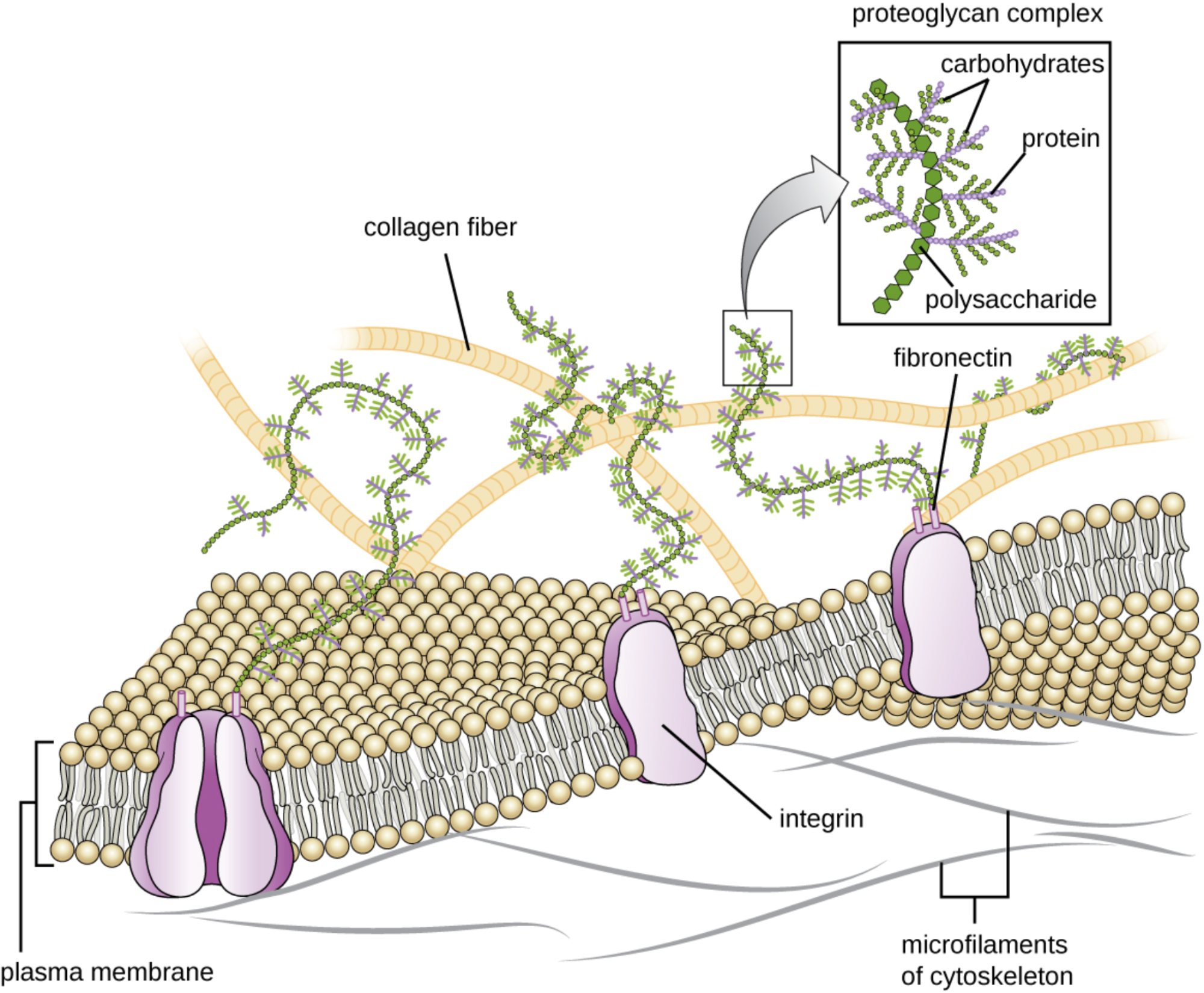

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is a complex network of proteins and carbohydrates that provides structural and biochemical support to surrounding cells. This intricate scaffold not only maintains tissue integrity but also facilitates essential cellular communication and protects tissues from mechanical stress. By serving as a dynamic environment for growth and signaling, the ECM is fundamental to the physiological health and functional coordination of every organ system in the human body.

plasma membrane: This is the selective lipid bilayer that encloses the cytoplasm, acting as the primary barrier between the intracellular and extracellular environments. It provides the docking sites for proteins like integrins, which anchor the cell to the surrounding matrix.

collagen fiber: Representing the most abundant protein in the human body, these thick fibers provide exceptional tensile strength and structural support to various tissues. They form a resilient network that helps the extracellular matrix resist pulling forces and maintain its shape.

proteoglycan complex: These are specialized molecules consisting of a central protein core with numerous carbohydrate chains attached, often appearing like a bottle brush. They are highly effective at trapping water, which creates a hydrated gel that resists compression and cushions the cells.

carbohydrates: These are the glycan chains that extend from the protein core in a proteoglycan complex, contributing to the overall volume and hydration of the matrix. They play a vital role in cell-to-cell recognition and the sequestration of growth factors within the tissue.

protein: Within the proteoglycan complex, the protein serves as the central axis to which carbohydrate chains are covalently bonded. This structural arrangement is essential for the stabilization of the matrix and the proper orientation of its components.

polysaccharide: Often referring to long chains like hyaluronic acid, these molecules act as the backbone for the large proteoglycan aggregates found in the matrix. They help regulate tissue permeability and facilitate the movement of cells through the extracellular space.

fibronectin: This is an adhesive glycoprotein that bridges the gap between the extracellular matrix and the cell surface. By binding both to collagen fibers and integrin proteins, it ensures that the cell remains firmly attached to its structural environment.

integrin: These transmembrane proteins span the plasma membrane to connect the extracellular components with the internal cytoskeleton. They are crucial for transmitting mechanical signals from the outside world into the cell, triggering specific physiological responses.

microfilaments of cytoskeleton: Primarily composed of actin, these internal fibers provide the mechanical framework necessary for cell shape and motility. They are linked to the extracellular matrix through integrins, allowing for a coordinated structural unit between the cell and its environment.

The Functional Significance of the Extracellular Scaffold

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is much more than a simple biological glue; it is a dynamic and essential component of all multicellular organisms. This complex scaffold consists of a diverse array of macromolecules secreted by local cells, such as fibroblasts, to create a microenvironment tailored to the specific needs of the tissue. Whether it is the hard mineralized matrix of bone or the transparent, flexible matrix of the cornea, the ECM provides the physical cues necessary for cell survival and differentiation.

One of the most remarkable features of the ECM is its ability to act as a signaling hub. Through a process called mechanotransduction, physical forces acting on the outside of the tissue are converted into biochemical signals inside the cell. This allows tissues to adapt to changes in mechanical load, such as the strengthening of tendons in response to exercise or the remodeling of blood vessels in response to blood pressure changes.

Essential functions of the extracellular matrix include:

- Providing mechanical support and structural integrity to tissues and organs.

- Regulating cellular behaviors such as proliferation, migration, and apoptosis.

- Storing and sequestering growth factors for localized release during wound healing.

- Serving as a physical filter for the diffusion of nutrients and metabolic wastes.

Physiological Coordination and Tissue Health

The interaction between the ECM and the cell is a two-way street. Cells constantly modify their surroundings by secreting enzymes known as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which break down old components to allow for tissue remodeling. This process is vital during embryonic development and tissue repair. The integration of the matrix with the internal cytoskeleton via integrin proteins ensures that the entire tissue functions as a unified mechanical entity, which is paramount for organs like the heart that experience constant rhythmic stress.

The hydration levels of the matrix, primarily managed by proteoglycans, are crucial for the health of cartilage and joints. Because these molecules are negatively charged, they attract water, creating a turgid environment that can absorb shock. If the balance of these components is disrupted, as seen in various degenerative conditions, the tissue loses its ability to handle physical stress, leading to a decline in organ function. Researchers in the field of tissue engineering are currently studying these components to create synthetic scaffolds that can help regrow damaged organs.

In summary, the extracellular matrix is an indispensable architect of human physiology. It provides the necessary strength, flexibility, and communication pathways required for complex biological life. By balancing the rigid support of collagen with the hydrated cushioning of proteoglycans, the ECM maintains the structural homeostasis of the body. Understanding this microscopic landscape is essential for advancing our knowledge of histology, wound healing, and the development of regenerative medical therapies.