on specialized media and the physiological impact of the diseases it triggers in the human body, providing essential insights for clinicians and laboratory professionals alike.

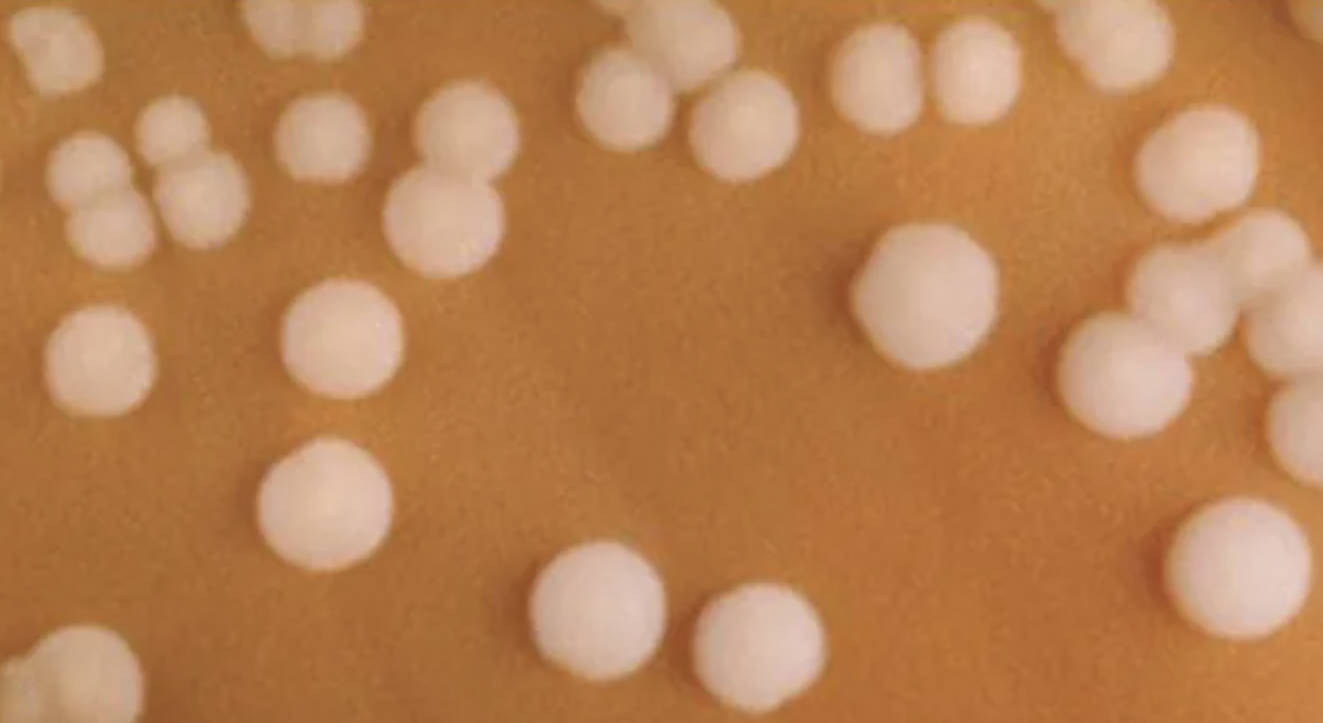

The image provided displays several small, circular, and convex colonies of Neisseria meningitidis growing on a specialized medium known as chocolate agar. These colonies typically appear smooth, moist, and glistening with a grayish-white hue, reflecting the characteristic morphology used by microbiologists to differentiate this pathogen from others. Because the organism is particularly sensitive to environmental changes and lacks the ability to survive for long periods outside of a human host, specialized handling and precise incubation environments are required for successful isolation.

Cultivating this pathogen is a critical step in diagnosing invasive infections. The choice of medium is significant because Neisseria species are considered fastidious organisms, meaning they have complex nutritional requirements that standard nutrient agars cannot meet. Chocolate agar provides these nutrients by heating blood agar to lyse the red blood cells, which releases intracellular factors like hemoglobin and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD, also known as V factor) that are necessary for growth.

During a diagnostic workup, several morphological and biochemical traits are evaluated to confirm the presence of the pathogen:

- Colony Shape: Circular, convex, and well-defined margins.

- Texture: Smooth and butyrous (butter-like) consistency.

- Atmospheric Requirements: Capnophilic, requiring 5–10% CO2 for optimal growth.

- Gram Stain: Identifying the organism as a Gram-negative diplococcus.

Microbiology and Pathogenesis

Neisseria meningitidis is a Gram-negative diplococcus that is a common commensal in the human nasopharynx, carried asymptomatically by approximately 10% of the population. However, in susceptible individuals, the bacteria can breach the mucosal barrier and enter the bloodstream. The primary virulence factor of this pathogen is its polysaccharide capsule, which allows it to evade host immune defenses, specifically phagocytosis. There are at least 12 different serogroups based on this capsule, with types A, B, C, W, X, and Y being the most prevalent causes of invasive disease.

Once in the bloodstream, the bacteria can cause a systemic inflammatory response known as meningococcemia. The release of lipooligosaccharide (LOS), a potent endotoxin found in the bacterial outer membrane, triggers a massive release of cytokines. This lead to vascular damage, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and multi-organ failure. If the bacteria cross the blood-brain barrier, they infect the meninges, leading to the clinical condition known as bacterial meningitis.

Clinical Significance and Prevention

The clinical presentation of meningococcal disease is often sudden and severe. Patients may present with high fever, a stiff neck (nuchal rigidity), photophobia, and an altered mental state. A hallmark sign is the appearance of a non-blanching petechial or purpuric rash, which indicates underlying vascular damage and systemic involvement. Because the disease can be fatal within 24 to 48 hours of symptom onset, immediate empirical antibiotic treatment is required before laboratory confirmation is even completed.

Prevention strategies primarily focus on vaccination and post-exposure prophylaxis. Meningococcal vaccines target specific serogroups to provide long-term immunity, particularly in high-risk populations such as adolescents, college students, and travelers to endemic areas. In laboratory settings, the visualization of colonies on agar plates, as seen in the provided image, remains a gold-standard technique for confirming a diagnosis and performing antibiotic susceptibility testing to ensure effective treatment.

Effective management of Neisseria meningitidis requires a combination of rapid diagnostic identification, aggressive clinical intervention, and robust public health surveillance. The ability to recognize these specific colonies in a laboratory setting is the first line of defense in identifying outbreaks and preventing the spread of this life-threatening pathogen.