This article explores the intricate pressure dynamics within the thoracic cavity, essential for understanding how we breathe. We’ll delve into the specific roles of intrapulmonary and intrapleural pressures, along with transpulmonary pressure, to illuminate the mechanics of ventilation. Gain a clearer understanding of these vital physiological processes that drive every breath you take.

Atmospheric pressure: This refers to the pressure exerted by the air surrounding the body. It is a critical external force that influences the movement of air into and out of the lungs during respiration. In a medical context, it serves as a baseline against which other thoracic pressures are measured.

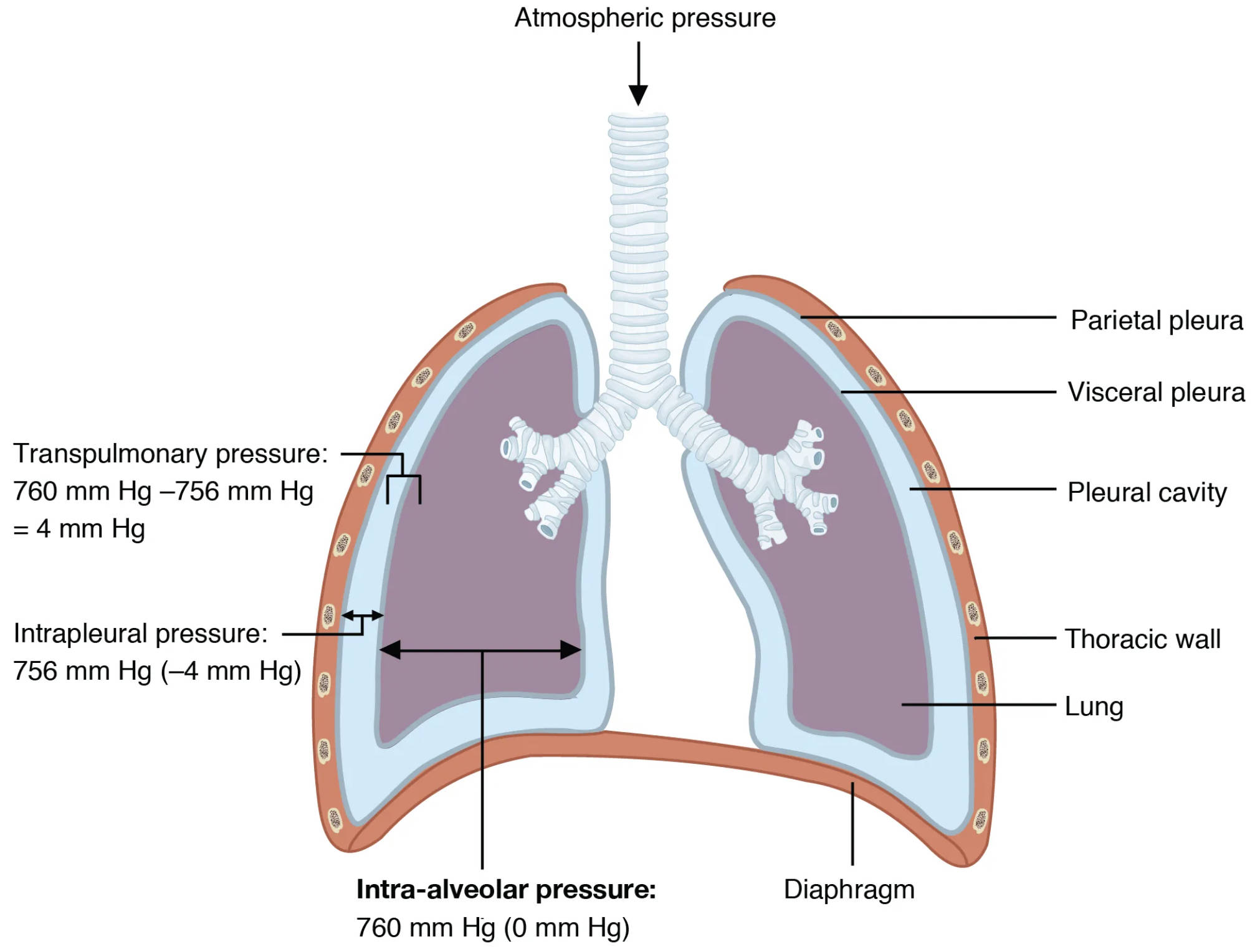

Parietal pleura: This is the outer layer of the serous membrane that lines the thoracic cavity. It is attached to the inner surface of the ribs and the superior surface of the diaphragm, forming a protective barrier. This layer plays a crucial role in maintaining the intrapleural pressure that is vital for lung expansion.

Visceral pleura: This is the inner layer of the serous membrane that directly covers the surface of the lungs. It extends into the fissures between the lung lobes, creating a smooth, slippery surface. Its close adherence to the lung tissue allows the lungs to move freely within the thoracic cavity during breathing.

Pleural cavity: This is the potential space located between the parietal and visceral pleura. It contains a thin layer of lubricating pleural fluid, which reduces friction as the lungs expand and contract. The unique pressure within this cavity is fundamental to the mechanism of pulmonary ventilation.

Transpulmonary pressure: 760 mm Hg – 756 mm Hg = 4 mm Hg: This represents the difference between the intra-alveolar pressure and the intrapleural pressure. It is a critical measure that dictates the size of the lungs. A positive transpulmonary pressure is always necessary to keep the lungs inflated and prevent their collapse.

Intrapleural pressure: 756 mm Hg (-4 mm Hg): This is the pressure within the pleural cavity. It is always lower than the atmospheric pressure and usually lower than the intra-alveolar pressure, creating a suction effect that keeps the lungs expanded. This negative pressure is crucial for preventing atelectasis, or lung collapse.

Thoracic wall: This anatomical structure forms the protective cage around the lungs and heart. Comprising the ribs, sternum, and thoracic vertebrae, it provides a rigid yet flexible framework. The expansion and contraction of the thoracic wall, driven by respiratory muscles, directly impact intrapleural and intrapulmonary pressures.

Lung: These are the primary organs of respiration, responsible for gas exchange. They are elastic structures that expand and recoil with each breath. Their ability to inflate and deflate depends entirely on the intricate pressure gradients maintained within the thoracic cavity.

Intra-alveolar pressure: 760 mm Hg (0 mm Hg): Also known as intrapulmonary pressure, this is the pressure within the alveoli of the lungs. It fluctuates during the respiratory cycle, becoming negative during inspiration to draw air in and positive during expiration to push air out. At rest, it equalizes with atmospheric pressure.

Diaphragm: This is a large, dome-shaped muscle located at the base of the thoracic cavity. It is the primary muscle of inspiration, contracting and flattening to increase the volume of the thoracic cavity. Its coordinated movement is essential for establishing the pressure changes required for breathing.

Respiration, the fundamental process of breathing, relies on precise pressure changes within the thoracic cavity. The image above illustrates the critical relationships between intrapulmonary and intrapleural pressures, which are essential for effective ventilation. Understanding these pressure dynamics is key to comprehending how air moves into and out of our lungs, enabling the vital exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide. These pressures are not static; they fluctuate throughout the respiratory cycle, driven by muscle contractions and the elastic properties of the lungs and thoracic wall.

The process begins with the concept of atmospheric pressure, the external force exerted by the air around us. For air to enter the lungs during inspiration, the pressure inside the lungs (intra-alveolar pressure) must become lower than atmospheric pressure. Conversely, for air to leave the lungs during expiration, the intra-alveolar pressure must become higher than atmospheric pressure. This creation of pressure gradients is meticulously orchestrated by changes in the volume of the thoracic cavity, primarily mediated by the diaphragm and intercostal muscles.

Crucially, the intrapleural pressure, the pressure within the pleural cavity, remains consistently negative relative to both atmospheric and intra-alveolar pressures. This negative pressure acts like a suction, pulling the visceral pleura (lining the lungs) towards the parietal pleura (lining the thoracic wall), thereby keeping the lungs inflated. The difference between the intra-alveolar pressure and the intrapleural pressure is known as transpulmonary pressure. A positive transpulmonary pressure ensures the lungs remain expanded and do not collapse, highlighting its vital role in preventing conditions like atelectasis.

The delicate balance and precise changes in these pressures are paramount for healthy respiratory function. Any disruption to this system, such as a breach in the pleural cavity leading to a pneumothorax, can significantly impair the ability of the lungs to inflate, demonstrating the profound physiological importance of these pressure relationships. The constant interplay between atmospheric, intra-alveolar, and intrapleural pressures ensures that the rhythmic act of breathing proceeds smoothly, sustaining life.

In summary, the intricate dance of intrapulmonary and intrapleural pressures, alongside atmospheric pressure, forms the bedrock of pulmonary ventilation. Each component, from the pleural layers to the diaphragm, plays a specific role in creating and maintaining the pressure gradients necessary for air movement. A thorough understanding of these relationships is indispensable for anyone studying respiratory physiology, as it illuminates the elegant mechanics behind every breath we take.