Immunofluorescence is a vital laboratory technique that utilizes antibody-antigen interactions to visualize specific microscopic structures within biological samples. By tagging antibodies with fluorescent dyes, clinicians can detect the presence of pathogens, such as bacteria and parasites, with high specificity and sensitivity. This article explores the mechanisms of direct and indirect immunofluorescence, illustrating their clinical application in diagnosing conditions like gonorrhea and schistosomiasis.

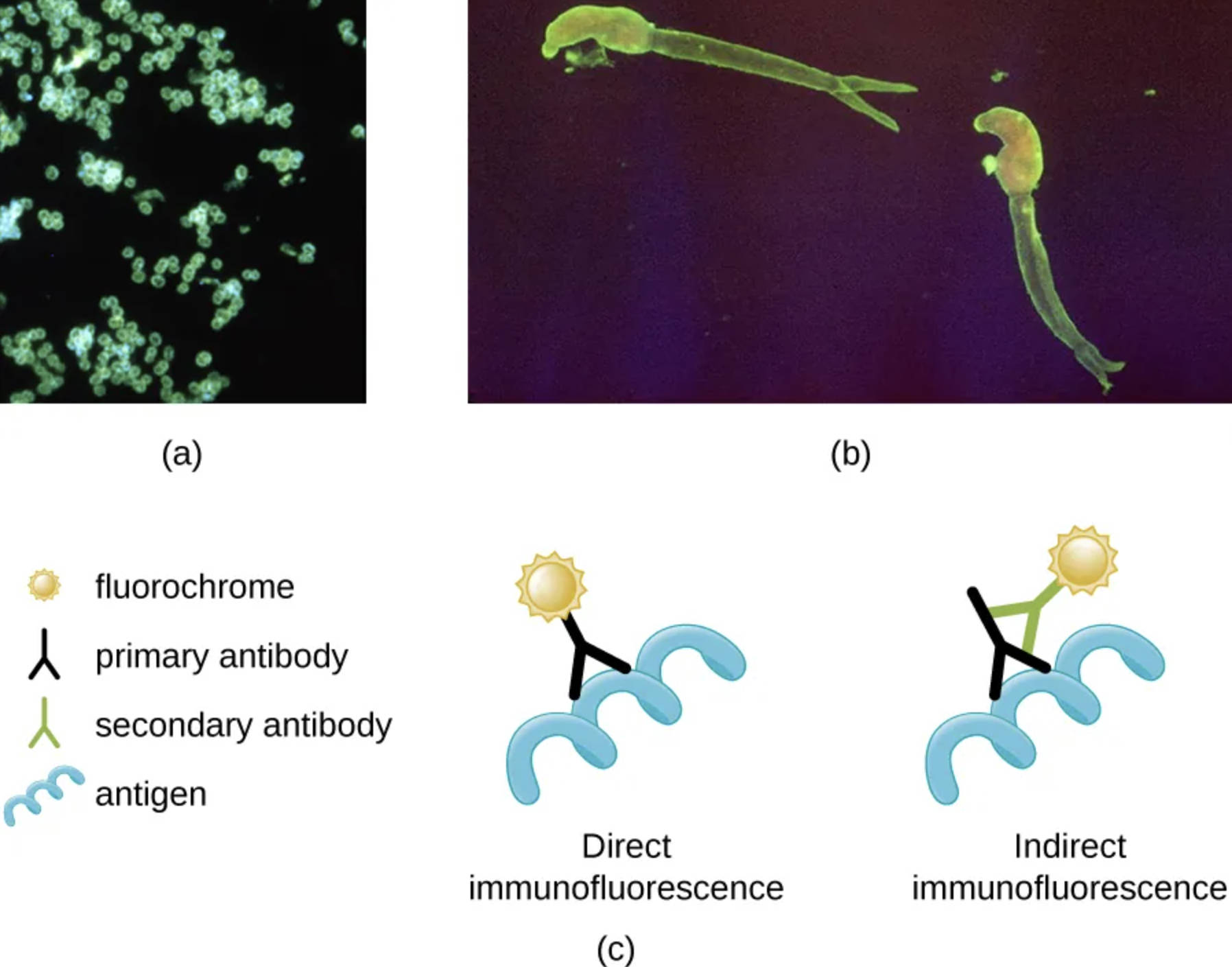

Neisseria gonorrhoeae (a): This panel demonstrates a positive direct immunofluorescent stain identifying the bacterium responsible for gonorrhea. The glowing green clusters indicate where the fluorescently labeled primary antibodies have successfully bound directly to the antigens on the surface of the bacteria.

Schistosoma mansoni (b): This panel reveals the larvae of a parasitic blood fluke visualized through indirect immunofluorescence. Here, the glowing outline is the result of a two-step process where a secondary antibody carrying the fluorochrome binds to an unlabeled primary antibody that is attached to the parasite.

Direct Immunofluorescence (c): In this schematic representation, the staining process involves a single step where a primary antibody is chemically conjugated with a fluorochrome. This labeled antibody reacts directly with the specific antigen on the pathogen, providing a quick but sometimes less sensitive diagnostic result.

Indirect Immunofluorescence (c): This diagram illustrates a two-step method where the primary antibody is unlabeled and binds to the antigen first. Subsequently, a fluorochrome-labeled secondary antibody, which is specific to the primary antibody, is introduced to visualize the complex, often resulting in signal amplification.

Fluorochrome: Represented by the sun-like icon, this is a fluorescent chemical compound that can re-emit light upon light excitation. In diagnostic imaging, these dyes (such as fluorescein isothiocyanate) are attached to antibodies to make invisible microscopic targets glow under ultraviolet light.

Primary Antibody: This Y-shaped protein is designed to specifically recognize and bind to a unique antigen found on the pathogen. In direct methods, it carries the dye, whereas, in indirect methods, it serves as a bridge between the antigen and the secondary antibody.

Secondary Antibody: Used exclusively in the indirect method, this antibody binds to the constant region of the primary antibody. Because multiple secondary antibodies can bind to a single primary antibody, this significantly increases the brightness of the fluorescence, enhancing the test’s sensitivity.

Antigen: Illustrated as a blue helical structure, the antigen represents a specific molecule or surface protein on the pathogen, such as a bacterium or virus. The entire premise of immunofluorescent testing relies on the precise “lock and key” fit between this antigen and the primary antibody.

Principles of Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Immunofluorescence microscopy combines the precision of immunology with the resolution of microscopy to identify pathogens that may be difficult to culture or see with standard staining methods. The technique hinges on the specificity of antibodies—proteins produced by the immune system—to bind to specific foreign substances known as antigens. When these antibodies are tagged with a fluorochrome, they illuminate the target organism against a dark background, creating a high-contrast image that is easily interpreted by pathologists.

There are two primary variations of this technique: direct and indirect. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) is favored for its speed and simplicity, as it requires only one incubation step. It is commonly used to detect antigens in tissue biopsies or fresh clinical specimens. However, indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) is often preferred for its superior sensitivity. Because multiple labeled secondary antibodies can attach to a single primary antibody, the fluorescent signal is amplified, making it easier to detect pathogens present in low numbers.

The clinical utility of these techniques extends across various fields of medicine, from diagnosing autoimmune blistering diseases to identifying infectious agents. The choice between direct and indirect methods depends on the specific clinical question, the type of sample available, and the urgency of the diagnosis.

Key advantages of immunofluorescence techniques include:

- High Specificity: The antibody-antigen bond ensures that only the target pathogen is visualized.

- Rapid Diagnosis: Results can often be obtained much faster than traditional culture methods.

- Signal Amplification: Indirect methods allow for the detection of low-concentration antigens.

- Localization: It allows researchers to see exactly where an antigen is located within a cell or tissue.

Clinical Application: Gonorrhea and Neisseria gonorrhoeae

The image provided in panel (a) highlights the detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, the causative agent of gonorrhea. Gonorrhea is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) that primarily affects the mucous membranes of the reproductive tract, including the cervix, uterus, and fallopian tubes in women, and the urethra in women and men. It can also infect the mucous membranes of the mouth, throat, eyes, and rectum.

The bacterium N. gonorrhoeae is a Gram-negative diplococcus, meaning it typically appears in pairs resembling coffee beans. In a clinical setting, direct immunofluorescence can be used to rapidly identify these bacteria in urethral or cervical smears. This is crucial because untreated gonorrhea can lead to severe complications. In women, it is a leading cause of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which can result in tubal infertility or ectopic pregnancy. In men, it can cause epididymitis. Furthermore, disseminated gonococcal infection can occur if the bacteria enter the bloodstream, leading to arthritis, dermatitis, and tenosynovitis.

Clinical Application: Schistosomiasis and Schistosoma mansoni

Panel (b) illustrates the utility of indirect immunofluorescence in detecting Schistosoma mansoni, a parasitic trematode (fluke) responsible for intestinal schistosomiasis. This neglected tropical disease affects millions of people worldwide, particularly in Africa, the Caribbean, and South America. Infection occurs when humans come into contact with freshwater contaminated by certain snails that carry the parasite. The microscopic larvae (cercariae) penetrate the human skin, migrate through the bloodstream, and eventually mature into adult worms in the blood vessels of the liver and intestine.

The pathology of schistosomiasis is largely driven by the host’s immune response to the parasite’s eggs, which can become trapped in tissues. This chronic inflammation can lead to intestinal damage, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and blood in the stool. Over time, the eggs trapped in the liver can cause periportal fibrosis, leading to portal hypertension, splenomegaly (enlarged spleen), and variceal bleeding. Indirect immunofluorescence is particularly valuable here; rather than finding the worm itself, the test often detects antibodies in the patient’s blood that react with schistosome antigens, indicating current or past infection. This serological approach is essential for screening populations in endemic areas where direct egg detection in stool might be less sensitive in light infections.

Conclusion

The distinction between direct and indirect immunofluorescence is fundamental to modern clinical diagnostics. Whether identifying the swift replication of bacterial pathogens like Neisseria gonorrhoeae or screening for the complex immune response provoked by parasites like Schistosoma mansoni, these techniques provide the visual evidence necessary for accurate treatment. By illuminating the unseen, immunofluorescence remains an indispensable tool in the fight against infectious diseases.