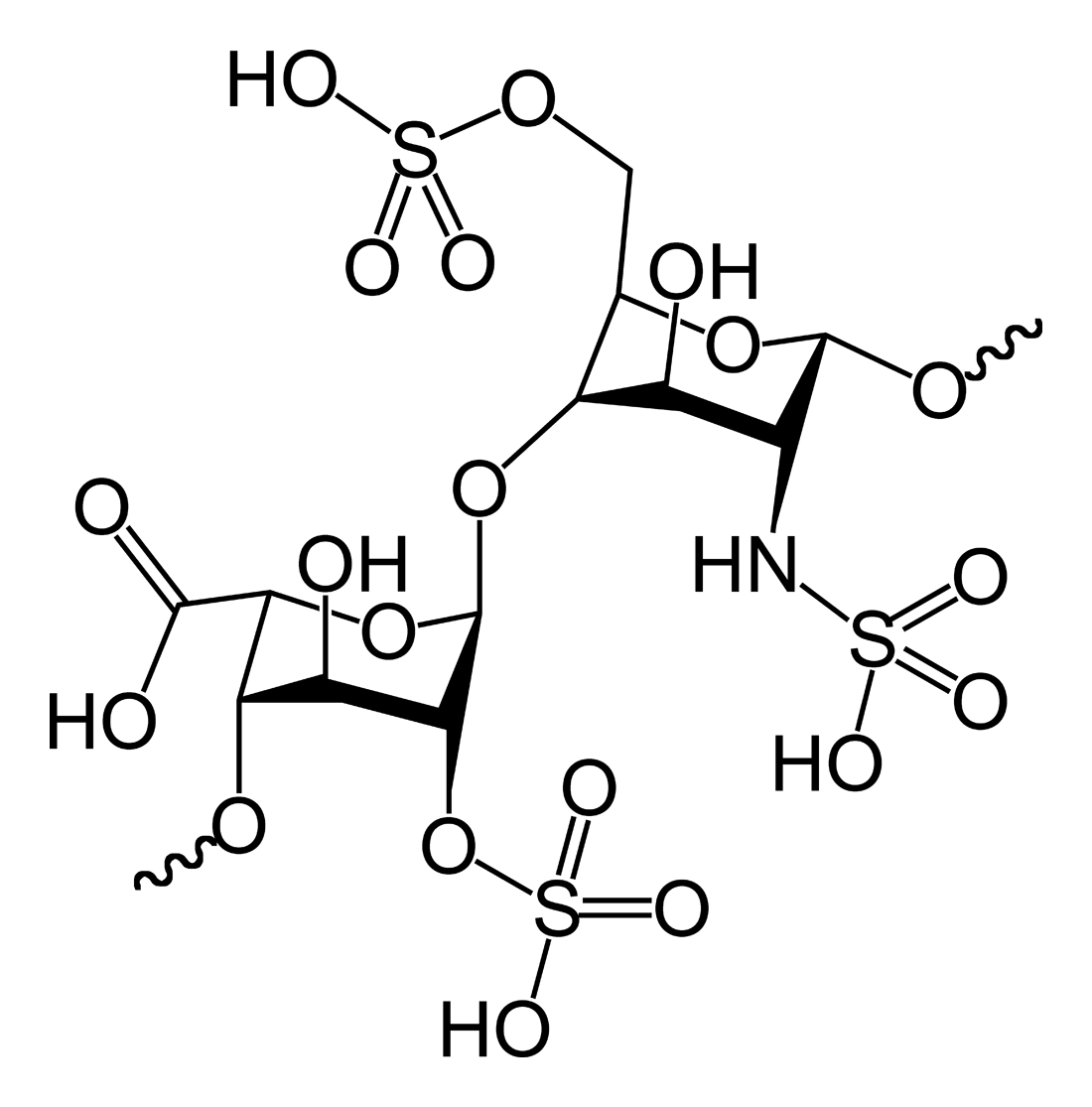

Heparin is a naturally occurring glycosaminoglycan that serves as a potent anticoagulant, widely used in modern medicine to prevent and treat the formation of blood clots. This article explores the detailed chemical structure of heparin as depicted in the diagram, analyzing how its highly sulfated polysaccharide chain enables it to interact with the body’s coagulation system to inhibit thrombosis and maintain hemostasis.

Chemical Components of the Heparin Molecule

Sulfate Groups:

The diagram features multiple sulfate groups (represented as -OSO3H and -NHSO3H) attached to the sugar rings. These groups are responsible for heparin’s highly negative electric charge, which is the strongest of any biological molecule found in the human body and is crucial for its high-affinity binding to antithrombin III.

Carboxyl Groups:

Visible on the left sugar ring (iduronic acid), the carboxyl group (-COOH) contributes to the molecule’s polarity and solubility in water. This acidic group, along with the sulfates, enhances the molecule’s ability to interact with positively charged amino acid residues on coagulation factors.

Pyranose Rings:

The central structure consists of six-membered sugar rings, specifically derivatives of glucosamine and iduronic acid. These rings form the backbone of the polymer chain, providing the structural scaffold necessary to present the active chemical groups to their biological targets in a specific orientation.

Glycosidic Bond:

Connecting the two sugar rings is an oxygen bridge known as a glycosidic bond. This linkage allows for the polymerization of disaccharide units into long, linear chains, creating the varying lengths of polysaccharide molecules found in unfractionated heparin.

Amine Group:

On the glucosamine residue (right side), a nitrogen atom is attached to the ring, forming part of a sulfamido group (-NH-). This modification distinguishes glucosamine from simple glucose and is a key structural feature that enzymes recognize during the biosynthesis and degradation of heparin.

Introduction to Heparin and Glycosaminoglycans

Heparin is classified as a glycosaminoglycan (GAG), a complex carbohydrate composed of repeating disaccharide units. While it is best known as a pharmaceutical drug, it is also synthesized endogenously by mast cells and basophils within the human body. The image above illustrates a specific disaccharide fragment of the heparin chain, highlighting the 2-O-sulfated iduronic acid and 6-O-sulfated, N-sulfated glucosamine. This specific pattern of sulfation is not random; it is synthesized by a series of enzymes in the Golgi apparatus, resulting in a molecule with a high charge density that dictates its biological activity.

In a clinical setting, heparin is indispensable for the management of hemostatic disorders. It does not dissolve existing clots but rather prevents the formation of new ones and stops existing clots from expanding. This allows the body’s natural fibrinolytic mechanisms to break down the clot over time. The structural complexity shown in the 2D skeletal diagram explains why heparin must be administered parenterally (via injection or IV); its large size and negative charge prevent it from being absorbed through the gut lining if taken orally.

Understanding the molecular architecture of heparin is vital for comprehending its pharmacodynamics. The specific sequence of five sugar units (a pentasaccharide sequence) containing the unique sulfation pattern shown is required to bind and activate antithrombin. Without this specific chemical arrangement, the drug would fail to accelerate the inhibition of clotting factors.

Key characteristics of Heparin include:

- High Acidity: Due to the abundance of sulfate and carboxyl groups.

- Rapid Onset: When administered intravenously, it acts almost immediately.

- Biological Source: Often derived from porcine intestinal mucosa or bovine lung tissue.

- Reversibility: Its effects can be neutralized by protamine sulfate, a positively charged protein that binds to the negative heparin molecule.

The Physiology of Anticoagulation and Thrombosis

The primary physiological role of heparin relies on its ability to potentiate the activity of Antithrombin III, a naturally occurring plasma protein. Under normal conditions, Antithrombin III inhibits coagulation enzymes at a slow rate. However, when heparin enters the bloodstream, it binds to Antithrombin III, inducing a conformational change in the protein. This change exposes the active site of Antithrombin III, accelerating its ability to inactivate Thrombin (Factor IIa) and Factor Xa by up to 1,000-fold.

The chemical structure is paramount to this mechanism. The negatively charged sulfate groups on the heparin chain interact electrostatically with the positively charged lysine and arginine residues on Antithrombin III. Once the Antithrombin-Clotting Factor complex is formed, heparin releases from the molecule and is free to bind to another Antithrombin III molecule, effectively acting as a catalyst. This mechanism effectively halts the coagulation cascade, preventing the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin, which is the structural mesh that forms blood clots.

This physiological interaction is critical in treating conditions such as Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) and Pulmonary Embolism (PE). In these disease states, blood flow is sluggish or the vessel wall is damaged, triggering inappropriate clotting. By inhibiting Factor Xa and Thrombin, heparin prevents the propagation of the thrombus. Because heparin acts on multiple points in the coagulation cascade, its therapeutic range must be carefully monitored, typically using the activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (aPTT) test, to ensure the blood is sufficiently anticoagulated without causing excessive bleeding.

Conclusion

The 2D skeletal structure of heparin reveals a sophisticated molecular design perfectly evolved for its role in hemostasis. The arrangement of sulfate and carboxyl groups on the sugar backbone provides the electrochemical properties necessary to act as a high-affinity ligand for antithrombin. By deciphering this chemical structure, medical science has been able to harness heparin as a life-saving therapy for millions of patients suffering from thrombotic disorders, bridging the gap between basic biochemistry and critical care medicine.