Legionella pneumophila is a distinctive Gram-negative bacterium primarily known as the causative agent of Legionnaires’ disease, a severe and potentially fatal form of pneumonia. Thriving in warm aquatic environments, this pathogen poses a significant risk to public health when aerosolized through man-made water systems such as cooling towers, hot tubs, and large-scale plumbing. Understanding the morphology, environmental niche, and pathogenesis of this organism is crucial for effective prevention, rapid diagnosis, and successful clinical intervention.

The organism Legionella pneumophila is a facultative intracellular parasite that has evolved unique mechanisms to survive both in the environment and within a human host. In nature, it often resides within biofilms or as an endosymbiont inside freshwater amoebae, which provide protection from harsh conditions and chemical disinfectants. This environmental resilience allows the bacteria to colonize complex water distribution systems where temperatures range between 20°C and 50°C, providing an ideal thermal niche for proliferation.

Transmission to humans occurs exclusively through the inhalation of contaminated aerosols or, more rarely, through the aspiration of contaminated water. It is important to note that Legionella is not typically spread through person-to-person contact, making environmental water management the primary focus of public health prevention. Once the bacteria reach the lower respiratory tract, they are engulfed by alveolar macrophages, where they cleverly bypass the host’s immune defenses to replicate within specialized vacuoles.

Key biological and environmental characteristics of Legionella pneumophila include:

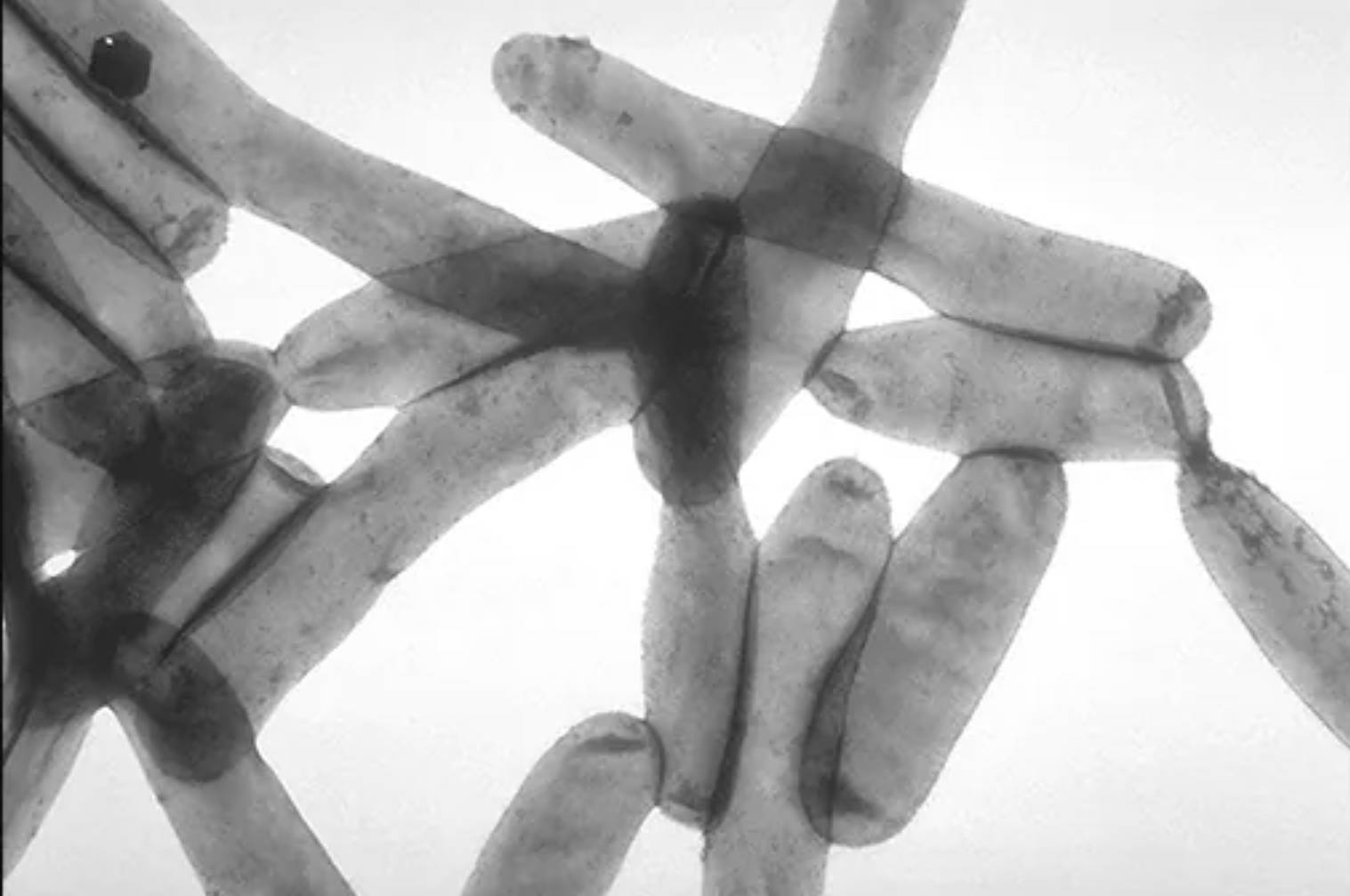

- Morphology: Pleomorphic, Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria as seen in electron microscopy.

- Nutritional Requirements: Fastidious growth, requiring L-cysteine and iron-enriched media like Buffered Charcoal Yeast Extract (BCYE) agar.

- Movement: Many strains possess a single polar flagellum that aids in motility and host cell attachment.

- Niche: Preference for warm, stagnant water and protection within complex microbial biofilms.

Understanding Legionnaires’ Disease and Pontiac Fever

Infection with Legionella species can lead to two distinct clinical syndromes, collectively referred to as legionellosis. The more severe form, Legionnaires’ disease, presents as a multi-system illness dominated by severe pneumonia. Symptoms typically begin two to ten days after exposure and include high fever, cough, shortness of breath, muscle aches, and headaches. A unique clinical feature often associated with this infection is gastrointestinal involvement, such as diarrhea, and neurological symptoms like confusion or ataxia.

The second, milder form of the infection is known as Pontiac fever. Unlike its more dangerous counterpart, this condition is a self-limiting, flu-like illness that does not involve the lungs. Patients typically recover within a few days without the need for antibiotic therapy. While the exact reason for the difference in severity between the two syndromes is not fully understood, it is believed to involve the dose of the bacterial inoculum and the underlying health status of the host’s immune system.

Risk Factors and Pathophysiological Impact

The risk of developing a severe pulmonary infection is significantly higher in certain populations. Individuals over the age of 50, current or former smokers, and those with chronic lung diseases such as COPD are at the highest risk. Furthermore, immunocompromised individuals, including those with cancer or those undergoing organ transplants, are particularly vulnerable to the systemic inflammatory response triggered by the bacteria’s lipopolysaccharide (LPS) endotoxins.

If left untreated, this form of atypical pneumonia can lead to respiratory failure, septic shock, and acute renal failure. The bacteria’s ability to manipulate host cell signaling allows it to prevent the fusion of lysosomes with the phagosomes they inhabit, effectively turning the immune cells intended to destroy them into “nurseries” for bacterial replication. This intracellular lifestyle is a hallmark of the pathogen’s virulence and makes it difficult for some standard antibiotics to reach the target organism.

Diagnosis and Modern Treatment Strategies

Clinical diagnosis relies on a combination of patient history, radiographic imaging showing pulmonary infiltrates, and laboratory testing. The urinary antigen test is a common rapid diagnostic tool, though it primarily detects L. pneumophila serogroup 1. For a definitive diagnosis, culture of respiratory secretions on specialized agar or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is utilized to identify the specific strain and guide treatment.

Because the bacteria reside inside host cells, the preferred treatment involves antibiotics with high intracellular penetration. Macrolides, such as azithromycin, and respiratory fluoroquinolones, such as levofloxacin, are the gold standards for treating atypical pneumonia caused by this pathogen. Early administration of these medications is vital for improving patient outcomes and reducing the mortality rate, which can reach up to 10% in communal cases and higher in healthcare-associated outbreaks.

Advancements in environmental microbiology and public health engineering continue to improve our ability to detect Legionella in water systems before human exposure occurs. By maintaining strict water temperature controls and utilizing effective biocide treatments, facilities can mitigate the growth of these rod-shaped pathogens. Continued vigilance in both clinical settings and environmental management remains the most effective way to combat the persistent threat of legionellosis.