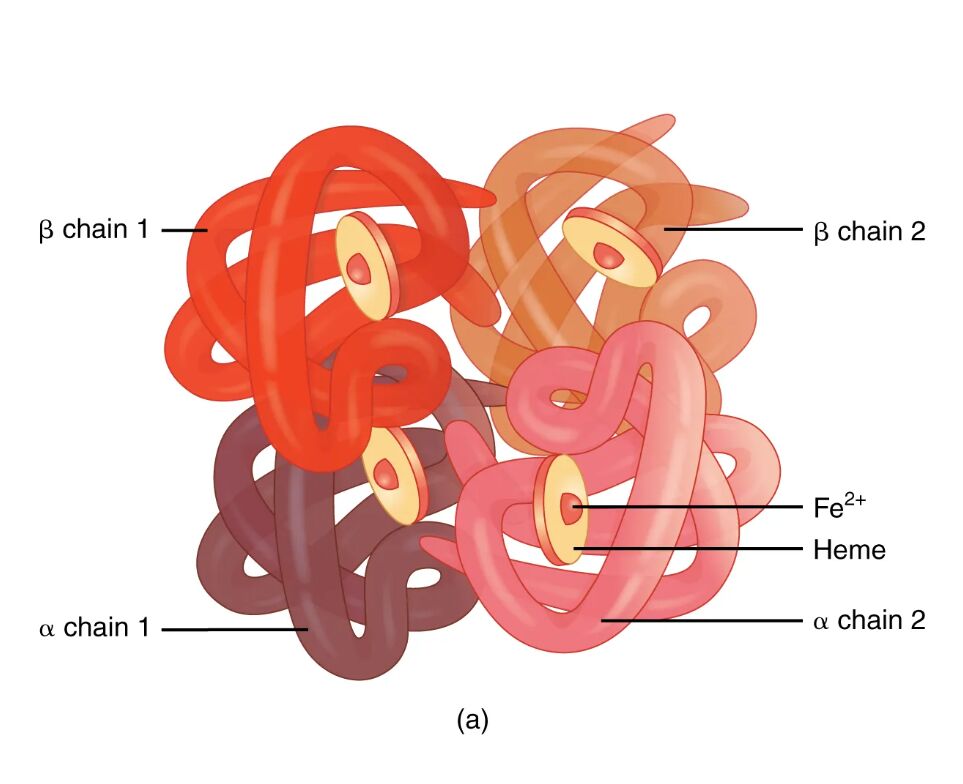

Hemoglobin is the oxygen-carrying protein essential for sustaining life, found within red blood cells and composed of four globin proteins intricately linked to heme groups. This diagram vividly illustrates the hemoglobin molecule’s quaternary structure, showcasing the arrangement of its alpha and beta chains, which work together to transport oxygen efficiently. Exploring this structure deepens the understanding of its critical role in respiration and overall physiological balance.

Key Components of the Hemoglobin Molecule

The diagram highlights the specific parts that make up the hemoglobin structure.

α chain 1:

This alpha globin chain forms one of the two identical subunits in the hemoglobin tetramer, providing structural support and oxygen-binding sites. It pairs with a heme group, enabling the molecule to capture and release oxygen as needed by tissues.

α chain 2:

The second alpha globin chain complements α chain 1, contributing to the symmetrical stability of the hemoglobin molecule. Together with the beta chains, it facilitates the cooperative binding of oxygen molecules.

β chain 1:

This beta globin chain is one of two that pair with the alpha chains, playing a key role in modulating oxygen affinity through allosteric changes. It binds a heme group, essential for the protein’s gas exchange function.

β chain 2:

The second beta globin chain mirrors β chain 1, enhancing the hemoglobin’s ability to adapt to varying oxygen levels in the body. Its interaction with alpha chains ensures efficient oxygen delivery and carbon dioxide transport.

Heme:

Heme is the iron-containing pigment bound to each globin chain, containing a ferrous iron (Fe²⁺) ion that reversibly binds oxygen. This component is crucial for hemoglobin’s primary function of oxygen transport and its secondary role in carbon dioxide carriage.

Fe²⁺:

The ferrous iron ion within the heme group serves as the binding site for oxygen, undergoing conformational shifts that enhance additional oxygen uptake. Its reduced state is vital for maintaining hemoglobin’s oxygen-carrying capacity.

The Anatomical and Physiological Role of Hemoglobin

Hemoglobin’s structure is a sophisticated assembly that enables red blood cells to deliver oxygen from the lungs to tissues and return carbon dioxide for exhalation. The tetramer, consisting of two α chains and two β chains, each associated with a heme group, exhibits cooperative binding, where the attachment of one oxygen molecule increases affinity for others. This allosteric regulation, influenced by pH and carbon dioxide via the Bohr effect, ensures oxygen release in metabolically active areas like muscles.

The Fe²⁺ ion within heme forms a reversible bond with oxygen, a process supported by the globin chains’ hydrophobic environment. Hemoglobin also aids in acid-base balance by transporting about 10% of carbon dioxide as carbaminohemoglobin, with the remainder converted to bicarbonate ions. Hormones such as erythropoietin, produced by the kidneys in response to low oxygen levels, stimulate red blood cell production to maintain adequate hemoglobin levels, influenced indirectly by thyroid hormones like T3 and T4 that regulate metabolic demand.

- Oxygen Delivery: Hemoglobin’s quaternary structure allows up to four oxygen molecules to bind; affinity drops in acidic, high-CO₂ environments.

- Carbon Dioxide Management: Carbaminohemoglobin formation aids CO₂ transport; the chloride shift balances charge during this process.

- Structural Dynamics: Alpha and beta chains are encoded by separate genes; their synthesis is balanced to prevent hemoglobinopathies.

Physical Characteristics and Clinical Relevance

The physical depiction of hemoglobin reveals a compact, globular protein optimized for its role within erythrocytes. The four globin chains, wrapped around heme groups, create a structure that fits approximately 300 million hemoglobin molecules per red blood cell, enabling the transport of over 1 billion oxygen molecules. This high capacity underscores its efficiency in gas exchange.

Clinically, hemoglobin’s structure is a focal point for diagnosing blood disorders. Abnormalities in globin chain production, such as in thalassemia, or mutations like hemoglobin S in sickle cell disease, disrupt oxygen transport. Laboratory techniques, including hemoglobin electrophoresis, identify these variants, guiding treatments like transfusions or hydroxyurea to boost fetal hemoglobin. Regular monitoring of hemoglobin levels via complete blood counts helps assess oxygen-carrying capacity and overall health.

- Diagnostic Methods: Pulse oximetry measures oxygen saturation non-invasively; mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) evaluates individual cell content.

- Therapeutic Strategies: Iron supplementation corrects iron-deficiency anemia; gene therapy is emerging for sickle cell disease management.

Conclusion

The hemoglobin molecule diagram with its four globin proteins offers a window into the intricate mechanism that sustains oxygen delivery and carbon dioxide removal. This structure not only highlights the protein’s adaptability to physiological needs but also serves as a critical diagnostic tool for hematological conditions. By studying its components, one can better appreciate the body’s remarkable ability to maintain homeostasis, emphasizing the importance of preserving hemoglobin function for optimal health.