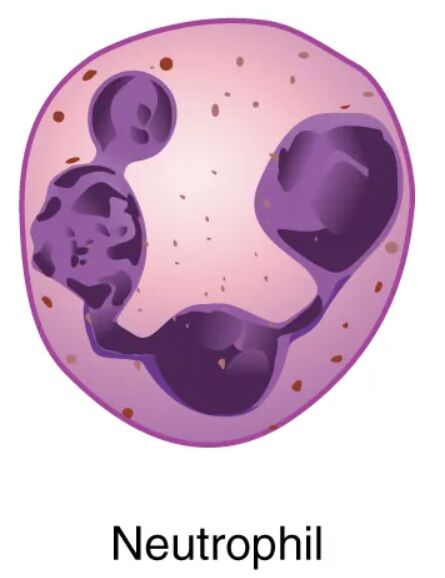

Neutrophils, a key type of granular leukocyte, serve as the body’s first line of defense against bacterial infections, showcasing their critical role in innate immunity. This image provides a detailed microscopic view of a neutrophil, highlighting its distinctive multi-lobed nucleus and light lilac granules, which are essential for its phagocytic function. Delving into this structure offers valuable insights into its rapid response to pathogens and its significance in maintaining health.

Key Components of the Neutrophil

The image focuses on the morphological features that define the neutrophil’s identity and function.

Nucleus:

The nucleus of a neutrophil is multi-lobed, typically featuring two to five segments connected by thin strands, allowing flexibility during migration. This segmented structure aids in the cell’s ability to squeeze through tight spaces as it moves to infection sites.

Granules:

The granules are small, light lilac-staining structures within the cytoplasm, containing enzymes and antimicrobial proteins like myeloperoxidase. These granules are released during phagocytosis to destroy engulfed pathogens, enhancing the neutrophil’s defensive capabilities.

Cytoplasm:

The cytoplasm surrounds the nucleus and granules, appearing pale and supportive, providing the cellular framework for movement and function. It contains the necessary organelles and cytoskeleton to facilitate the neutrophil’s rapid response to inflammation.

The Anatomical and Physiological Role of the Neutrophil

Neutrophils are the most abundant white blood cells, originating in the bone marrow, and their nucleus with multiple lobes enables them to navigate through tissues effectively. The granules, filled with bactericidal substances such as lysozyme and lactoferrin, are released during phagocytosis, a process where neutrophils engulf and digest bacteria, often forming pus as a byproduct. The cytoplasm supports this activity by housing the actin cytoskeleton, which drives the cell’s amoeboid movement toward infection sites guided by chemotactic signals.

Production of neutrophils is regulated by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), released in response to infection, with thyroid hormones like T3 and T4 indirectly influencing metabolic demand that affects hematopoiesis. After a short lifespan of hours to days, neutrophils undergo apoptosis or are removed by macrophages, preventing excessive inflammation. Their rapid mobilization and potent antimicrobial action make them indispensable in acute infections.

- Phagocytosis Process: Engulfs bacteria within minutes; releases reactive oxygen species to kill pathogens.

- Granule Content: Myeloperoxidase generates hypochlorous acid; defensins create pores in bacterial membranes.

- Migration Ability: Lobed nucleus enhances deformability; chemotaxis directs movement via interleukin-8.

Physical Characteristics and Clinical Relevance

The physical appearance of the neutrophil under the microscope reflects its functional design, with the nucleus’s segmentation providing flexibility and the granules’ light staining indicating their enzyme-rich nature. The cytoplasm’s pale hue supports the cell’s mobility, allowing it to traverse endothelial barriers during emigration. These features are critical for identifying neutrophils in blood smears, where their abundance can signal active immune responses.

Clinically, neutrophil counts are a key diagnostic marker. Elevated levels, or neutrophilia, often indicate bacterial infections or inflammation, assessed via complete blood count (CBC) with differential, while low counts, or neutropenia, may suggest bone marrow suppression or chemotherapy effects, increasing infection risk. Treatments include G-CSF to boost production in neutropenia or antibiotics for underlying infections, with microscopic analysis guiding therapeutic decisions.

- Diagnostic Tools: Wright’s stain highlights granule color; flow cytometry quantifies neutrophil subsets.

- Therapeutic Approaches: Broad-spectrum antibiotics target bacterial causes; stem cell transplants address severe neutropenia.

Conclusion

The granular leukocyte neutrophil image provides a close-up view of a cell designed for swift and effective immune defense, with its lobed nucleus and enzyme-packed granules at the forefront. This microscopic perspective underscores the neutrophil’s vital role in combating bacterial threats and maintaining tissue integrity. By understanding its structure and function, one can better appreciate the diagnostic and treatment strategies that leverage neutrophils to support overall health and resilience.