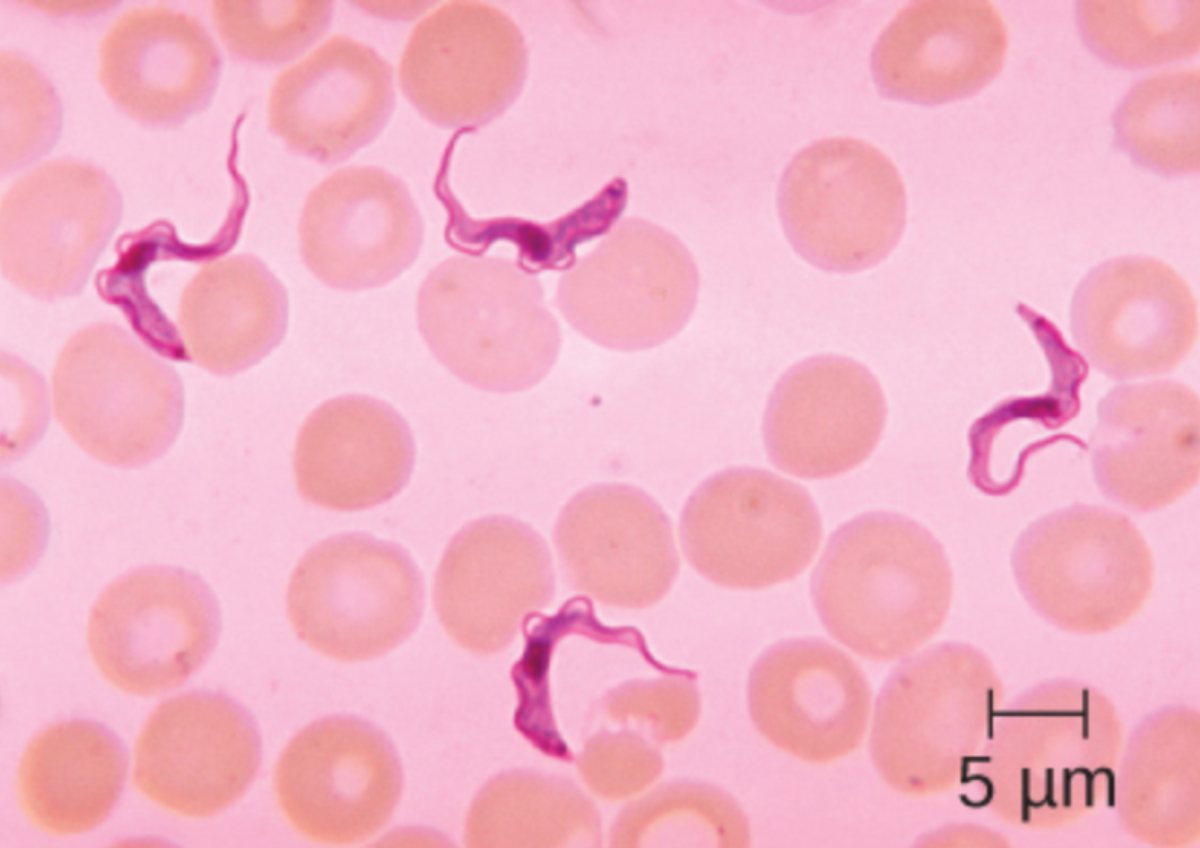

This comprehensive overview examines the unique fusiform morphology of Trypanosoma as seen in clinical blood smears. By understanding the anatomical features of these parasitic eukaryotes and the physiological progression of human African trypanosomiasis, medical professionals can improve diagnostic accuracy and patient outcomes in endemic regions.

5 μm: This label denotes a scale bar equivalent to five micrometers in length. It serves as a vital tool in microscopy to quantify the physical dimensions of the parasitic cells and red blood cells shown in the specimen.

Eukaryotic cells exhibit a wide variety of shapes, each adapted to their specific environment or biological role. While many human cells are spherical or cuboidal, certain organisms have evolved specialized morphologies to survive in challenging environments. One of the most striking examples is the genus Trypanosoma, which features a distinctive fusiform, or spindle-shaped, body that is narrowed at both ends.

These organisms are flagellated protozoans that live as parasites in the blood and tissues of various vertebrate hosts. Their sleek, streamlined shape allows them to move efficiently through the viscous medium of human blood. This movement is facilitated by a single flagellum and an undulating membrane that ripples along the length of the cell, providing a propeller-like mechanism for navigation through the dense population of erythrocytes.

Identifying these parasites is a critical step in tropical medicine. Under a microscope, using Giemsa or Wright stain, the Trypanosoma appear as vibrant, elongated purple structures amidst a field of pinkish biconcave erythrocytes. Understanding their unique anatomy is the first step in recognizing the signs of infection and initiating life-saving treatments.

- Fusiform (spindle-shaped) cell body optimized for fluid dynamics.

- Presence of a kinetoplast, a specialized DNA-containing mitochondrial structure.

- Single anterior flagellum connected to the body by an undulating membrane.

- Adaptation for extracellular life within the vertebrate host’s bloodstream.

The Anatomy of a Pathogen: Exploring Trypanosoma Morphology

The fusiform shape of Trypanosoma is not merely an aesthetic trait; it is a hydrodynamically optimized form that supports a high degree of parasitemia within the host. Measuring approximately 15 to 30 micrometers in length, these cells are larger than the surrounding red blood cells, which typically measure 7 to 8 micrometers. The cell’s structural integrity is maintained by a subpellicular cytoskeleton made of microtubules, which provides the rigidity necessary for its distinctive shape while allowing for the flexibility required to squeeze through narrow capillaries.

Inside the cell, the most notable feature is the kinetoplast. This is a dense mass of circular DNA (kDNA) located within the organism’s single large mitochondrion. The position of the kinetoplast relative to the nucleus and the base of the flagellum is used by parasitologists to identify different stages of the parasite’s life cycle. This unique organelle is a target for several antiparasitic drugs, as its function is essential for the parasite’s metabolic processes.

Clinical Manifestations of African Sleeping Sickness

Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT), commonly known as African Sleeping Sickness, is a severe vector-borne disease caused by the parasite Trypanosoma brucei. The disease is transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected tsetse fly (genus Glossina). There are two main forms: the chronic form caused by T. b. gambiense, which accounts for the majority of cases in West and Central Africa, and the acute form caused by T. b. rhodesiense found in Eastern and Southern Africa.

The clinical progression of the disease occurs in two distinct stages. The first stage, known as the hemolymphatic phase, is characterized by the parasite multiplying in the blood and lymph. Patients often present with non-specific symptoms such as intermittent fever, severe headaches, joint pain, and itching. Swollen lymph nodes along the back of the neck, known as Winterbottom’s sign, are a classic clinical finding during this phase.

The Neurological Challenge

As the disease progresses into the second stage, or the meningoencephalitic phase, the parasites cross the blood-brain barrier and invade the central nervous system. This leads to the hallmark symptoms of the disease: significant disruption of the sleep-wake cycle. Patients may experience daytime somnolence and nighttime insomnia, along with confusion, sensory disturbances, and poor coordination. Without prompt and effective medical intervention, the neurological damage becomes irreversible, eventually leading to coma and death.

The diagnosis of HAT relies heavily on the microscopic examination of blood smears, as shown in the provided image. Because the parasite load can fluctuate, repeated smears or concentration techniques are often necessary to confirm the presence of the fusiform organisms. Early detection is paramount, as the medications used to treat the second stage of the disease are generally more toxic and more difficult to administer than those used in the early stages.

The study of Trypanosoma highlights the complex relationship between cellular form and pathogenic function. From the specialized spindle shape that allows it to evade the host’s immune system to the devastating neurological impact of the infection, this parasite remains a significant challenge for global health. Continued research into the molecular biology and morphology of these eukaryotes is essential for developing new diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies to eradicate this debilitating disease.