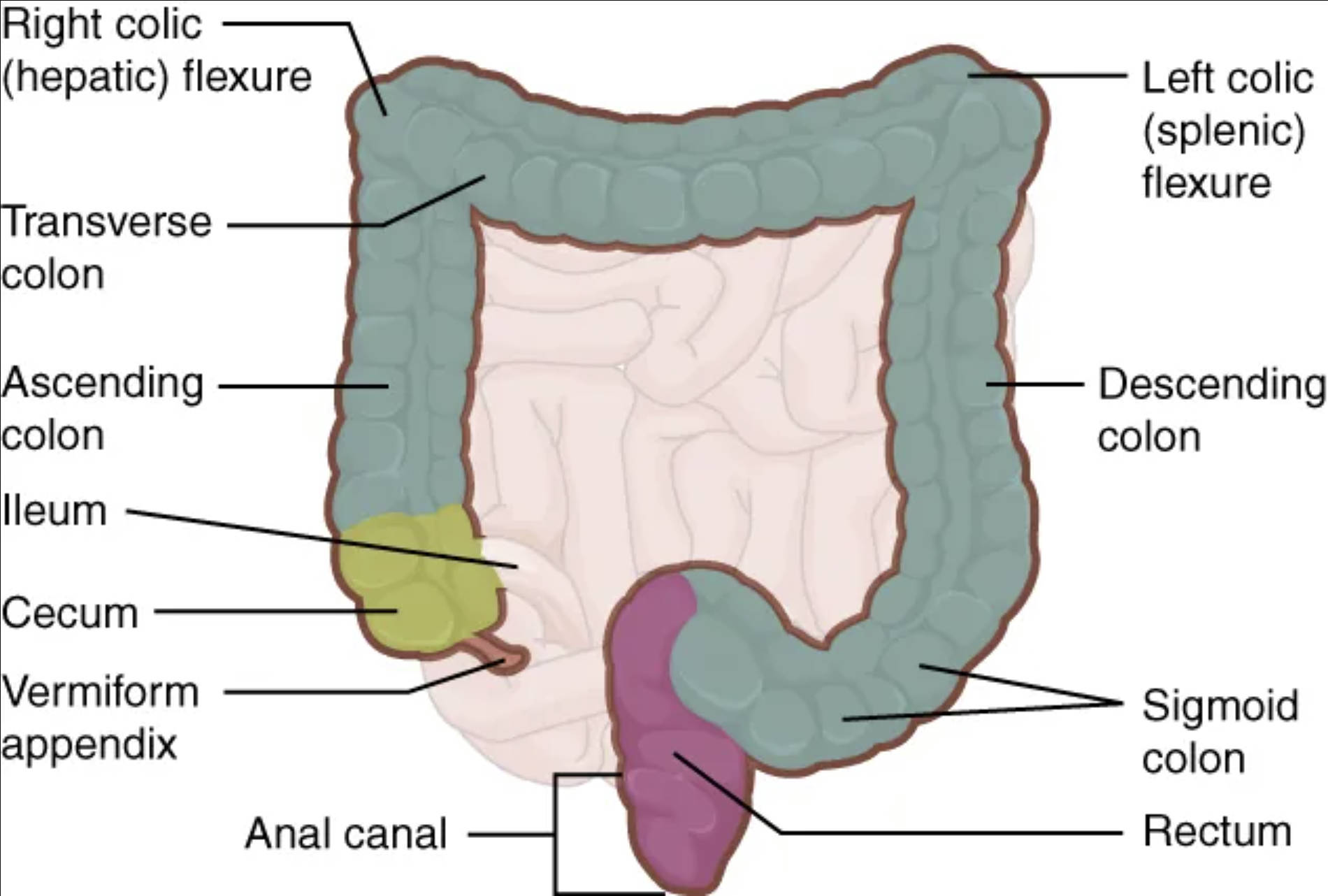

Discover the intricate anatomy of the large intestine, a crucial component of the digestive system responsible for water absorption, electrolyte balance, and waste elimination. This detailed guide explores its key segments—the cecum, colon (ascending, transverse, descending, sigmoid), and rectum—providing a comprehensive understanding of how these structures work together to form and excrete feces, maintaining overall digestive health.

Right colic (hepatic) flexure: This is the bend in the colon located beneath the liver, where the ascending colon transitions into the transverse colon. It is named “hepatic” due to its close proximity to the liver.

Transverse colon: This segment of the colon extends horizontally across the upper abdomen, from the right colic flexure to the left colic flexure. It lies anterior to the small intestine and plays a significant role in water absorption and fecal formation.

Ascending colon: This section of the large intestine travels upwards on the right side of the abdominal cavity, from the cecum to the right colic flexure. Its primary function is to absorb residual water and electrolytes from the chyme.

Ileum: While primarily part of the small intestine, the ileum is depicted here connecting to the cecum via the ileocecal valve. It is the final segment of the small intestine, responsible for absorbing vitamin B12 and bile salts before passing undigested material to the large intestine.

Cecum: This is a blind-ended pouch located at the beginning of the large intestine, receiving chyme from the ileum. It is considered the first part of the large intestine and is where the vermiform appendix is typically attached.

Vermiform appendix: A small, finger-like projection extending from the cecum, often considered a vestigial organ, though it may play a role in immune function. Its inflammation leads to the medical condition known as appendicitis.

Anal canal: This is the final 3-4 cm segment of the large intestine, extending from the rectum to the anus. It contains internal and external sphincters that control the expulsion of feces during defecation.

Left colic (splenic) flexure: This is the bend in the colon located beneath the spleen, marking the transition from the transverse colon to the descending colon. It is named “splenic” due to its proximity to the spleen.

Descending colon: This section of the large intestine travels downwards on the left side of the abdominal cavity, from the left colic flexure to the sigmoid colon. Its main role is to store feces before their elimination.

Sigmoid colon: This S-shaped segment of the colon connects the descending colon to the rectum. Its strong muscular walls propel feces towards the rectum, and it is a common site for diverticular disease.

Rectum: This is the final straight portion of the large intestine, approximately 15 cm long, extending from the sigmoid colon to the anal canal. It serves as a temporary storage area for feces, accumulating them before defecation.

The large intestine, also known as the colon, represents the final major segment of the digestive tract, playing a crucial role in waste management and maintaining fluid balance within the body. While the small intestine is the primary site for nutrient absorption, the large intestine is predominantly involved in absorbing residual water and electrolytes from indigestible food matter, forming and storing feces, and hosting a vast community of beneficial gut bacteria. Its distinct anatomical structure, characterized by a wider diameter and sacculations called haustra, is perfectly adapted for these functions.

This critical organ typically measures about 1.5 meters (5 feet) in length in adults and is strategically positioned to process the material that remains after most nutrients have been extracted. Its journey begins in the lower right quadrant of the abdomen, ascending upwards, traversing horizontally, and then descending, culminating in the expulsion of waste. A comprehensive understanding of its various segments—the cecum, colon, and rectum—is essential for appreciating the intricate processes that contribute to overall digestive health.

The functions of the large intestine extend beyond simple waste elimination. It plays a vital role in synthesizing certain vitamins, particularly vitamin K and some B vitamins, through the action of its resident microbial flora. Moreover, it is crucial for maintaining the body’s hydration and electrolyte balance, as significant amounts of water and salts are reabsorbed here. Any disruption to the normal functioning of the large intestine can lead to common digestive issues such as constipation, diarrhea, and more severe conditions like inflammatory bowel disease.

The large intestine is broadly divided into three main regions: the cecum, the colon, and the rectum. Each region has specific anatomical features and functional contributions to the overall process of waste elimination.

The Cecum and Vermiform Appendix

The cecum is the first part of the large intestine, a small, blind-ended pouch located in the lower right abdomen. It receives undigested chyme from the ileum of the small intestine via the ileocecal valve, which prevents reflux. Attached to the inferior aspect of the cecum is the vermiform appendix, a slender, finger-like projection. Though historically considered vestigial, the appendix is now believed to play a role in immune function, potentially serving as a safe house for beneficial gut bacteria. Inflammation of the appendix, known as appendicitis, is a common surgical emergency.

The Colon: Ascending, Transverse, Descending, and Sigmoid

The colon is the longest and most extensive part of the large intestine, further subdivided into four segments:

- Ascending Colon: This segment extends upwards from the cecum on the right side of the abdominal cavity. Its primary role is to continue the absorption of water and electrolytes, solidifying the fecal matter.

- Right Colic (Hepatic) Flexure: This sharp bend marks the transition from the ascending colon to the transverse colon, located near the liver.

- Transverse Colon: Stretching across the upper abdomen, this segment is the most mobile part of the colon. It continues water and electrolyte absorption and connects the right and left colic flexures.

- Left Colic (Splenic) Flexure: This sharp bend occurs near the spleen, marking the transition from the transverse colon to the descending colon.

- Descending Colon: Running downwards on the left side of the abdominal cavity, this segment primarily serves as a storage site for feces.

- Sigmoid Colon: An S-shaped segment that connects the descending colon to the rectum. Its strong muscular contractions help propel feces towards the rectum, and it is a common site for diverticulosis and diverticulitis.

The Rectum and Anal Canal: Storage and Elimination

The rectum is the final straight segment of the large intestine, approximately 15 cm long. Its primary function is to store feces temporarily before defecation. The rectum’s walls contain stretch receptors that signal the urge to defecate when filled. The anal canal is the terminal 3-4 cm of the large intestine, opening to the exterior at the anus. It is surrounded by internal (involuntary) and external (voluntary) anal sphincters, which control the passage of feces.

In conclusion, the large intestine is an indispensable part of the digestive system, meticulously designed for its roles in fluid balance, waste processing, and elimination. From the initial reception of chyme in the cecum to the final expulsion of feces through the anal canal, its various segments—the ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid colon, along with the rectum—each contribute to a coordinated process. Understanding the intricate anatomy and functions of the large intestine is paramount for appreciating its contribution to overall physiological well-being and managing common gastrointestinal conditions.