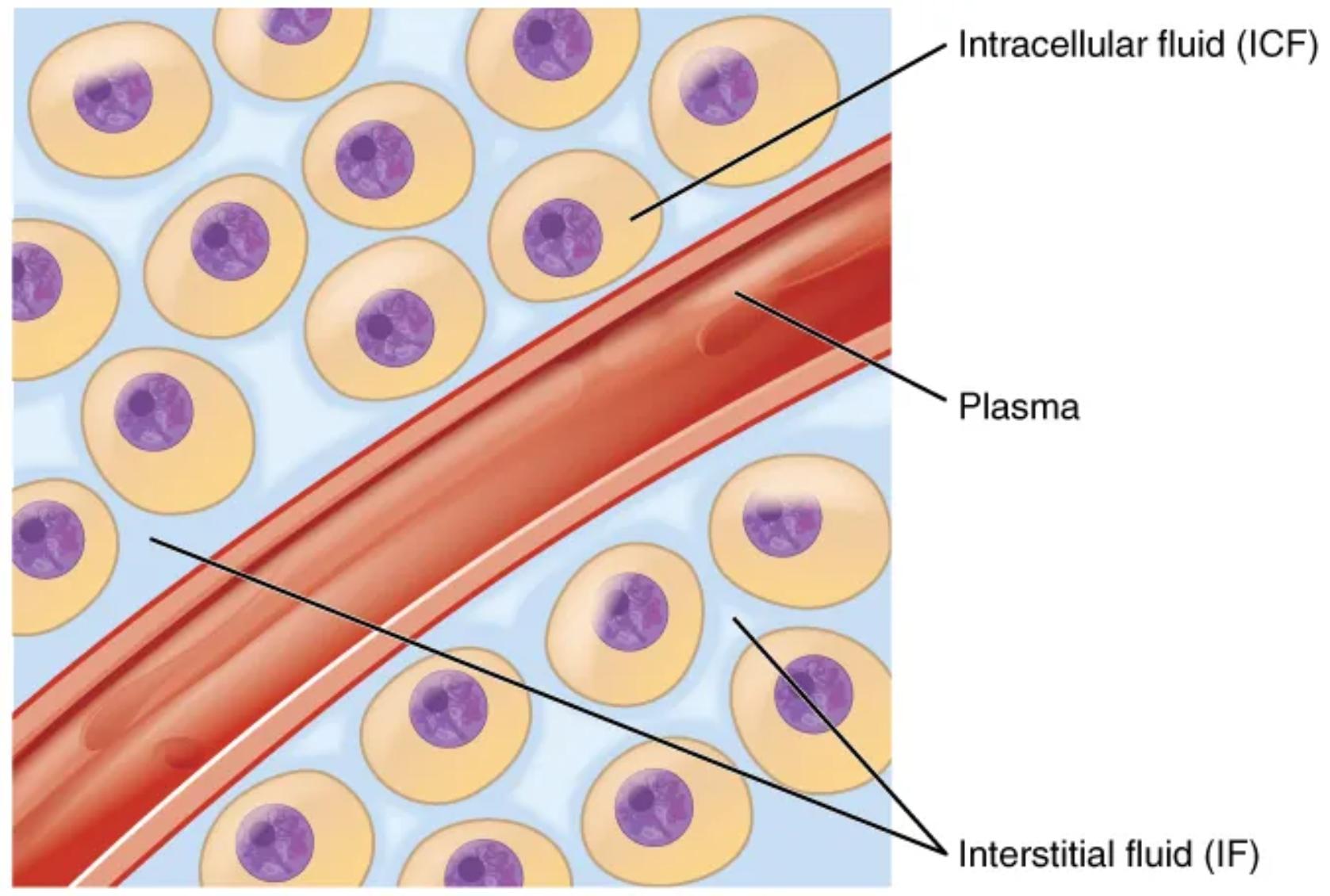

The human body is an intricate network where fluids constantly move and interact, maintaining life-sustaining processes. This diagram offers a clear visualization of the major fluid compartments: intracellular fluid (ICF), interstitial fluid (IF), and plasma. These compartments, though distinct, are in dynamic equilibrium, facilitating the exchange of nutrients, gases, and waste products vital for cellular function and overall physiological stability. Understanding these fluid divisions is fundamental to comprehending fluid balance, electrolyte regulation, and the pathophysiology of numerous conditions.

Intracellular fluid (ICF): The intracellular fluid (ICF) is the fluid found within the cells.

The intracellular fluid (ICF) represents the largest fluid compartment in the body, accounting for approximately two-thirds of the total body water. This fluid is critical for maintaining cell shape, supporting metabolic reactions, and facilitating the numerous biochemical processes essential for cell survival and function. The unique composition of the ICF, distinct from the extracellular environment, is actively maintained by cellular mechanisms, including ion pumps.

Plasma: Plasma is the liquid component of blood, making up the intravascular fluid.

Plasma is the fluid component of blood, and it constitutes approximately 20% of the extracellular fluid (ECF). This compartment plays a crucial role in transporting blood cells, nutrients, hormones, antibodies, and waste products throughout the body. It also contributes significantly to maintaining blood pressure and body temperature.

Interstitial fluid (IF): The interstitial fluid (IF) is part of the extracellular fluid (ECF) found between the cells.

Interstitial fluid (IF) surrounds the body’s cells, acting as a direct medium for the exchange of substances between the blood and cells. It makes up about 80% of the extracellular fluid and is crucial for delivering oxygen and nutrients to tissues while simultaneously removing metabolic waste products. The composition of the IF is carefully regulated to ensure optimal cellular environments.

The precise distribution and movement of fluids among these compartments are vital for maintaining homeostasis, the body’s stable internal environment. The constant exchange between plasma, interstitial fluid, and intracellular fluid ensures that cells receive the necessary resources and that metabolic byproducts are efficiently removed. This dynamic process is largely governed by hydrostatic and osmotic pressures, which regulate the flow of water and solutes across cell membranes and capillary walls.

For instance, nutrients like glucose and oxygen, transported in the plasma, must first move into the interstitial fluid before they can enter the cells (ICF). Similarly, waste products from cellular metabolism travel from the ICF to the IF and then into the plasma for excretion. This continuous circulation is essential for:

- Delivering oxygen and nutrients to tissues.

- Removing carbon dioxide and metabolic waste.

- Maintaining stable body temperature.

- Facilitating immune responses and hormone distribution.

Disruptions in the balance of these fluid compartments, such as dehydration, edema, or electrolyte imbalances, can have profound physiological consequences. For example, excessive fluid loss from the extracellular compartment (plasma and IF) can lead to reduced blood volume, affecting blood pressure and organ perfusion. Conversely, an accumulation of fluid in the interstitial space results in edema, which can impair tissue function.

Understanding the fluid compartments is a cornerstone in clinical medicine, guiding therapeutic interventions for conditions ranging from kidney disease and heart failure to severe burns and shock. By monitoring fluid intake, output, and electrolyte levels, healthcare professionals can effectively manage patient care and restore fluid balance. The body’s ability to regulate these compartments is a testament to its remarkable adaptive capabilities.

In conclusion, the fluid compartments of the human body are not merely passive reservoirs but active participants in the maintenance of life. The diagram vividly illustrates this intricate system, emphasizing the interconnectedness of intracellular fluid, plasma, and interstitial fluid. A thorough understanding of these fluid dynamics is indispensable for comprehending normal physiological function and for recognizing the underlying mechanisms of many pathological states, offering a foundation for effective medical practice.