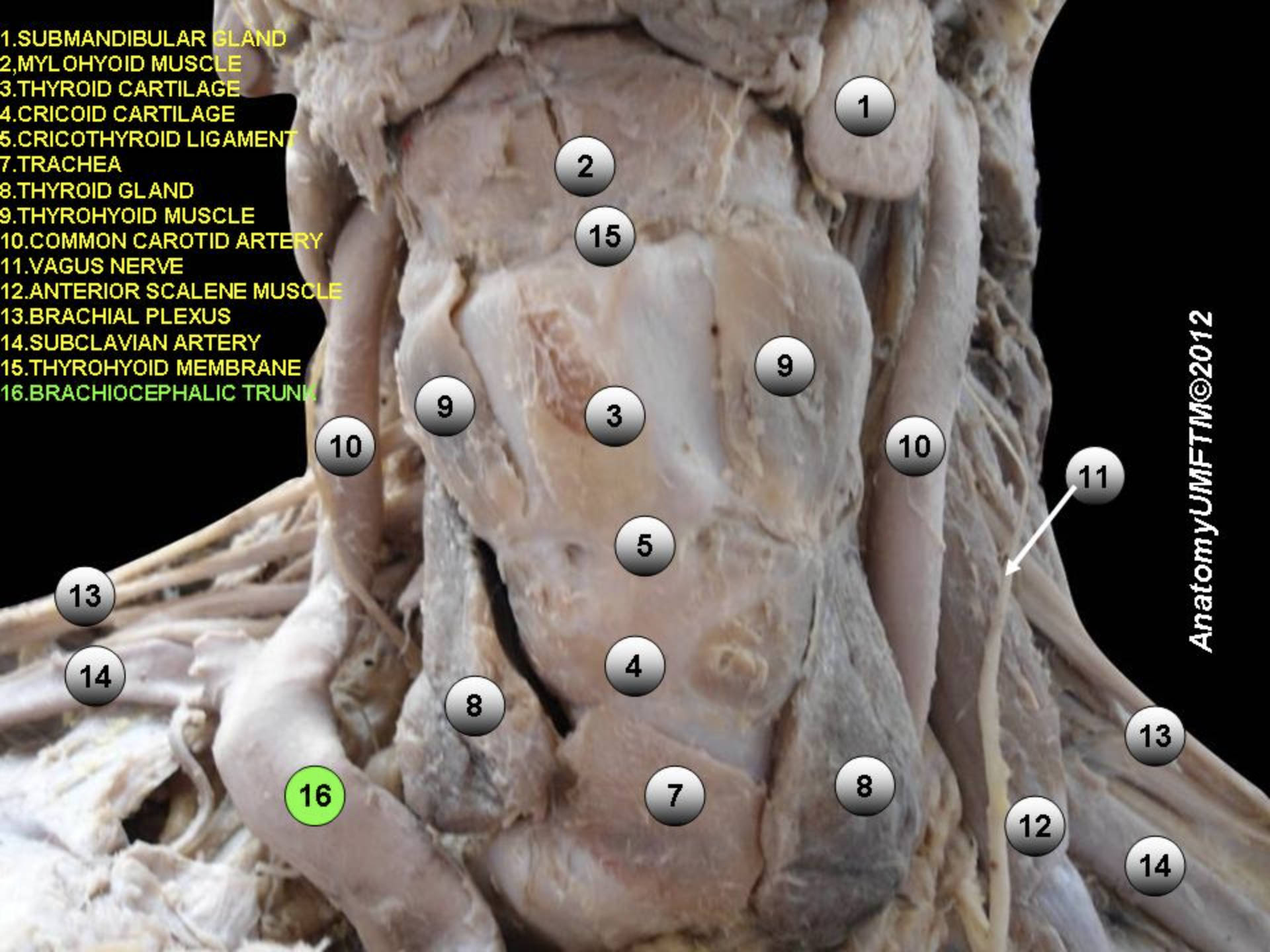

This anterior view of a cadaveric dissection provides a comprehensive look at the vital structures of the neck and upper thorax, specifically highlighting the course of the major vessels and the laryngeal skeleton. The image allows for a detailed study of the relationships between the respiratory tract, the endocrine system, and the complex neurovascular networks that supply the head, neck, and upper limbs. By examining these labeled structures, medical professionals and students can better understand the intricate spatial organization required for surgical interventions and clinical diagnostics in this region.

1. Submandibular Gland: This is one of the major paired salivary glands located beneath the floor of the mouth. It is responsible for producing a significant portion of saliva, which aids in lubrication and the initial digestion of food.

2. Mylohyoid Muscle: Forming the muscular floor of the oral cavity, this muscle runs from the mandible to the hyoid bone. It plays a crucial role in elevating the hyoid bone and the tongue during swallowing and speaking.

3. Thyroid Cartilage: Often referred to as the “Adam’s apple,” this is the largest cartilage of the larynx. It serves as a protective shield for the vocal cords and forms the anterior wall of the larynx.

4. Cricoid Cartilage: Located directly below the thyroid cartilage, this is the only complete ring of cartilage around the trachea. It helps maintain airway patency and serves as an attachment point for muscles involved in opening and closing the airway.

5. Cricothyroid Ligament: This membrane connects the thyroid cartilage to the cricoid cartilage below it. In emergency situations where the upper airway is obstructed, this site is used to perform a cricothyrotomy to establish an emergency airway.

7. Trachea: Commonly known as the windpipe, this cartilaginous tube extends from the larynx to the bronchial tubes. It is reinforced by C-shaped cartilage rings that prevent collapse, ensuring a clear pathway for air to reach the lungs.

8. Thyroid Gland: This butterfly-shaped endocrine gland wraps around the anterior portion of the trachea. It is responsible for secreting hormones such as thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), which regulate the body’s metabolic rate.

9. Thyrohyoid Muscle: This strap muscle of the neck belongs to the infrahyoid group. It functions to depress the hyoid bone or elevate the larynx, playing a coordinated role in the swallowing reflex.

10. Common Carotid Artery: This major blood vessel supplies oxygenated blood to the brain, neck, and face. It runs vertically within the carotid sheath and eventually bifurcates into the internal and external carotid arteries.

11. Vagus Nerve: Cranial Nerve X, seen here descending in the neck, is the longest cranial nerve in the body. It provides parasympathetic innervation to the heart, lungs, and digestive tract, regulating heart rate and peristalsis.

12. Anterior Scalene Muscle: Located deep in the neck, this muscle originates from the cervical vertebrae and attaches to the first rib. It acts as an accessory muscle of respiration by elevating the rib cage and serves as a critical anatomical landmark for the brachial plexus.

13. Brachial Plexus: This complex network of nerves originates from the ventral rami of spinal nerves C5 through T1. It is responsible for cutaneous and muscular innervation of the entire upper limb, including the shoulder, arm, and hand.

14. Subclavian Artery: This major artery travels under the clavicle (collarbone) to supply blood to the arms. In the image, it is seen emerging near the anterior scalene muscle before continuing as the axillary artery.

15. Thyrohyoid Membrane: This broad, fibro-elastic sheet connects the upper border of the thyroid cartilage to the hyoid bone. It is perforated by the internal laryngeal nerve and the superior laryngeal artery.

16. Brachiocephalic Trunk: Also known as the innominate artery, this is the first major branch of the aortic arch. It is a short but wide vessel that ascends briefly before dividing into the right common carotid and right subclavian arteries.

The Anatomy of the Anterior Neck and Superior Mediastinum

The anatomical region depicted in this dissection represents one of the most clinically significant areas of the human body, known as the anterior triangle of the neck and the superior thoracic aperture. This compact space serves as a conduit for essential systems: the respiratory tract via the trachea, the digestive tract via the esophagus (located posteriorly), and the central vascular supply to the brain. The organization of these structures is highly efficient; deeply seated structures like the trachea and thyroid gland are protected by layers of fascia and “strap muscles,” such as the thyrohyoid and sternothyroid.

Of particular importance in this image is the Brachiocephalic Artery (labeled as the Brachiocephalic Trunk), which is unique to the right side of the body. While the left common carotid and left subclavian arteries typically arise directly from the aortic arch, the right side relies on this single trunk to branch out. This asymmetry is a fundamental concept in vascular anatomy. The trunk ascends obliquely to the level of the right sternoclavicular joint, where it bifurcates. Understanding this branching pattern is critical for surgeons performing procedures in the superior mediastinum or anterior neck, as anatomical variations can occur.

Furthermore, the relationship between the vascular structures and the nervous system is clearly visible. The vagus nerve travels within the carotid sheath alongside the common carotid artery and internal jugular vein (though the vein is removed or collapsed in this preparation). Nearby, the brachial plexus emerges between the anterior and middle scalene muscles. This proximity means that pathology in one structure—such as an aneurysm of the subclavian artery or a tumor in the lung apex—can easily compress the nerves, leading to symptoms in the arm or changes in heart rate regulation.

Key functional roles of the structures in this region include:

- Airway Protection and Phonation: The cartilaginous framework of the larynx (thyroid and cricoid cartilages) protects the vocal cords.

- Endocrine Regulation: The thyroid gland controls metabolism and calcium homeostasis.

- Hemodynamics: The major arteries transport high-pressure, oxygenated blood to the brain and upper extremities.

- Neuromuscular Control: The brachial plexus and vagus nerve facilitate movement and autonomic regulation.

Physiological Significance of the Neck Neurovasculature

The physiology of the neck is defined by its role as a bridge between the body’s command center—the brain—and the rest of the organism. The Common Carotid Artery, visible on both sides of the trachea, is the primary source of cerebral blood flow. It carries blood under significant pressure; therefore, the body has developed baroreceptors located at the carotid bifurcation (the carotid sinus) to monitor blood pressure constantly. If pressure drops or spikes, these receptors signal the brainstem via the glossopharyngeal nerve to adjust heart rate and vessel diameter, showcasing the tight integration of these anatomical structures.

Adjacent to the vascular system is the brachial plexus, a vital neural highway. As seen in the dissection, the nerves pass between the scalene muscles. This specific anatomical passage is clinically relevant in conditions like Thoracic Outlet Syndrome, where the nerves or the subclavian artery become compressed in this narrow space. This can lead to pain, numbness, and vascular insufficiency in the arm. The image highlights how crowded this region is, emphasizing why even minor anatomical deviations or inflammation can result in significant functional impairment.

Finally, the presence of the thyroid gland highlights the metabolic importance of this region. This gland is highly vascularized, receiving blood from the superior and inferior thyroid arteries. It extracts iodine from the blood to synthesize hormones that influence almost every tissue in the body. In surgical contexts, such as a thyroidectomy, the surgeon must be meticulously careful to avoid damaging the nearby recurrent laryngeal nerve (a branch of the vagus nerve) or the parathyroid glands, illustrating the high stakes of anatomy in the anterior neck.

In conclusion, this cadaveric specimen offers a clear window into the dense anatomical landscape of the human neck. From the structural support of the tracheal cartilages to the hemodynamic pathways of the brachiocephalic and subclavian arteries, each labeled part plays a distinct yet interconnected role in human physiology. Mastery of these relationships is essential for medical practice, ensuring safe surgical approaches and accurate physical examinations of the neck and thorax.

brachiocephalic trunk, common carotid artery, thyroid gland anatomy, anterior scalene muscle, brachial plexus nerves, subclavian artery, vagus nerve function, cricothyroid ligament, trachea anatomy, submandibular gland, mylohyoid muscle, laryngeal cartilages, superior mediastinum, human neck dissection, thoracic outlet anatomy