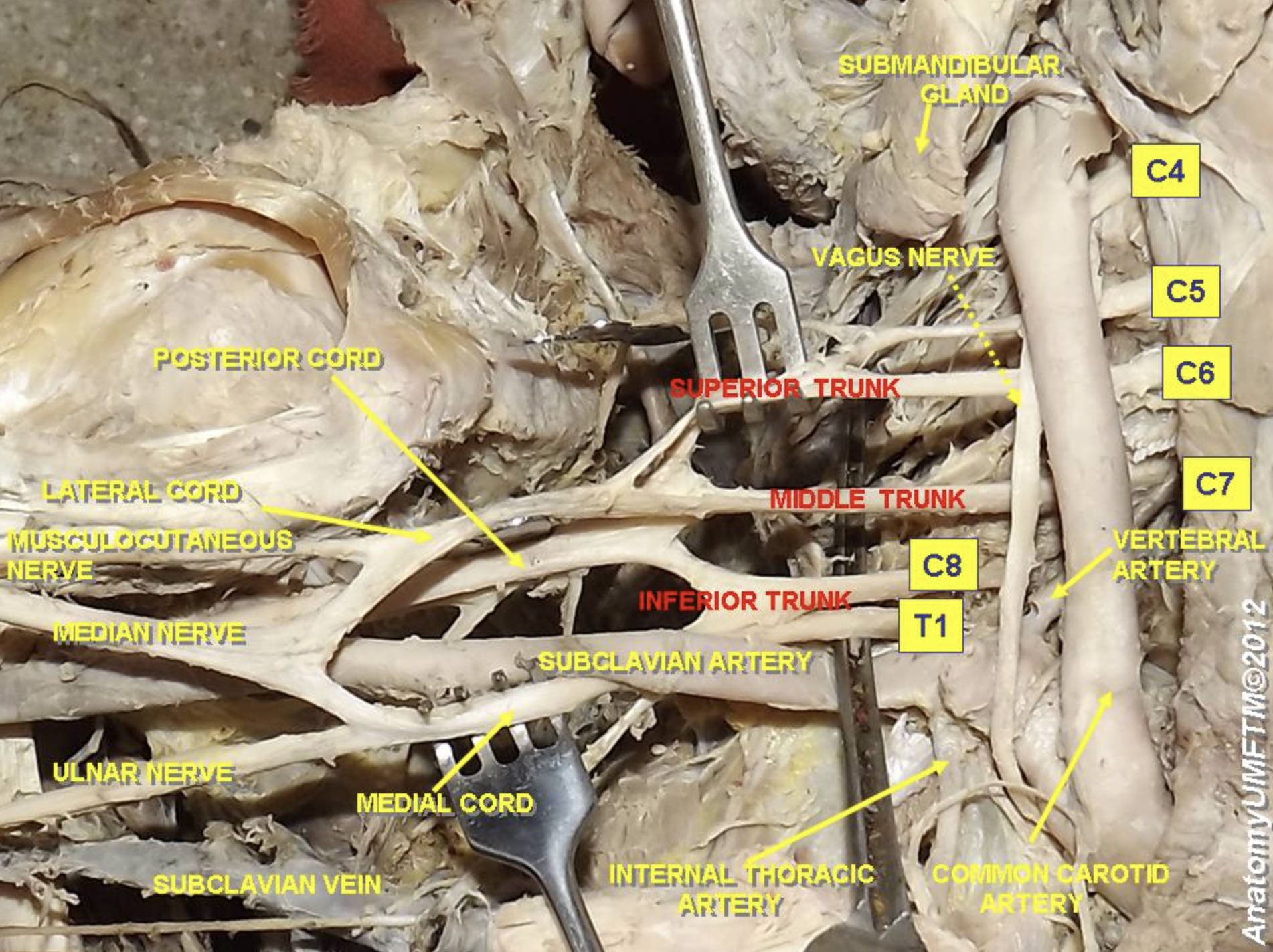

This comprehensive anatomical overview explores the complex interface between the brachial plexus, the common carotid artery, and the major vessels of the thoracic outlet. Using a high-fidelity cadaveric specimen, we detail the roots, trunks, and cords that provide innervation to the upper limb, alongside the arterial pathways critical for systemic circulation and cerebral perfusion.

SUBMANDIBULAR GLAND: This major salivary gland is located in the submandibular triangle and produces the majority of unstimulated saliva. It is a critical structure to identify during neck dissections to avoid damage to the nearby marginal mandibular nerve.

VAGUS NERVE: This tenth cranial nerve provides extensive parasympathetic innervation to the thoracic and abdominal viscera. In the neck, it descends within the carotid sheath between the common carotid artery and the internal jugular vein.

C4: This cervical nerve root primarily contributes to the cervical plexus and the formation of the phrenic nerve. In this dissection, it serves as an anatomical landmark for the superior-most extent of the cervical spinal nerves.

C5: This nerve root is the first primary contributor to the superior trunk of the brachial plexus. It provides essential motor fibers for the deltoid and biceps muscles via the axillary and musculocutaneous nerves.

C6: Along with C5, this nerve root forms the superior trunk of the plexus. It is vital for the sensation of the thumb and index finger and supports movements like wrist extension.

C7: This root continues independently to form the middle trunk of the brachial plexus. It provides the largest contribution to the radial nerve, which controls the extension of the arm and hand.

C8: Arising from below the seventh cervical vertebra, this root joins T1 to form the inferior trunk. It is a key component for the intrinsic muscles of the hand and sensation in the ring and little fingers.

T1: This thoracic nerve root contributes to the inferior trunk and provides autonomic fibers for the eye via the sympathetic chain. Damage to this root can lead to significant hand weakness or clinical signs such as Horner’s syndrome.

VERTEBRAL ARTERY: This vessel arises from the first part of the subclavian artery and ascends through the transverse foramina of the cervical vertebrae. It eventually joins the opposite side to form the basilar artery, supplying oxygenated blood to the posterior brain.

COMMON CAROTID ARTERY: This is the main arterial conduit for blood traveling from the heart toward the head and face. On the left, it arises from the aortic arch, while on the right, it originates from the brachiocephalic trunk.

SUPERIOR TRUNK: Formed by the union of C5 and C6 roots, this trunk is a common site for traction injuries like Erb’s palsy. It carries fibers that eventually split into anterior and posterior divisions for the lateral and posterior cords.

MIDDLE TRUNK: This structure is the direct continuation of the C7 nerve root. It plays a central role in transmitting signals for the radial and median nerves to facilitate complex limb movements.

INFERIOR TRUNK: Resulting from the fusion of C8 and T1 roots, this trunk is positioned just superior to the first rib. Compression in this area is a primary cause of neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome.

POSTERIOR CORD: Formed by the posterior divisions of all three trunks, this cord supplies the extensor muscles of the upper limb. Its terminal branches include the axillary and radial nerves.

LATERAL CORD: This cord is derived from the anterior divisions of the superior and middle trunks. It contributes the lateral root of the median nerve and gives off the musculocutaneous nerve.

MEDIAL CORD: Formed by the anterior division of the inferior trunk, it provides the medial root of the median nerve. It also continues as the ulnar nerve, which is essential for fine motor tasks in the hand.

MUSCULOCUTANEOUS NERVE: This terminal branch of the lateral cord pierces the coracobrachialis muscle to supply the anterior arm. It provides motor control for elbow flexion and sensory input for the lateral forearm.

MEDIAN NERVE: Arising from both the lateral and medial cords, this nerve travels through the carpal tunnel at the wrist. It is responsible for most of the forearm flexors and the precision movements of the thumb.

ULNAR NERVE: Often called the “funny bone” nerve, this terminal branch of the medial cord passes behind the medial epicondyle. It innervates the majority of the small muscles in the hand that perform delicate tasks.

SUBCLAVIAN ARTERY: This high-pressure vessel supplies blood to the arm and neck. It is divided into three parts by the anterior scalene muscle and is a frequent site for surgical bypass procedures.

SUBCLAVIAN VEIN: This large vessel serves as the primary drainage route for the upper limb. It joins the internal jugular vein to form the brachiocephalic vein, returning blood to the heart.

INTERNAL THORACIC ARTERY: Also known as the internal mammary artery, it arises from the subclavian artery and descends inside the chest wall. It is frequently harvested by surgeons for use in coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

Functional Organization of the Brachial Plexus

The brachial plexus is an intricate biological circuit board that originates from the spinal cord and orchestrates the movements and sensations of the arm. It is organized into a hierarchy of roots, trunks, divisions, cords, and terminal branches. This tiered structure allows for a redundant supply of nerves to individual muscles, ensuring that a single root injury does not necessarily lead to total paralysis of a specific muscle group.

In the cervical region, the plexus lies deep within the posterior triangle of the neck, emerging between the anterior and middle scalene muscles. This narrow passage is a critical area for clinical assessment, as both nerves and blood vessels must navigate this tight space to reach the arm. Understanding the physical layout of these structures is the cornerstone of regional anesthesia, particularly for administering interscalene nerve blocks.

Major components of this network include:

- Five Roots (C5-T1) emerging from the intervertebral foramina.

- Three Trunks (Superior, Middle, and Inferior) formed in the neck.

- Six Divisions (Anterior and Posterior) located behind the clavicle.

- Three Cords (Lateral, Posterior, and Medial) named for their relationship to the axillary artery.

- Five Terminal Branches providing motor and sensory function to the limb.

The Interplay Between Vascular and Neural Pathways

The proximity of the brachial plexus to the subclavian artery and common carotid artery highlights the integrated nature of the body’s life-support systems. While the nerves transmit the electrical impulses necessary for motion, the arteries provide the oxygen and nutrients required for cellular metabolic activity. The thoracic outlet represents the bottleneck where these two systems converge, and any structural abnormality in this region, such as a cervical rib, can lead to chronic compression symptoms.

Physiologically, the common carotid artery is essential for cerebral autoregulation. It houses the carotid sinus, a baroreceptor that monitors blood pressure and sends signals to the brain to maintain cardiovascular stability. Similarly, the vertebral artery provides the blood supply for the posterior circulation of the brain, including the brainstem and cerebellum. Damage or plaque buildup in these vessels can lead to transient ischemic attacks or major strokes, emphasizing the importance of vascular health in overall neurological function.

The terminal branches like the median and ulnar nerves allow for the incredible dexterity of the human hand. These nerves must travel long distances from the neck to the fingertips, passing through various potential entrapment points like the elbow or wrist. For instance, the upper extremity depends on the median nerve for the power and precision of the “pincer grasp,” a movement that is uniquely developed in humans for tool use and fine motor tasks.

In summary, the anatomy shown in this cadaveric dissection is a map of human capability and vulnerability. From the autonomic functions of the vagus nerve to the complex motor patterns of the brachial plexus, every structure is part of a finely tuned system. A thorough grasp of these relationships allows healthcare providers to navigate the neurovascular bundle with precision, whether they are performing a physical exam, interpreting imaging, or undertaking complex surgery.