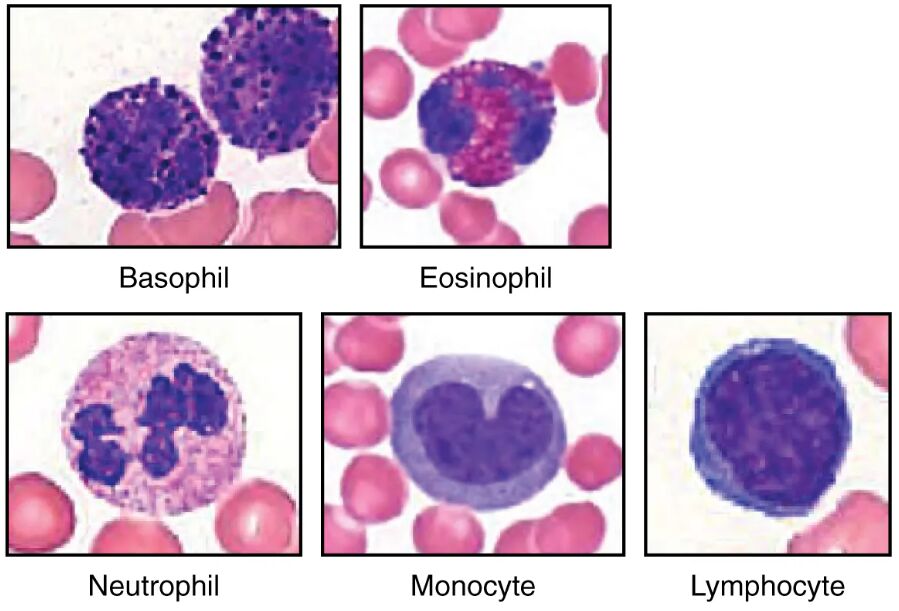

Leukocytes, or white blood cells, are the body’s frontline defenders against infection and disease, and their microscopic appearance provides critical insights into immune function. This image, courtesy of micrographs provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012, showcases various leukocyte types, revealing their unique nuclear and cytoplasmic features under magnification. Examining these cells through detailed imagery enhances understanding of their roles in maintaining health and combating pathogens.

Key Components of Leukocytes Under the Microscope

The image highlights distinct leukocyte types based on their microscopic characteristics.

Neutrophil:

The neutrophil displays a multi-lobed nucleus, typically with two to five segments, and contains small, light lilac-staining granules in its cytoplasm. It is the most abundant leukocyte, rapidly responding to bacterial infections through phagocytosis and releasing antimicrobial agents.

Eosinophil:

The eosinophil is identifiable by its two to three-lobed nucleus and larger, reddish-orange granules that dominate its cytoplasm, indicating its role in parasitic defense. It modulates allergic responses and releases cytotoxic proteins to combat specific pathogens.

Basophil:

The basophil features a two-lobed nucleus often obscured by large, dark blue to purple granules, reflecting its involvement in allergic reactions. It releases histamine and heparin to promote inflammation and prevent excessive clotting during immune responses.

Lymphocyte:

The lymphocyte has a large, round nucleus that occupies most of its cell volume, with a thin rim of pale cytoplasm, suggesting its role in adaptive immunity. It includes subtypes like T and B cells, which are critical for long-term immune memory and antibody production.

Monocyte:

The monocyte is the largest leukocyte, characterized by an indented or horseshoe-shaped nucleus and a grayish-blue cytoplasm, indicating its phagocytic potential. It differentiates into macrophages or dendritic cells in tissues, enhancing immune surveillance and antigen presentation.

The Anatomical and Physiological Role of Leukocytes

Leukocytes are diverse immune cells, each with specialized functions observable under the microscope, playing a pivotal role in protecting the body. The neutrophil, with its multi-lobed nucleus and light granules, is a rapid responder to bacterial invasions, engulfing pathogens and forming pus as part of the innate immune response. Eosinophils, with their vivid granules, target parasites and mitigate allergic reactions, releasing substances like major basic protein to disrupt pathogen membranes.

Basophils, despite their scarcity, are key players in hypersensitivity, with dark granules storing mediators like histamine that trigger vasodilation during allergies. Lymphocytes, with their prominent nuclei, orchestrate adaptive immunity, with T cells attacking infected cells and B cells producing antibodies, influenced by cytokines and indirectly by thyroid hormones like T3 and T4 that regulate metabolism. Monocytes, with their unique nuclear shape, evolve into tissue macrophages, clearing debris and presenting antigens to activate other immune cells.

- Neutrophil Action: Releases neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) to immobilize bacteria; lifespan is short, lasting hours to days.

- Eosinophil Defense: Increases in parasitic infections like schistosomiasis; granules contain peroxidase for oxidative damage.

- Lymphocyte Specificity: T cells require thymic maturation; B cells differentiate into plasma cells upon activation.

- Monocyte Versatility: Macrophages phagocytize apoptotic cells; dendritic cells initiate T-cell responses.

Physical Characteristics and Clinical Relevance

The physical appearance of leukocytes under the microscope provides a window into their function and health status. Neutrophils show segmented nuclei and sparse granules, reflecting their phagocytic readiness, while eosinophils’ larger, colorful granules signal their parasitic focus. Basophils’ dense granules obscure their nuclei, indicating their role in immediate allergic responses, and lymphocytes’ large nuclei suggest their reliance on genetic material for immunity. Monocytes’ indented nuclei and ample cytoplasm highlight their adaptability into larger phagocytic cells.

Clinically, these microscopic features guide diagnosis and treatment. Elevated neutrophil counts may indicate bacterial infection, assessed via complete blood count (CBC) with differential, while increased eosinophils suggest allergies or parasitic infections. High basophil levels can point to chronic allergic conditions, and abnormal lymphocyte or monocyte counts may signal leukemia or chronic inflammation. Flow cytometry and blood smears are used to evaluate these cells, with treatments ranging from antibiotics to immunosuppressive therapy.

- Diagnostic Methods: Differential counts identify leukocyte proportions; Wright’s stain enhances granule visibility.

- Therapeutic Strategies: Corticosteroids reduce eosinophil activity in asthma; G-CSF boosts neutrophil production in neutropenia.

Conclusion

The leukocytes under the microscope image offers a fascinating glimpse into the diverse world of white blood cells, each with distinct features that support immune defense. From neutrophils tackling bacterial threats to lymphocytes shaping long-term immunity, these cells exemplify the body’s protective mechanisms. By studying their microscopic characteristics, one can better appreciate the diagnostic tools and treatments that maintain immune balance, underscoring their vital role in health and disease management.