Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a Gram-negative, spiral-shaped bacterium that colonizes the human stomach. This resilient pathogen is uniquely adapted to survive in highly acidic environments, making it the leading cause of chronic gastritis, most peptic ulcers, and a significant driver of gastric cancer globally.

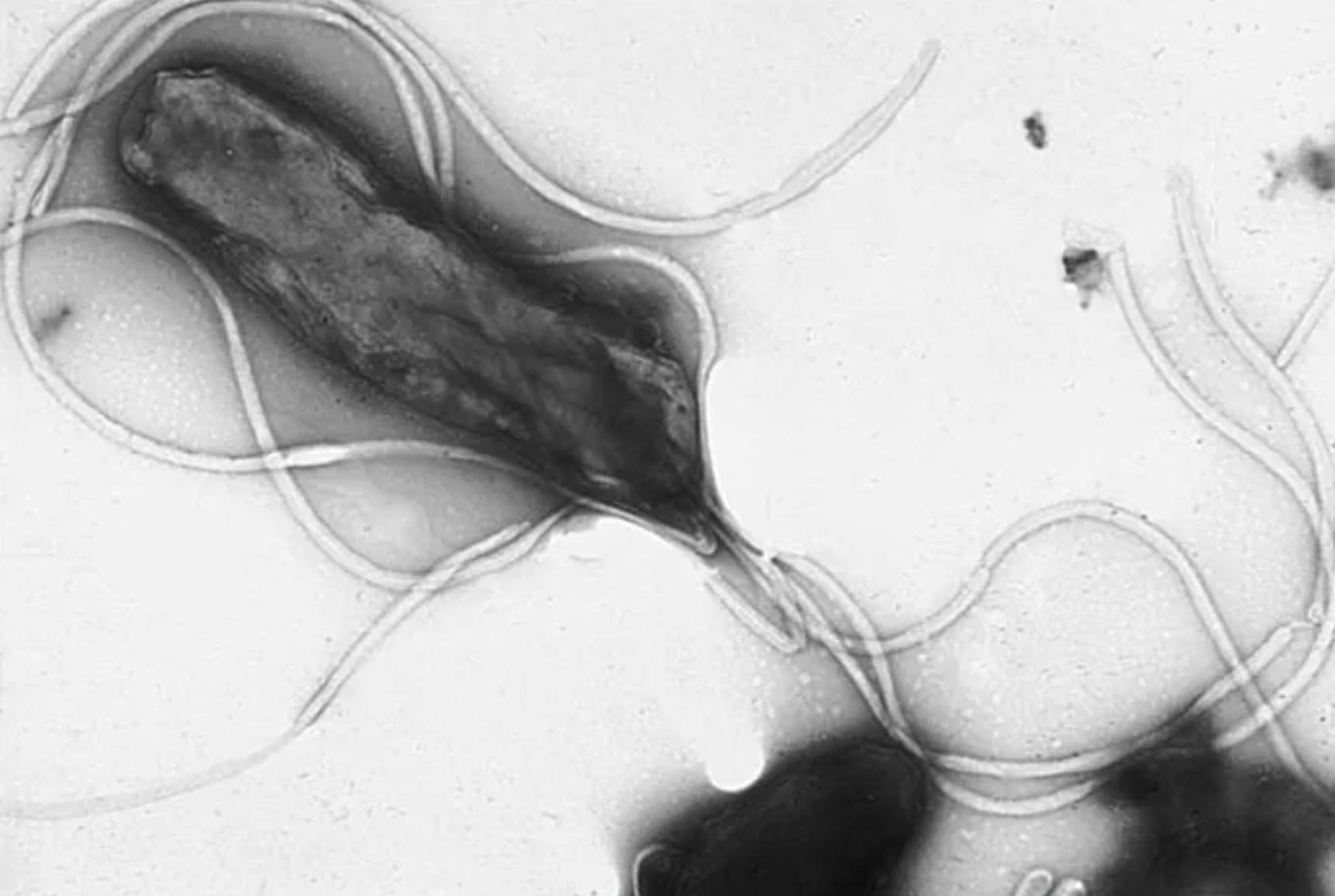

Helicobacter pylori represents a landmark discovery in modern medicine, shifting the clinical understanding of stomach ailments from lifestyle-based factors to an infectious etiology. As a microaerophilic organism, it requires low levels of oxygen to survive and is primarily transmitted through the fecal-oral or oral-oral routes. Once it enters the human digestive tract, the bacterium utilizes its specialized morphology to navigate the treacherous environment of the stomach, where the pH can drop as low as 1.5.

The survival of H. pylori is dependent on its ability to produce the enzyme urease, which catalyzes the hydrolysis of urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide. The resulting ammonia acts as a chemical buffer, neutralizing the gastric acid in the immediate vicinity of the bacterium and creating a “neutral cloud” that allows it to survive. After neutralizing the local environment, the bacterium uses its polar flagella to burrow through the thick mucus layer and attach to the gastric epithelial cells, where it establishes a long-term infection.

The presence of H. pylori triggers a complex immune response that, while unable to clear the infection, leads to persistent tissue damage. The severity of the disease often depends on the virulence factors of the specific strain, such as the CagA (cytotoxin-associated gene A) and VacA (vacuolating cytotoxin) proteins. These factors can alter host cell signaling, leading to cell death and the breakdown of the mucosal barrier.

Key biological traits of Helicobacter pylori include:

- Spiral or helical morphology designed for high-viscosity movement.

- Production of high concentrations of the urease enzyme for acid neutralization.

- Multiple polar flagella that provide rapid motility within the gastric mucus.

- Ability to induce a chronic inflammatory state that persists for decades.

Pathogenesis of Chronic Gastritis and Peptic Ulcer Disease

When H. pylori colonizes the stomach, it initiates a state of chronic gastritis, characterized by the inflammation of the stomach lining. In the early stages, this may be asymptomatic, but as the infection persists, the inflammation disrupts the balance between gastric acid production and mucosal protection. This imbalance frequently leads to peptic ulcer disease, which manifests as painful sores in the lining of the stomach or the duodenum.

Clinically, patients with ulcers often experience a gnawing or burning sensation in the upper abdomen, especially when the stomach is empty. If left untreated, these ulcers can lead to serious complications, including internal bleeding or gastric perforation, where the ulcer creates a hole through the entire wall of the stomach. The discovery that most ulcers are caused by this bacterium has revolutionized treatment, allowing patients to be cured with targeted antibiotic regimens rather than lifelong antacid therapy.

The Link to Gastric Cancer and Oncogenesis

The most severe consequence of long-term H. pylori infection is its strong association with gastric adenocarcinoma and MALT (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue) lymphoma. The World Health Organization classifies H. pylori as a Group 1 carcinogen because the constant cycle of inflammation and cell regeneration increases the likelihood of genetic mutations. Over time, chronic superficial gastritis can progress to atrophic gastritis, where the healthy stomach cells are replaced by fibrous tissue or intestinal-type cells, a process known as intestinal metaplasia.

In virulent strains, the CagA protein is injected directly into the host cells via a type IV secretion system. This protein acts as an oncoprotein, disrupting the normal life cycle of the gastric cells and promoting uncontrolled proliferation. Because stomach cancer is often diagnosed in advanced stages, the early detection and eradication of H. pylori in high-risk populations is considered one of the most effective strategies for cancer prevention.

Diagnostic Procedures and Treatment Protocols

Diagnosis of an active H. pylori infection can be achieved through both non-invasive and invasive methods. Non-invasive options include the urea breath test, where a patient ingests labeled urea and their breath is analyzed for byproduct gases, and the stool antigen test. Invasive diagnosis involves an upper endoscopy, allowing a gastroenterologist to take a tissue biopsy for histological examination or a rapid urease test (CLO test) to confirm the presence of the organism.

Effective treatment typically involves a combination of medications known as “triple therapy” or “quadruple therapy.” These regimens usually include two different antibiotics, such as clarithromycin and amoxicillin, paired with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) to suppress acid production and facilitate healing. Successful eradication not only cures current ulcers but also significantly reduces the lifetime risk of developing gastrointestinal malignancies.

The study of Helicobacter pylori continues to provide deep insights into how microorganisms can influence long-term human health. By understanding the mechanical and chemical strategies this bacterium uses to survive, clinicians can better diagnose, treat, and prevent the severe gastrointestinal diseases it causes. Eradication remains a cornerstone of modern digestive health, transforming a once-permanent infection into a manageable and curable condition.