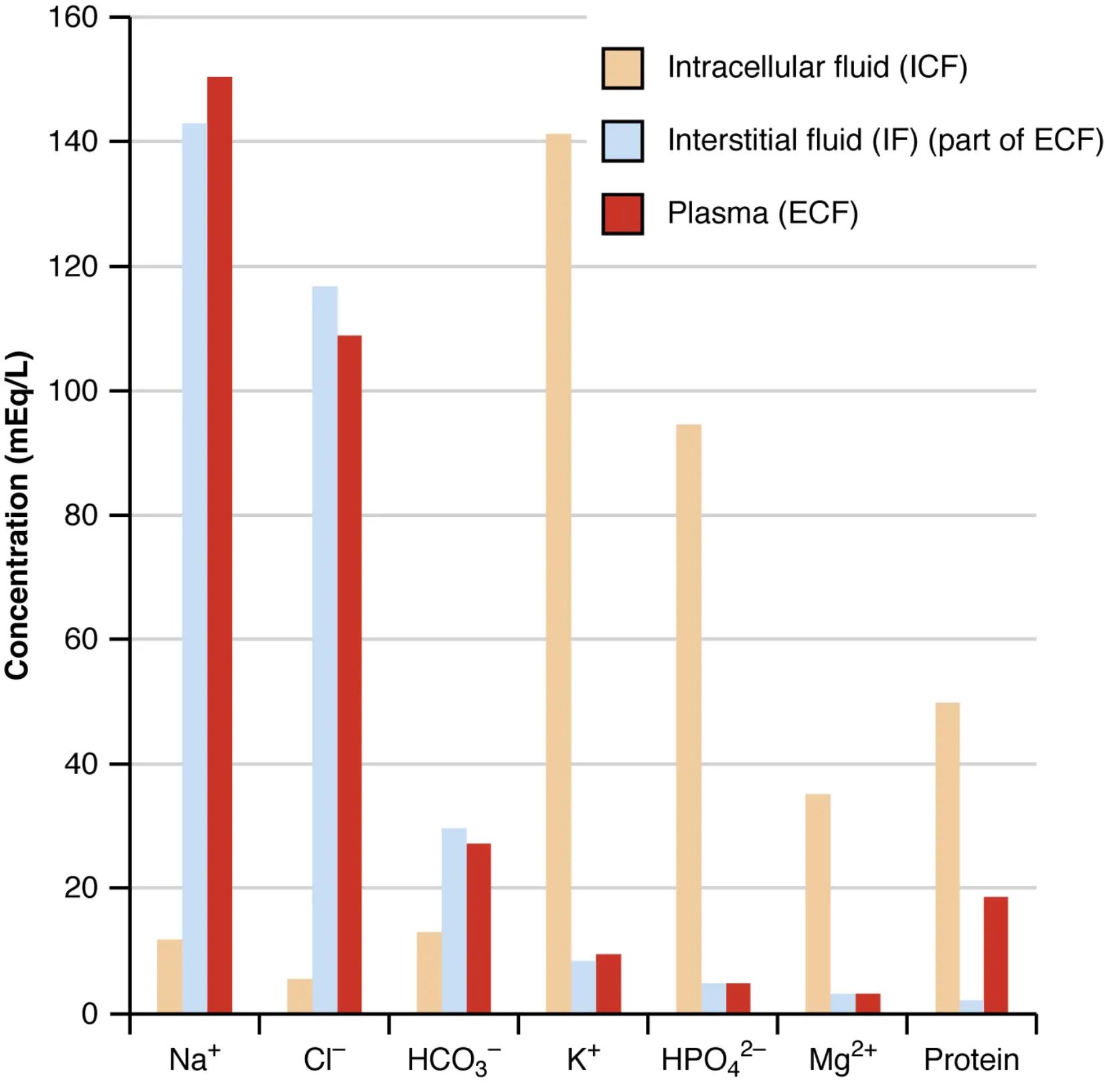

The precise regulation of fluid and electrolyte balance is a cornerstone of human physiology. This bar graph provides a clear comparative analysis of the concentrations of key elements, including major electrolytes and proteins, across the body’s primary fluid compartments: intracellular fluid (ICF), interstitial fluid (IF), and plasma. It strikingly illustrates the distinct biochemical environments maintained in each compartment, crucial for cellular function and systemic homeostasis. Understanding these differences is vital for diagnosing and managing conditions related to fluid and electrolyte disturbances.

Intracellular fluid (ICF): The fluid within cells.

The intracellular fluid (ICF) is characterized by high concentrations of potassium (K+), phosphate (HPO42-), and magnesium (Mg2+), along with a significant amount of protein. Conversely, it has low levels of sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl-). This unique ionic composition is meticulously maintained by the cell membrane, particularly through the action of the Na+/K+ pump, which actively transports ions to ensure proper cell volume, nerve impulse transmission, and muscle contraction.

Interstitial fluid (IF): Part of the extracellular fluid (ECF) between the cells.

Interstitial fluid (IF) closely mirrors the composition of plasma with a few key differences. It is rich in sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl-) and has moderate levels of bicarbonate (HCO3-). However, compared to plasma, IF has a significantly lower protein content, as large protein molecules typically do not easily cross capillary walls. This fluid serves as the immediate environment for cells, facilitating nutrient and waste exchange.

Plasma (ECF): The fluid component of blood, the second part of the ECF.

Plasma, the fluid portion of blood, is part of the extracellular fluid (ECF) and has a composition very similar to interstitial fluid, being high in sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl-) and having moderate bicarbonate (HCO3-). A defining characteristic of plasma, however, is its high concentration of proteins, which are largely retained within the intravascular space. These plasma proteins, such as albumin, are crucial for maintaining colloid osmotic pressure, blood viscosity, and transporting various substances.

The graphical representation vividly highlights the striking differences in electrolyte and protein concentrations between the intracellular fluid (ICF) and the two components of the extracellular fluid (ECF), namely the interstitial fluid (IF) and plasma. While plasma and IF share a similar ionic profile, primarily rich in sodium and chloride, the ICF stands apart with its high potassium and phosphate content, along with a substantial amount of intracellular proteins. This differential distribution is not arbitrary; it is meticulously regulated and fundamental to all cellular and systemic functions.

This precise compartmentalization is achieved through selectively permeable cell membranes and the active transport mechanisms embedded within them. For instance, the omnipresent sodium-potassium pump actively expels three Na+ ions for every two K+ ions it brings into the cell, maintaining the steep electrochemical gradients essential for:

- Nerve impulse transmission.

- Muscle contraction.

- Regulation of cell volume.

- Secondary active transport of other molecules.

The significant difference in protein concentration between plasma and interstitial fluid, with plasma having considerably more, is also critical. Plasma proteins exert colloid osmotic pressure, which is vital for drawing water back into the capillaries from the interstitial space, thereby maintaining blood volume and preventing excessive fluid accumulation in tissues (edema). Conversely, the low protein content in IF ensures that nutrients and gases can freely diffuse to and from cells without significant osmotic hindrance.

Understanding these concentration gradients is not merely an academic exercise; it is profoundly important in clinical practice. Imbalances in these electrolytes, such as hypernatremia, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, or hypokalemia, can profoundly affect nerve, muscle, and cardiac function, leading to a range of symptoms and potentially life-threatening conditions. Similarly, disorders affecting plasma protein levels can lead to significant fluid shifts and cardiovascular complications. This detailed insight into fluid composition forms the basis for diagnosing fluid and electrolyte disorders and guiding appropriate medical interventions.

In conclusion, this bar graph serves as a powerful illustration of the distinct biochemical landscapes within the body’s fluid compartments. The tightly controlled concentrations of electrolytes and proteins are not just characteristic features but active determinants of physiological function. A comprehensive grasp of these differences is indispensable for anyone seeking to understand the intricacies of human homeostasis, providing a critical foundation for clinical reasoning in fluid and electrolyte management.