The eukaryotic cell is a marvel of biological engineering, characterized by its complex internal compartmentalization and specialized membrane-bound organelles. Unlike simpler prokaryotic organisms, eukaryotes isolate their biochemical reactions within dedicated structures, allowing for higher metabolic efficiency and the development of multicellular life. This anatomical organization ensures that processes such as energy production, genetic replication, and protein folding can occur simultaneously without interference, maintaining the delicate balance required for human health.

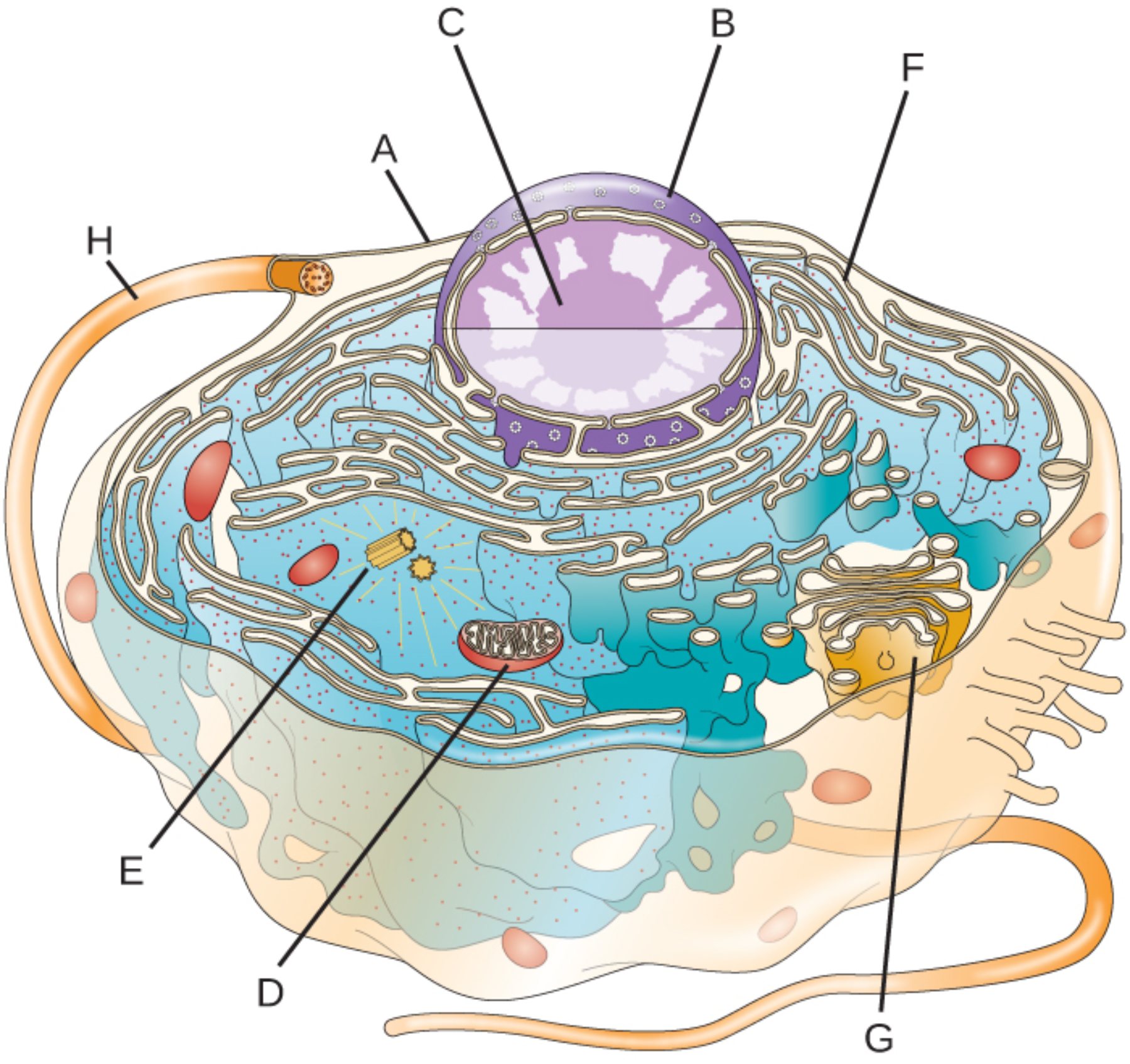

A – Plasma Membrane: This phospholipid bilayer serves as the cell’s outer boundary, maintaining a distinct internal environment from the extracellular fluid. It exhibits selective permeability, allowing only specific ions and molecules to pass through while providing essential structural support and docking sites for signaling proteins.

B – Nuclear Envelope: This double-membrane structure encloses the genetic material and separates the nucleus from the surrounding cytoplasm. It is perforated with specialized nuclear pores that tightly regulate the traffic of proteins, RNA, and other macromolecules between the nucleus and the rest of the cell.

C – Nucleolus: Situated within the heart of the nucleus, this dense, non-membrane-bound region is the primary site of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) synthesis. It acts as the assembly line for the subunits of ribosomes, which are the fundamental machines required for global protein synthesis throughout the cell.

D – Mitochondrion: Often described as the powerhouse of the cell, this organelle is responsible for generating chemical energy through the process of oxidative phosphorylation. It transforms nutrients into adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the universal energy currency that fuels nearly all cellular biochemical reactions and physiological functions.

E – Centrioles: These cylindrical structures are composed of specialized microtubule triplets and are typically found in pairs within the centrosome. They play a pivotal role during cell division by organizing the mitotic spindle, which ensures that chromosomes are accurately distributed to each daughter cell.

F – Rough Endoplasmic Reticulum: This extensive network of folded membranes is studded with ribosomes on its outer surface, giving it a characteristic “rough” appearance. It serves as a major manufacturing hub for proteins that are destined for secretion, incorporation into the plasma membrane, or delivery to other organelles.

G – Golgi Apparatus: Functioning as the cell’s processing and shipping center, this stack of flattened cisternae modifies, sorts, and packages macromolecules. It attaches chemical markers to proteins and lipids, directing them to their final cellular or extracellular destinations via transport vesicles.

H – Flagellum/Cytoskeleton: This long, whip-like projection is an extension of the internal microtubule network that facilitates cellular locomotion. In the human body, such structures are essential for the motility of sperm cells and the movement of fluids across epithelial surfaces in the respiratory and reproductive tracts.

The Foundation of Cellular Complexity

The survival of a multicellular organism depends on the harmonious interaction of trillions of eukaryotic cells. Each cell operates like a microscopic city, with a centralized government in the nucleus and power plants in the mitochondria. This high level of organization allows cells to differentiate into specialized types, such as neurons that transmit electrical signals or myocytes that facilitate muscle contraction. The fluid cytoplasm acts as the medium for this activity, housing the cytoskeleton that provides both shape and a highway system for intracellular transport.

Physiological health begins at the cellular level. When the internal machinery of a cell malfunctions—such as a failure in protein folding within the endoplasmic reticulum or a breakdown in mitochondrial energy production—it can lead to systemic diseases. For example, mitochondrial dysfunction is often linked to metabolic disorders and neurodegenerative conditions, while errors in the Golgi apparatus can disrupt the essential secretion of hormones like insulin or thyroxine.

The primary functions of eukaryotic cells include:

- Maintaining genetic integrity through the protection of DNA within the nucleus.

- Generating high yields of ATP via aerobic respiration to meet high energy demands.

- Synthesizing and secretively transporting complex proteins and lipids.

- Facilitating cellular communication through receptor-ligand interactions on the membrane.

Physiological Integration and Energy Production

One of the most critical aspects of eukaryotic physiology is the relationship between the nucleus and the mitochondria. While the nucleus holds the vast majority of an organism’s genetic code, mitochondria possess their own unique DNA. This dual-genome system requires precise coordination to ensure that the cell has enough energy to replicate its DNA and perform its specialized tasks. The inner membrane of the mitochondrion is folded into cristae to maximize the surface area available for the chemical reactions that produce energy.

Furthermore, the endomembrane system—comprising the nuclear envelope, endoplasmic reticulum, and Golgi apparatus—works as a seamless pipeline. A protein synthesized on the rough ER is immediately shuttled into the Golgi for refinement, such as glycosylation, before being dispatched to where it is needed most. This synchronized flow of biological material is essential for maintaining the structural integrity of the cell and for the systemic release of enzymes and signaling molecules that regulate everything from digestion to the immune response.

In conclusion, the eukaryotic cell is not merely a container for life but a sophisticated ecosystem of specialized parts working in unison. From the protective barrier of the plasma membrane to the energy-harvesting capabilities of the mitochondria, every organelle plays a vital role in sustaining the organism. By understanding the intricate anatomy and physiology of these microscopic units, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complex biological processes that define human life and the medical foundations of health and disease.