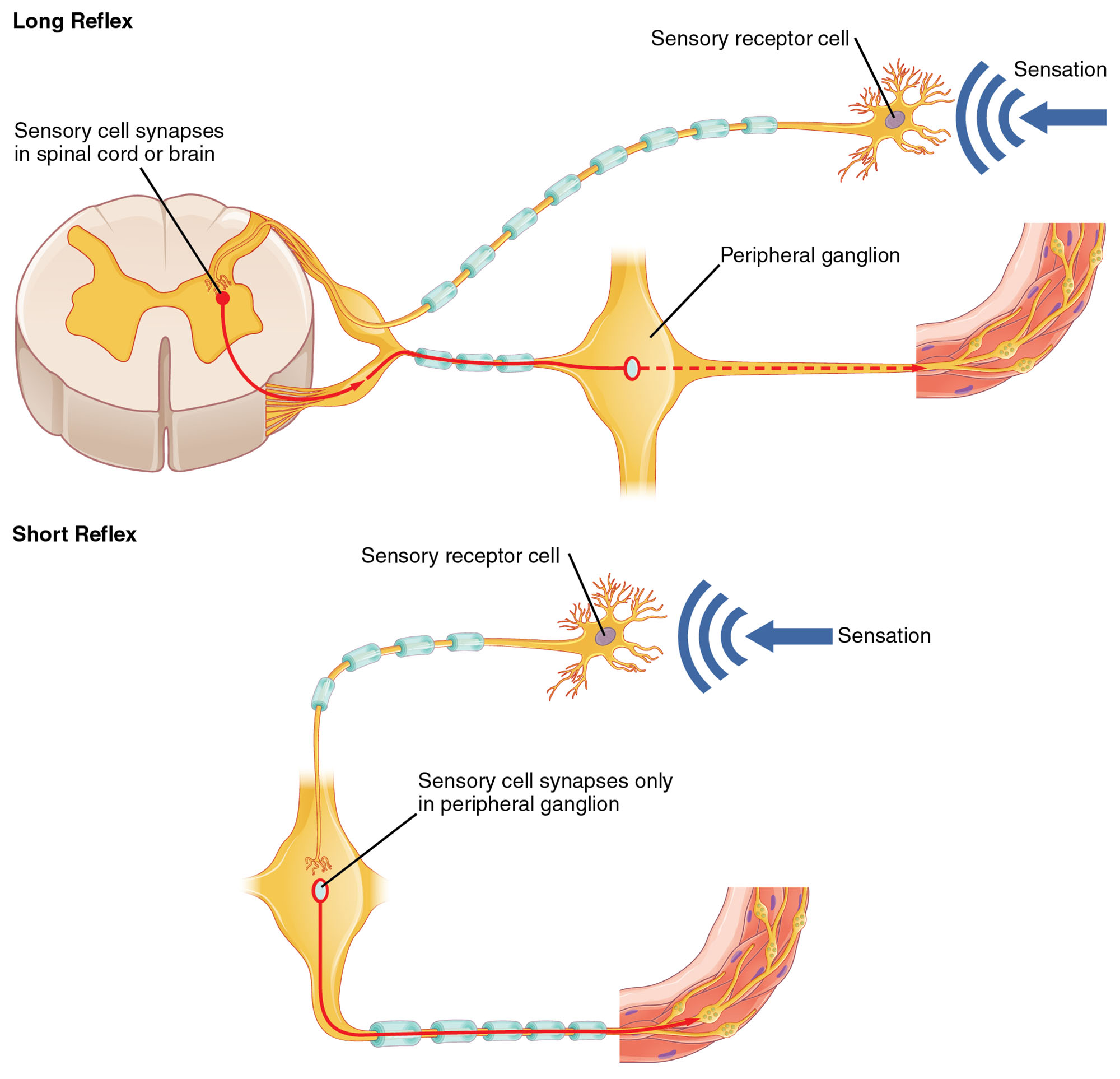

The diagram of short and long reflexes offers a clear window into how the nervous system orchestrates rapid responses to sensory input, highlighting the distinction between localized and integrated reactions. These reflexes, involving sensory neurons and either peripheral ganglia or the central nervous system, are fundamental to maintaining bodily functions and protecting against harm. Exploring this chart provides a deeper understanding of the intricate neural pathways that govern involuntary actions and their clinical relevance.

Labeled Components in the Diagram

Sensory receptor cell The sensory receptor cell detects environmental changes, such as touch or pressure, and converts these stimuli into electrical signals. These cells initiate the reflex arc by transmitting sensations to the nervous system for processing.

Sensation The sensation represents the conscious or unconscious perception of stimuli, indicated by the signal arrow in the diagram. This perception can trigger a reflex response, varying based on the reflex type and integration level.

Sensory cell synapses in spinal cord or brain The sensory cell synapses in spinal cord or brain mark the point where sensory input integrates with interneurons for a long reflex. This synapse allows for complex processing and coordination with higher brain centers.

Peripheral ganglion The peripheral ganglion serves as a relay station in the long reflex, housing cell bodies of postganglionic neurons. It facilitates signal transmission to effector organs without central nervous system involvement in short reflexes.

Sensory cell synapses only in peripheral ganglion The sensory cell synapses only in peripheral ganglion defines the short reflex pathway, where the sensory neuron directly connects to a postganglionic neuron. This direct connection enables quicker responses to local stimuli.

Anatomy of Reflex Pathways

Reflexes are automatic responses that protect the body from harm and maintain homeostasis. The distinction between short and long reflexes lies in their neural circuitry and processing speed.

- Short reflexes involve a simpler, two-neuron arc, bypassing the spinal cord or brain for rapid local responses.

- Long reflexes incorporate the central nervous system, allowing for more complex integration and modulation.

- Sensory neurons transmit signals via myelinated axons to enhance conduction velocity.

- The spinal cord contains gray matter where interneurons connect sensory and motor neurons in long reflexes.

- Peripheral ganglia, part of the autonomic nervous system, house cell bodies for short reflex effectors.

- Effector organs, such as smooth muscles or glands, respond to these neural signals.

Physiological Mechanisms of Reflexes

The physiological basis of reflexes involves rapid signal transmission and effector activation. This process ensures timely responses to potentially harmful stimuli or internal changes.

- Sensory receptors generate action potentials when stimulated beyond their threshold.

- In short reflexes, the sensory neuron synapses directly with a postganglionic neuron, releasing acetylcholine.

- Long reflexes involve interneurons that modulate the response based on brain input, using neurotransmitters like glutamate.

- Myelination of axons increases signal speed, critical for reflexes like the knee-jerk response.

- The reflex arc concludes with muscle contraction or glandular secretion, mediated by motor neurons.

- Feedback loops can adjust reflex strength, preventing overreaction to stimuli.

Differences Between Short and Long Reflexes

Short and long reflexes serve distinct purposes based on their anatomical pathways. Their differences impact response time and complexity of action.

- Short reflexes are confined to the enteric or autonomic ganglia, ideal for localized gut movements.

- Long reflexes extend to the spinal cord or brain, enabling coordinated responses like withdrawing from heat.

- The absence of central integration in short reflexes reduces latency, often under 50 milliseconds.

- Long reflexes allow for learning and adaptation, as seen in conditioned reflexes.

- Sensory input in short reflexes is processed by a single synapse, minimizing delay.

- Central processing in long reflexes can involve multiple synapses, enhancing precision.

Clinical Relevance of Reflex Pathways

Understanding reflex pathways aids in diagnosing neurological conditions and assessing nervous system integrity. These insights are crucial for effective clinical interventions.

- Exaggerated reflexes may indicate upper motor neuron lesions, such as in multiple sclerosis.

- Absent reflexes can suggest peripheral nerve damage, like in diabetic neuropathy.

- The Babinski sign, a long reflex variation, helps diagnose pyramidal tract issues.

- Short reflex disruptions in the gut can lead to motility disorders like ileus.

- Reflex testing, such as the patellar reflex, evaluates spinal cord function.

- Therapeutic approaches may target reflex arcs to manage spasticity or incontinence.

Role in Autonomic Function

Reflexes play a key role in autonomic regulation, particularly in the gastrointestinal and cardiovascular systems. This regulation maintains internal balance without conscious effort.

- Short reflexes control local enteric responses, such as peristalsis in the intestines.

- Long reflexes adjust heart rate via baroreceptor input to the medulla oblongata.

- The vagus nerve mediates long reflex parasympathetic effects on heart and lungs.

- Sympathetic short reflexes can trigger local vasoconstriction in response to injury.

- Integration in the hypothalamus fine-tunes long reflex responses to stress.

- These pathways ensure rapid adaptation to changing physiological demands.

Advances in Reflex Research

Ongoing research enhances our understanding of reflex mechanisms and their therapeutic potential. Innovations in this field promise improved neurological care.

- Optogenetics allows precise manipulation of reflex circuits in animal models.

- Neuroimaging tracks reflex activation in real-time, aiding diagnostic accuracy.

- Bioelectronic devices stimulate reflex pathways to treat chronic pain.

- Gene therapy explores repairing damaged reflex arcs in spinal injuries.

- Computational models simulate reflex responses for training and prediction.

- Clinical trials test neuromodulation to enhance reflex recovery post-stroke.

The study of short and long reflexes reveals the elegance of the nervous system’s protective and regulatory roles. By mastering these pathways, professionals can better diagnose and treat a range of conditions, fostering improved health outcomes through a deeper appreciation of neural responsiveness.