The development of the human parietal venous system is a sophisticated biological process that involves the transformation of symmetrical embryonic vessels into a functional, asymmetrical adult network. During early gestation, the venous system is characterized by the cardinal veins, which provide the primary drainage for the embryo’s trunk. As development progresses, selective regression and fusion of these channels occur, ultimately shifting the majority of blood flow to the right side of the body to form the Venae Cavae.

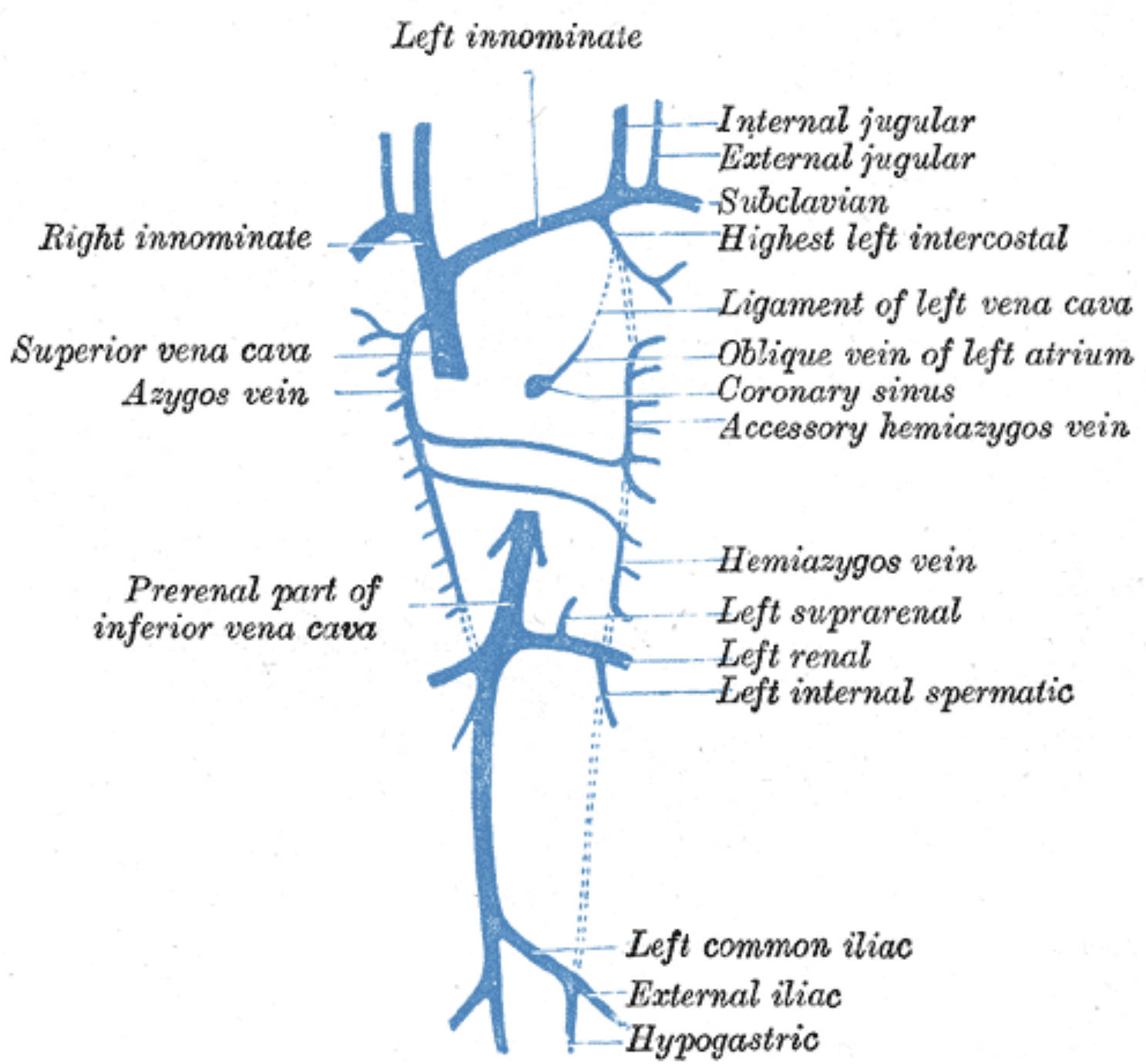

This diagram illustrates the completion of development, highlighting how various remnants and active vessels organize into the definitive anatomy seen in adults. Understanding this transition is essential for medical professionals, particularly in fields such as vascular surgery, radiology, and embryology. The complex arrangement of the azygos and hemiazygos systems serves as a testament to the evolutionary efficiency of human vascular design.

Key components of this developmental timeline include:

- The formation of the brachiocephalic (innominate) veins from the anterior cardinal veins.

- The regression of the left superior vena cava, leaving behind the ligament of the left vena cava and the oblique vein of the left atrium.

- The integration of subcardinal and supracardinal veins to form the inferior vena cava.

- The establishment of the azygos system as a vital drainage route for the thoracic wall.

Left innominate: The left innominate vein, also known as the left brachiocephalic vein, is formed by the union of the internal jugular and subclavian veins. It travels across the upper mediastinum to join its right-sided counterpart, eventually forming the superior vena cava.

Right innominate: The right innominate vein is shorter and more vertical than the left one. It receives blood from the right side of the head, neck, and upper limb before merging into the superior vena cava.

Superior vena cava: This large vessel is responsible for transporting all venous blood from the head, neck, upper limbs, and thorax to the right atrium. It represents the final common pathway for the upper half of the systemic venous system.

Azygos vein: The azygos vein runs along the right side of the thoracic vertebral column and serves as a vital bridge between the superior and inferior venae cavae. It primarily collects blood from the intercostal veins and the posterior thoracic wall.

Prerenal part of inferior vena cava: This segment of the inferior vena cava is located superior to the entry point of the renal veins. It is formed during embryological development from a complex fusion of several embryonic venous channels.

Internal jugular: This major vein collects blood from the brain and the superficial parts of the face and neck. It descends within the carotid sheath alongside the common carotid artery.

External jugular: Unlike the internal jugular, this vein is more superficial and drains blood from the scalp and deep parts of the face. It typically empties into the subclavian vein.

Subclavian: The subclavian vein is the continuation of the axillary vein and drains the entire upper extremity. It passes anterior to the anterior scalene muscle before joining the internal jugular.

Highest left intercostal: This vein, also called the left superior intercostal vein, drains the upper 2-3 intercostal spaces on the left side. It usually empties into the left brachiocephalic vein.

Ligament of left vena cava: This is a fibrous remnant of the left common cardinal vein and the proximal part of the left superior vena cava. It is a classic example of an anatomical structure that loses its lumen during fetal maturation.

Oblique vein of left atrium: Also known as the vein of Marshall, this small vessel is located on the posterior surface of the left atrium. It is another remnant of the left superior vena cava from the embryonic stage.

Coronary sinus: This wide venous channel receives most of the venous drainage from the myocardium. It empties directly into the right atrium, located between the inferior vena cava and the tricuspid valve.

Accessory hemiazygos vein: This vessel drains the middle portion of the left thoracic wall. It typically crosses the vertebral column to join the azygos vein on the right side.

Hemiazygos vein: Running along the lower left side of the spine, this vein drains the lower posterior intercostal spaces. It acts as the left-sided equivalent to the lower portion of the azygos vein.

Left suprarenal: This vein drains the left adrenal gland and typically empties into the left renal vein rather than directly into the IVC. This asymmetrical drainage pattern is an important anatomical detail in surgery.

Left renal: This large vein carries filtered blood from the left kidney to the inferior vena cava. Because it must cross the aorta, it is significantly longer than the right renal vein.

Left internal spermatic: Also known as the left gonadal vein, it drains the left testis or ovary. Unlike the right gonadal vein, it usually joins the left renal vein at a right angle.

Left common iliac: This vein is formed by the union of the external and internal iliac veins near the sacroiliac joint. It merges with the right common iliac vein to form the start of the inferior vena cava.

External iliac: This vessel is the upward continuation of the femoral vein from the lower limb. It carries blood from the leg and enters the pelvis behind the inguinal ligament.

Hypogastric: Also called the internal iliac vein, it drains blood from the pelvic organs and the gluteal region. It joins the external iliac to form the common iliac vein.

Clinical Relevance of the Azygos System

The azygos system serves as a critical collateral circulation pathway within the body. In cases where the inferior vena cava (IVC) or superior vena cava (SVC) becomes obstructed—due to a tumor, thrombosis, or external compression—the azygos and hemiazygos veins can enlarge significantly. This allows blood from the lower body to bypass the obstruction and reach the heart via the SVC, or vice versa, maintaining systemic stability despite major vascular compromise.

Anatomical Variations and Development

The final arrangement of these veins is subject to numerous anatomical variations depending on how the embryonic cardinal veins regress. For example, some individuals may retain a persistent left superior vena cava, which can complicate the placement of central venous catheters or pacemaker leads. Similarly, the way the left renal vein crosses the abdominal aorta makes it susceptible to compression, a condition known as Nutcracker syndrome, which can lead to hematuria and pelvic pain.

A deep understanding of the parietal venous system is fundamental for interpreting diagnostic imaging and performing safe surgical interventions. By recognizing the embryonic origins of these vessels, clinicians can better predict variations and manage vascular pathologies with precision. The transition from a symmetrical fetal state to the complex, integrated adult system highlights the remarkable adaptability of human anatomy.