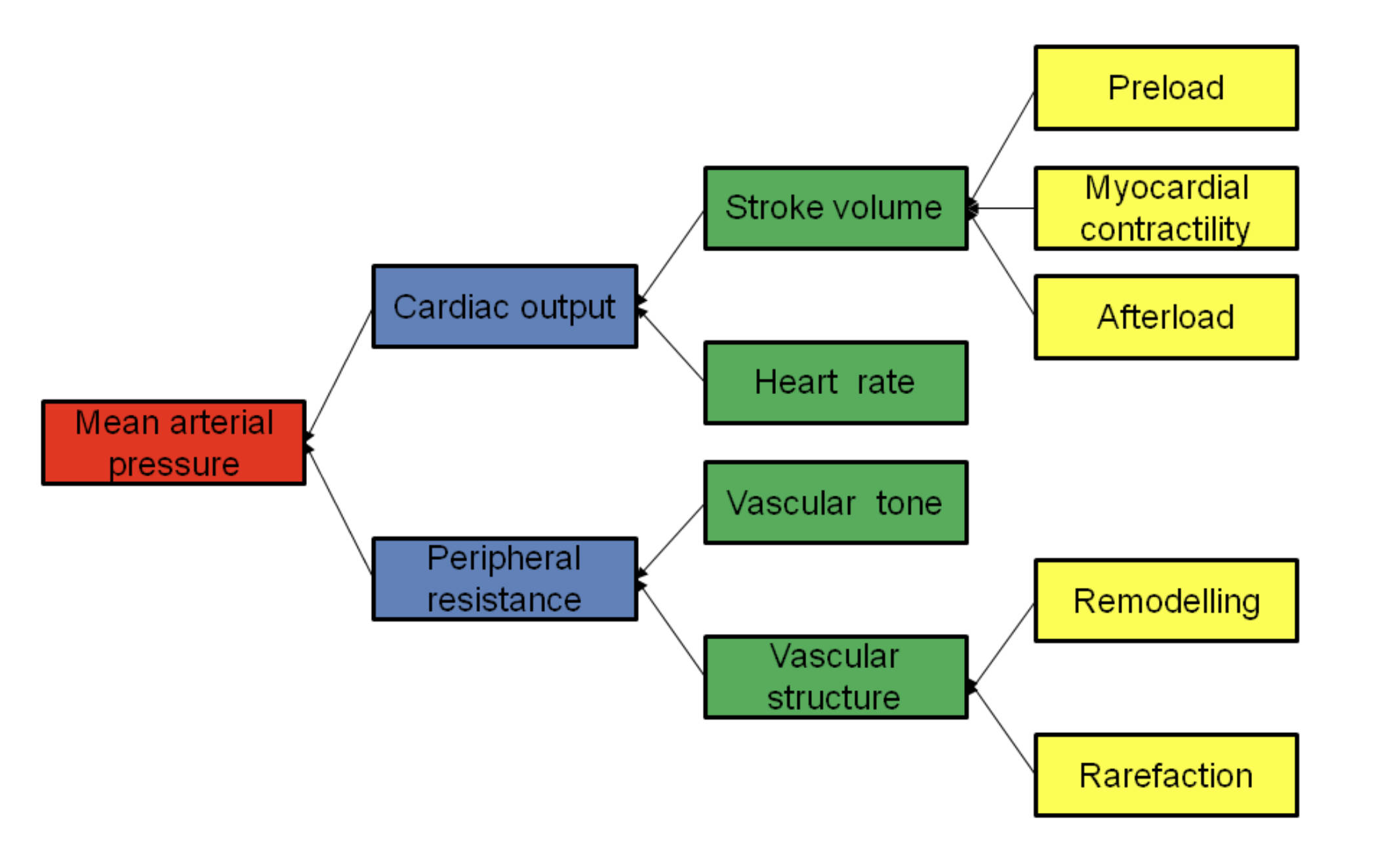

Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) is a critical indicator of perfusion to vital organs, representing the average arterial pressure during a single cardiac cycle. Understanding the physiological determinants that influence MAP—ranging from cardiac output and peripheral resistance to cellular-level remodelling—is essential for grasping cardiovascular hemodynamics and clinical patient management.

Mean arterial pressure: This is the average arterial pressure throughout one cardiac cycle, including both systole and diastole. It is considered a more reliable indicator of organ perfusion than systolic blood pressure alone, as it accounts for the longer duration of the diastolic phase.

Cardiac output: This represents the total volume of blood the heart pumps per minute, usually measured in liters. It is a primary factor in maintaining systemic blood pressure and ensuring that tissues receive adequate oxygenation.

Peripheral resistance: Also known as systemic vascular resistance, this refers to the friction or resistance that blood must overcome as it travels through the body’s network of vessels. It is largely determined by the diameter of small arteries and arterioles, which can constrict or dilate to regulate flow.

Stroke volume: This is the specific amount of blood ejected by the left ventricle of the heart during a single contraction. It is determined by the balance of fluid filling the heart, the strength of the muscle, and the resistance in the systemic circulation.

Heart rate: This is the number of times the heart beats per minute, typically measured as a pulse. Variations in heart rate allow the body to adjust cardiac output rapidly to meet the physical demands of exercise or stress.

Vascular tone: This refers to the degree of constriction or dilation experienced by a blood vessel relative to its maximally dilated state. It is regulated by the autonomic nervous system and local chemical signals to control the flow of blood to various organs.

Vascular structure: This encompasses the physical architecture of the blood vessel walls, including their thickness and elasticity. Changes in vascular structure can significantly alter how vessels respond to changes in pressure and flow over time.

Preload: This is the initial stretching of the cardiac myocytes (heart muscle cells) prior to contraction, often associated with ventricular filling at the end of diastole. According to the Frank-Starling law, an increase in preload leads to a stronger contraction and an increase in stroke volume.

Myocardial contractility: This is the intrinsic ability of the heart muscle to contract with a certain force regardless of the degree of stretch. It is influenced by sympathetic nervous system stimulation and is a key target for many cardiac medications.

Afterload: This represents the tension or “load” against which the left ventricle must exert itself to eject blood into the aorta. It is clinically approximated by systemic vascular resistance and the pressure within the large arteries.

Remodelling: This is a structural change in the blood vessel wall in response to chronic changes in hemodynamic conditions, such as long-term high blood pressure. Vascular remodelling often results in thicker, stiffer walls that can further exacerbate cardiovascular issues.

Rarefaction: This refers to a decrease in the anatomical density of small blood vessels, such as arterioles and capillaries, within a specific tissue. Rarefaction increases the overall resistance to blood flow and is a common finding in the progression of chronic vascular diseases.

The Physiological Regulation of Blood Pressure

The regulation of blood pressure is a complex, multi-layered process that ensures the brain, kidneys, and other vital organs receive a constant supply of blood. Mean arterial pressure is the central variable that the body works to maintain within a narrow physiological range through homeostatic mechanisms. When MAP falls too low, organs can suffer from ischemia; conversely, when it is chronically high, it leads to cumulative damage to the heart and arterial walls.

The hierarchy of blood pressure determinants shows how various biological systems interact. At the highest level, MAP is the product of how much blood the heart is pumping and how much the blood vessels resist that flow. Each of these branches further into mechanical and structural components that provide a comprehensive view of how the circulatory system functions under different conditions.

Key determinants that influence this hemodynamic balance include:

- Fluid volume and venous return, which dictate the stretch of the heart muscle.

- The autonomic nervous system’s influence on heart rate and vessel constriction.

- The physical elasticity and structure of the vessel walls.

- Local metabolic factors that trigger vessels to dilate during physical activity.

By analyzing these components, clinicians can pinpoint the underlying cause of blood pressure abnormalities. For instance, a patient with heart failure might have low MAP due to decreased myocardial contractility, whereas a patient with chronic metabolic issues might experience structural changes in their microvasculature that drive resistance upward.

Clinical Implications: Hypertension and Vascular Change

Since the determinants of MAP include factors like remodelling and rarefaction, they are deeply relevant to the study of hypertension (high blood pressure). Hypertension is a chronic medical condition where the arterial blood pressure is persistently elevated, often without obvious symptoms. Over time, this “silent killer” can lead to significant damage across the body’s vascular network.

In the context of the diagram, chronic hypertension often triggers a pathological feedback loop. Persistent high pressure causes the blood vessels to undergo remodelling, where the vessel walls thicken and lose elasticity to withstand the mechanical stress. This narrowing of the vessel lumen increases peripheral resistance, which in turn further elevates the mean arterial pressure. Additionally, rarefaction—the functional or anatomical loss of small vessels—compounds this issue by reducing the available pathways for blood flow, forcing the heart to work harder.

The heart must also adapt to these changes. To overcome the increased afterload caused by stiffened vessels and high peripheral resistance, the left ventricle may undergo hypertrophy (muscle thickening). While this adaptation helps maintain stroke volume in the short term, it eventually leads to decreased compliance and can progress to heart failure. Managing hypertension involves addressing these specific determinants, often through medications that reduce vascular tone or diuretics that decrease preload by reducing the body’s total blood volume.

The determinants of mean arterial pressure represent a delicate equilibrium between cardiac performance and vascular architecture. By understanding how preload, contractility, and afterload influence stroke volume, and how structural changes like remodelling affect peripheral resistance, we gain a clearer picture of human health and disease. Mastering these concepts is fundamental for anyone looking to understand the mechanics of the heart and the critical role of the vascular system in maintaining life and longevity.