Bacterial vaginosis is a common vaginal dysbiosis characterized by a significant shift in microbial flora, moving away from protective species toward an overgrowth of anaerobic organisms. The identification of Gardnerella vaginalis and its hallmark “clue cells” on a Pap smear or wet mount is a critical diagnostic step in managing this condition and preventing associated reproductive health complications.

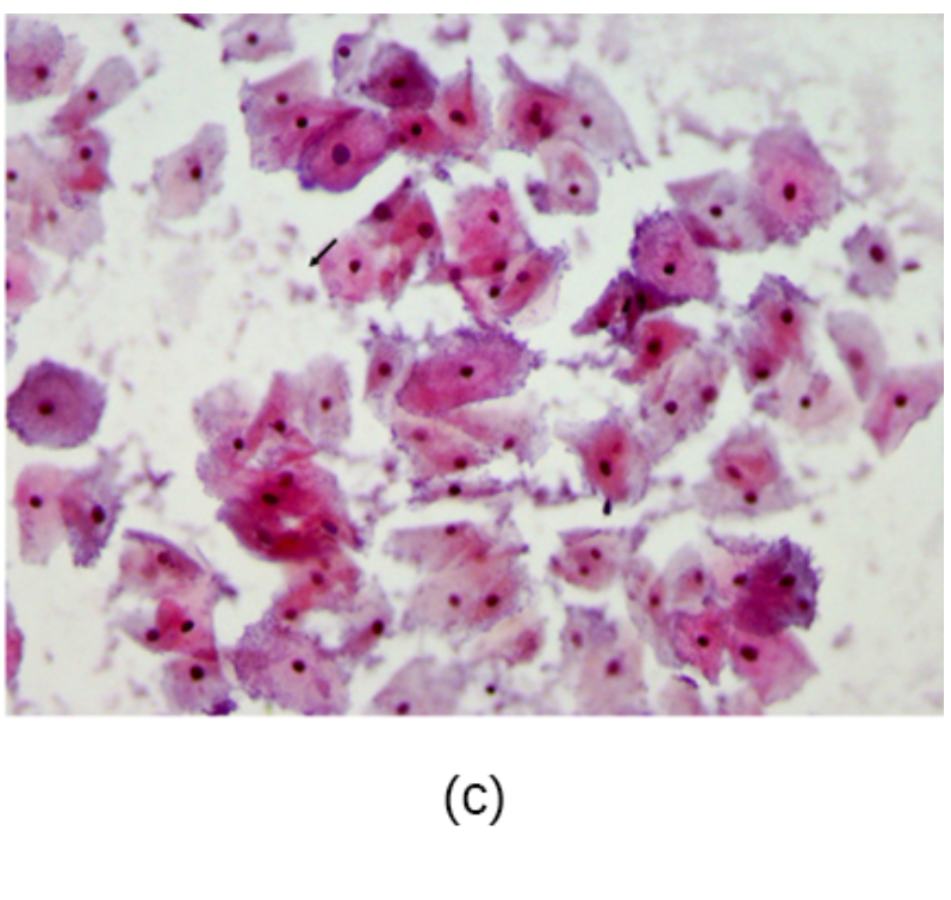

(c): This label denotes the specific micrograph section identifying the presence of the gram-variable organism Gardnerella vaginalis within a clinical sample. This visual evidence provides a clear representation of how these opportunistic bacteria interact with human tissue during a symptomatic episode.

Arrow (pointing to a cell): This arrow highlights a diagnostic “clue cell,” which is a squamous epithelial cell so heavily colonized by bacteria that its edges appear stippled or “fuzzy.” Clinicians look for these specific cells because their presence indicates that the bacterial load has reached a level sufficient to disrupt the normal vaginal environment.

Gardnerella vaginalis is a facultative anaerobic coccobacillus that serves as a primary marker for bacterial vaginosis (BV). While it can be found in small amounts in a healthy vaginal tract, its rapid proliferation often signifies a loss of the normal, acidic environment. This shift is typically marked by a decrease in Lactobacillus species, which normally produce lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide to keep the vaginal pH between 3.8 and 4.5.

The image provided is a Pap smear, a common screening tool that occasionally reveals the presence of BV even when a patient is asymptomatic. In the micrograph, the stained epithelial cells are surrounded by a dense “sand-like” appearance of bacteria. When these bacteria adhere to the surface of the host cells, they create the characteristic clue cell appearance that is central to laboratory confirmation.

Diagnosing this condition often relies on a combination of clinical observations and laboratory findings. The most frequent indicators used by healthcare providers include:

- Presence of thin, homogeneous, white-to-grey vaginal discharge.

- A vaginal pH measured at greater than 4.5.

- A positive “whiff test,” where a fishy odor is released upon the addition of potassium hydroxide (KOH) to the discharge.

- The microscopic observation of clue cells on a saline wet mount, accounting for at least 20% of total epithelial cells.

The Pathogenesis of Bacterial Vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis is not considered a traditional infection caused by a single pathogen but rather a complex ecological imbalance. Gardnerella vaginalis acts as a “scaffold” organism, initiating the formation of a dense biofilm on the vaginal epithelium. This biofilm provides a protected environment where other anaerobic bacteria, such as Atopobium vaginae and Mobiluncus species, can thrive. As these anaerobes multiply, they produce metabolic byproducts called amines, which are responsible for the characteristic malodor associated with the condition.

The physiological impact of this shift is significant. The rise in pH and the presence of bacterial enzymes, such as sialidases and prolidases, break down the protective mucus layer of the vagina. This degradation makes the host more susceptible to other infections, including sexually transmitted infections (STIs) like HIV, gonorrhea, and chlamydia. Furthermore, in pregnant individuals, the inflammatory environment created by BV is linked to an increased risk of preterm labor and low birth weight.

Clinical Management and Diagnostics

In a clinical setting, providers often utilize the Amsel criteria to make a rapid bedside diagnosis. This system requires at least three of the four hallmark signs (discharge, pH, odor, and clue cells) to be present. For more detailed laboratory analysis, the Nugent score may be used, which is a Gram-stain-based scoring system that evaluates the balance between different bacterial morphotypes.

Treatment is generally indicated for symptomatic patients or those undergoing certain gynecological procedures. The gold standard of care involves the use of antibiotics such as metronidazole or clindamycin, which can be administered either orally or intravaginally. These medications specifically target the anaerobic overgrowth while allowing the native flora to eventually recover. It is important to note that while BV is associated with sexual activity, treating the male partner has not been shown to reduce recurrence rates in women, though research into the role of the penile microbiome continues.

Understanding the microscopic presentation of Gardnerella vaginalis is essential for modern women’s healthcare. By recognizing the transition of a clear epithelial cell into a bacteria-laden clue cell, pathologists and clinicians can provide accurate diagnoses that lead to effective treatment. Maintaining the delicate microbial balance of the vaginal tract remains a primary goal in preventing the long-term reproductive complications associated with this prevalent condition.