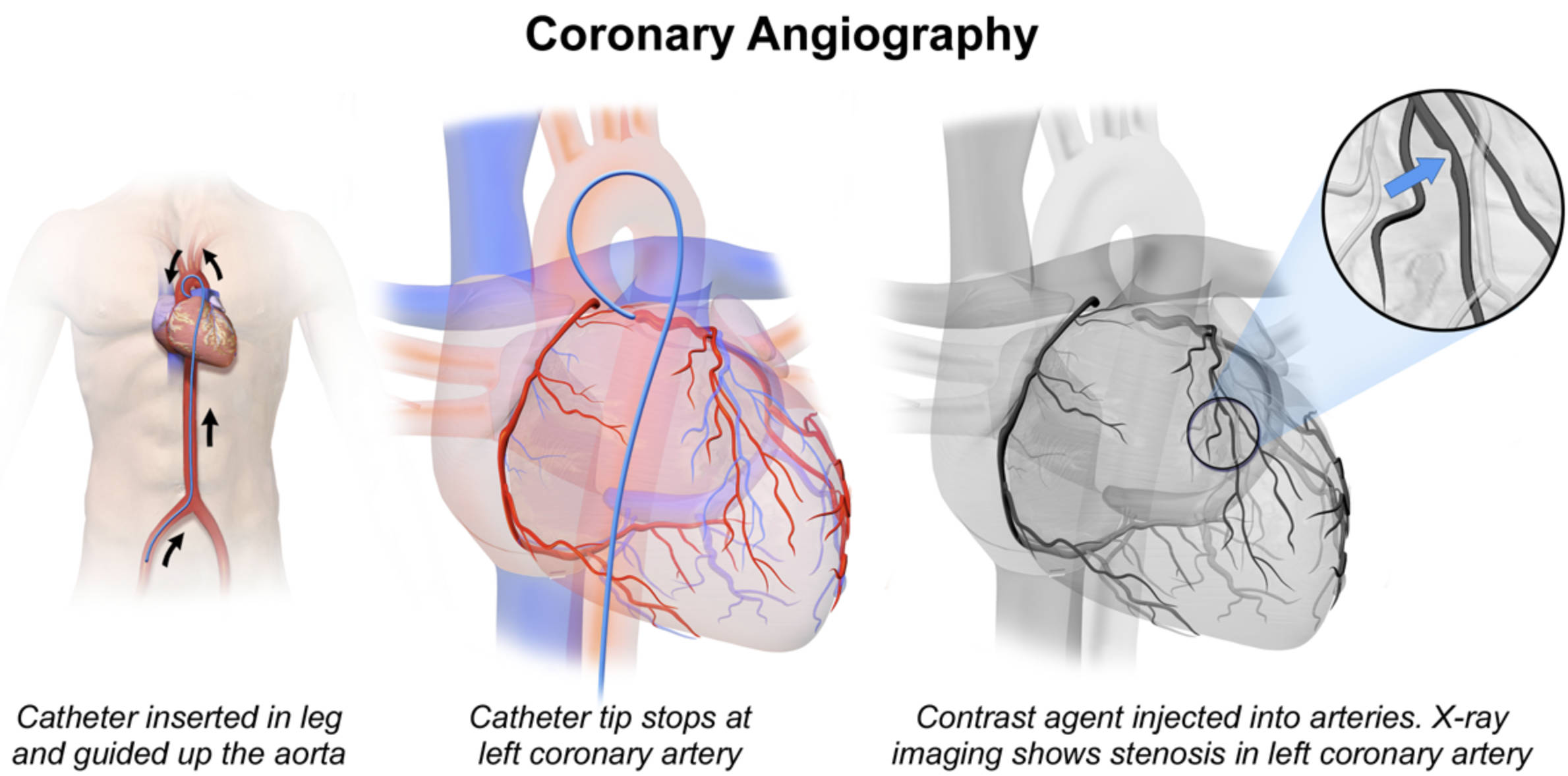

This diagram clearly illustrates the process of coronary angiography, a crucial diagnostic procedure used to visualize the arteries that supply blood to the heart. From catheter insertion to the final X-ray imaging, the sequence demonstrates how medical professionals identify blockages or narrowings, such as a stenosis in the left coronary artery. Understanding each step, as depicted, is essential for comprehending how this invasive technique precisely diagnoses coronary artery disease and guides subsequent treatment decisions.

Catheter inserted in leg and guided up the aorta: This label describes the initial step of the procedure, where a thin, flexible tube called a catheter is inserted into an artery, typically in the groin (femoral artery) or wrist (radial artery). The catheter is then carefully advanced through the patient’s arterial system, navigating its way up the aorta towards the heart. This precise guidance ensures the catheter reaches its target destination without causing damage.

Catheter tip stops at left coronary artery: This indicates the successful positioning of the catheter tip at the ostium (opening) of the left coronary artery. Once the catheter is correctly seated, it is ready for the injection of a contrast agent. This precise placement is critical to ensure that the dye flows directly into the coronary artery for optimal visualization.

Contrast agent injected into arteries. X-ray imaging shows stenosis in left coronary artery: This final step shows the injection of a radiographic contrast agent, which makes the coronary arteries visible under X-ray fluoroscopy. The resulting images clearly reveal a stenosis (narrowing) in the left coronary artery, as highlighted by the blue arrow in the magnified view. This narrowing is a key indicator of coronary artery disease and necessitates further medical attention.

Introduction to Coronary Angiography

Coronary angiography is an invaluable diagnostic tool in modern cardiology, offering a detailed, real-time view of the coronary arteries. These arteries are vital as they supply oxygen-rich blood to the heart muscle. When patients experience symptoms suggestive of coronary artery disease (CAD), such as chest pain (angina), shortness of breath, or abnormal stress test results, coronary angiography is often performed to confirm the diagnosis, precisely locate any blockages, and assess their severity. The accompanying diagram meticulously breaks down the procedure into its key stages, from catheter insertion to the visualization of arterial stenoses, providing a clear understanding of this invasive yet crucial test.

The procedure involves the use of X-rays and a special contrast dye. By injecting this dye directly into the coronary arteries, medical professionals can see how blood flows through them and identify any areas where plaque buildup has caused narrowing or complete obstruction. This detailed visualization is critical for making informed decisions about treatment, which could range from medication and lifestyle changes to interventional procedures like angioplasty, stenting, or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. The insights gained from an angiogram are fundamental to developing an effective, personalized treatment plan for patients with heart conditions.

Coronary angiography is typically performed in a cardiac catheterization laboratory by an interventional cardiologist. While it is an invasive procedure, it is generally safe when performed by experienced personnel, and the benefits of accurate diagnosis often outweigh the risks. Understanding the steps involved in an angiogram can help patients feel more prepared and informed about their cardiac care.

Key reasons a coronary angiogram may be recommended include:

- Unexplained chest pain (angina): Especially if severe or worsening.

- Symptoms of a heart attack (myocardial infarction): To identify the blocked artery needing urgent intervention.

- Abnormal results on non-invasive cardiac tests: Such as stress tests or nuclear scans.

- New or worsening heart failure symptoms: To assess if CAD is the underlying cause.

- Before certain cardiac surgeries: Like heart valve replacement, to check for concurrent CAD.

- Evaluation of previous coronary interventions: To check patency of stents or bypass grafts.

These indications highlight the procedure’s role in both acute and chronic cardiac management.

The Pathophysiology of Coronary Artery Disease and Stenosis

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is predominantly caused by atherosclerosis, a progressive condition where fatty deposits, cholesterol, calcium, and other substances accumulate to form plaques within the inner lining of the coronary arteries. This process can be accelerated by risk factors such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, smoking, and a family history of heart disease. As these plaques grow, they cause the artery to narrow, a condition known as stenosis, which is clearly depicted in the magnified view of the diagram.

This narrowing restricts the flow of oxygenated blood to the heart muscle (myocardium). When the heart muscle does not receive enough oxygen, it experiences ischemia, which can manifest as angina or, in severe cases, a heart attack. A critical stenosis can significantly compromise heart function and, if left untreated, can lead to irreversible damage or even sudden cardiac death. Coronary angiography precisely identifies these stenoses, allowing clinicians to quantify the degree of narrowing and determine the extent of myocardial compromise, which is essential for guiding therapeutic interventions.

The Coronary Angiography Procedure: Step-by-Step

The coronary angiography procedure, as clearly broken down in the diagram, follows a precise sequence:

- Catheter Insertion: The procedure begins with the patient receiving local anesthesia at the insertion site, typically the femoral artery in the groin or the radial artery in the wrist. A small incision is made, and a sheath (a thin, hollow tube) is inserted into the artery. A thin, flexible catheter is then introduced through the sheath.

- Catheter Guidance: Under continuous X-ray guidance (fluoroscopy), the cardiologist meticulously threads the catheter through the arterial system, navigating it up the aorta until its tip reaches the ostium (opening) of either the left or right coronary artery. The second panel of the diagram vividly shows the catheter tip precisely positioned at the left coronary artery.

- Contrast Agent Injection and Imaging: Once the catheter is correctly seated, a small amount of iodinated contrast agent (dye) is injected directly into the coronary artery. The contrast agent is opaque to X-rays, making the internal lumen of the artery visible. As the dye flows, rapid X-ray images (fluoroscopic sequences) are captured from various angles. The third panel, with its magnified view, clearly demonstrates how this X-ray imaging reveals a significant stenosis within the left coronary artery, as indicated by the blue arrow.

- Identification of Stenoses: The X-ray images allow the cardiologist to assess the patency of the arteries, identify any narrowings or blockages, determine their location, and estimate their severity (the degree of stenosis). This information is crucial for diagnosis and treatment planning.

After the procedure, the catheter is removed, and pressure is applied to the insertion site to prevent bleeding. Patients are typically monitored for several hours before discharge.

Post-Angiography: Treatment and Follow-Up

Based on the findings of the coronary angiogram, a treatment plan is formulated. If no significant blockages are found, the patient may be managed with medication and lifestyle modifications to control risk factors. However, if significant stenoses, like the one depicted, are identified, further interventions may be necessary:

- Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI): Often performed immediately after diagnostic angiography, PCI involves advancing a balloon-tipped catheter to the site of the stenosis. The balloon is inflated to open the narrowed artery, and a stent (a small mesh tube) is typically placed to keep the artery open.

- Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) Surgery: For more complex or extensive multi-vessel disease, CABG surgery may be recommended. This involves creating new pathways for blood to flow around the blocked arteries using grafts from other parts of the body.

- Medical Management: In some cases, even with mild-to-moderate stenoses, aggressive medical therapy with antiplatelet agents, statins, and blood pressure medications may be the primary treatment strategy.

Regardless of the intervention, long-term follow-up and rigorous management of cardiovascular risk factors are crucial to prevent the progression of atherosclerosis and ensure optimal patient outcomes. Regular check-ups and adherence to prescribed medications and lifestyle changes are essential for maintaining heart health after a coronary angiogram.