Prokaryotic cells represent one of the most resilient and diverse forms of life on Earth, encompassing the domains of Bacteria and Archaea. Unlike eukaryotic cells, which contain complex membrane-bound organelles and a defined nucleus, prokaryotes are characterized by a streamlined internal structure that allows for rapid growth and adaptation. Understanding the fundamental components of these organisms is essential for medical professionals and students alike, as these structures are often the primary targets for antibiotic treatments and play a pivotal role in the virulence factors that determine the severity of bacterial infections.

Structural Components of the Bacterial Cell

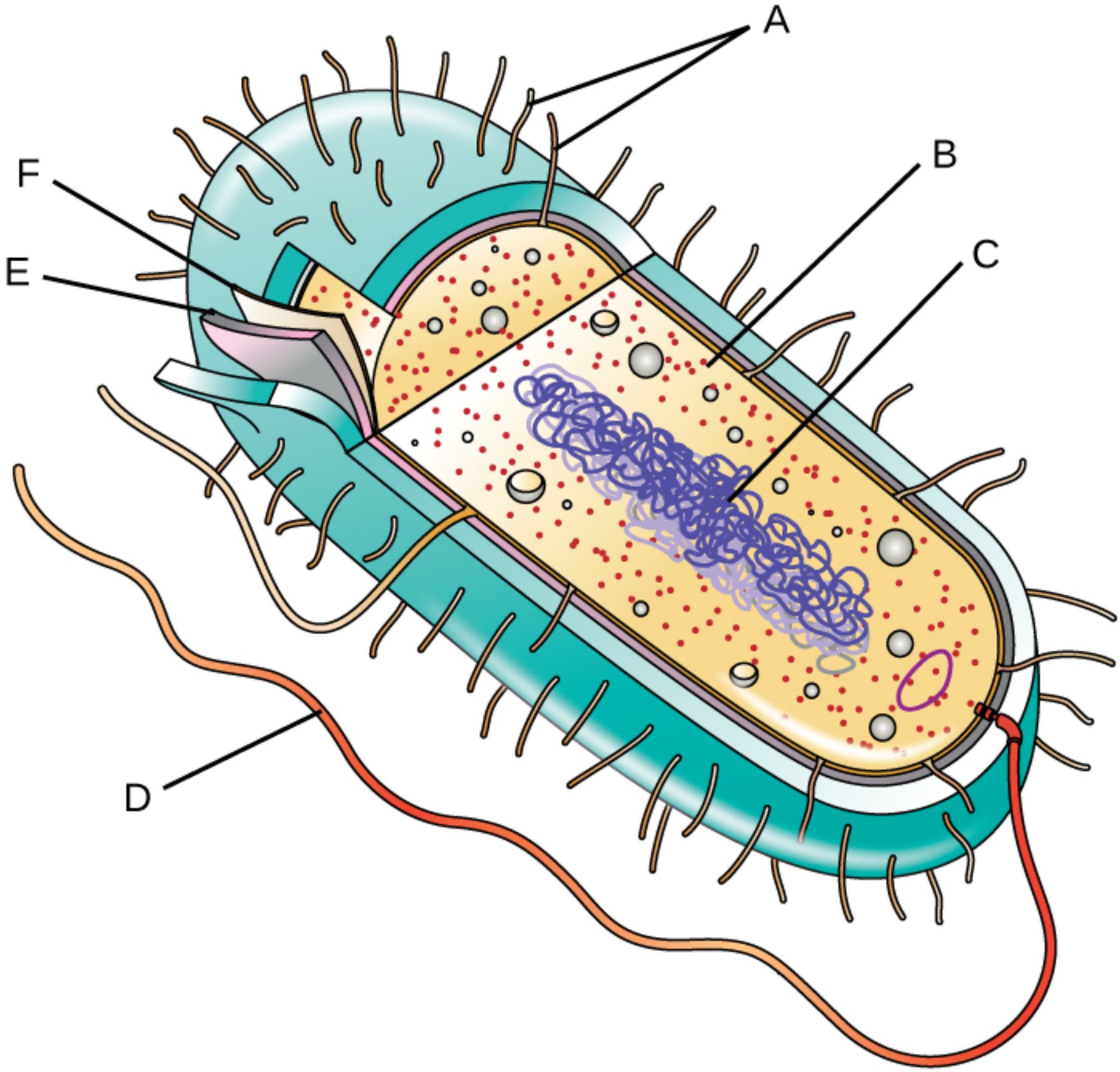

A – Pili: These hair-like appendages, also known as fimbriae, project from the cell surface to enable the bacterium to adhere to host tissues or inanimate surfaces. Specialized versions known as sex pili facilitate the transfer of genetic material between cells through conjugation, a process vital for the spread of antibiotic resistance.

B – Ribosomes: These granular structures serve as the molecular workstations for protein synthesis, translating messenger RNA into polypeptide chains within the cytoplasm. Bacterial ribosomes are designated as 70S, and their structural differences from human 80S ribosomes make them an ideal target for various antimicrobial therapies that inhibit protein production.

C – Nucleoid: This central, irregularly shaped region contains the primary genetic blueprint of the cell in the form of a large, circular DNA molecule. Because prokaryotes lack a nuclear envelope, this genetic material is suspended directly within the cellular fluid, allowing for rapid transcription and translation processes to occur simultaneously.

D – Flagellum: This complex, whip-like appendage acts as a biological motor to provide the cell with motility. By rotating in a propeller-like motion, the flagellum allows bacteria to navigate their environment through chemotaxis, moving purposefully toward favorable stimuli like nutrients or away from harmful chemicals.

E – Plasma Membrane: This delicate phospholipid bilayer acts as a selective gatekeeper, controlling the influx of essential nutrients and the efflux of metabolic waste products. It also plays a crucial role in energy production, as it contains the electron transport chain components necessary for generating ATP in the absence of specialized mitochondria.

F – Cell Wall: This robust outer layer provides the necessary structural support to maintain the cell’s shape and prevent lysis due to osmotic pressure. It is primarily composed of peptidoglycan, a unique polymer that distinguishes bacterial cells from eukaryotic hosts and serves as the primary site of action for beta-lactam antibiotics like penicillin.

The Biological Foundation of Prokaryotes

The simplicity of prokaryotic architecture is deceptively efficient, allowing these organisms to colonize nearly every niche on the planet, from deep-sea hydrothermal vents to the human gut microbiome. Because they lack internal compartmentalization, all biochemical reactions occur within the single cytoplasmic space. This lack of complexity is not a disadvantage; rather, it facilitates an incredibly high surface-area-to-volume ratio, which promotes the rapid exchange of nutrients and allows for lightning-fast metabolic responses to environmental changes.

Genetically, prokaryotes are masters of adaptation. While the nucleoid houses the essential chromosomal DNA, many bacteria also carry small, independent loops of DNA called plasmids. These plasmids often encode supplemental traits, such as toxin production or resistance to heavy metals and antibiotics. The ability to share these plasmids horizontally across a population means that a beneficial mutation in one bacterium can quickly become a dominant trait in an entire colony, presenting significant challenges in clinical settings.

The lifecycle of a prokaryote is centered on the process of binary fission, a form of asexual reproduction where a single cell duplicates its genetic material and divides into two identical daughter cells. Under optimal conditions, some bacterial species can double their population every twenty minutes, leading to exponential growth that can quickly overwhelm a host’s immune system if left unchecked.

Fundamental characteristics of prokaryotic life include:

- Lack of a membrane-bound nucleus or organelles like mitochondria and chloroplasts.

- Highly specialized cell envelopes that provide protection in hostile environments.

- A diverse range of metabolic pathways, including aerobic respiration, fermentation, and photosynthesis.

- The use of flagella and pili for environmental interaction and movement.

Clinical Relevance and Therapeutic Targets

From a medical perspective, the unique anatomy of the prokaryotic cell is its greatest vulnerability. Modern pharmacology exploits the structural differences between human and bacterial cells to create “magic bullets”—drugs that can eliminate pathogens without harming the patient. For instance, because human cells lack a cell wall, antibiotics that inhibit peptidoglycan synthesis can effectively kill bacteria without interfering with human tissue. Similarly, the structural distinctness of the bacterial 70S ribosome allows tetracyclines and macrolides to halt bacterial growth while leaving human protein synthesis intact.

However, the same structures that we target are also the tools bacteria use to defend themselves. The bacterial capsule, which sits outside the cell wall, can act as a “cloak” that helps the pathogen evade detection by the host’s white blood cells. Furthermore, the development of efflux pumps within the plasma membrane allows some bacteria to actively pump out antibiotic molecules before they can reach their targets. Continuous study of these microscopic structures remains a cornerstone of infectious disease research and the development of next-generation medical therapies.

In conclusion, the prokaryotic cell is a marvel of biological engineering, balancing simplicity with an extraordinary capacity for survival and reproduction. By examining each component—from the protective cell wall to the motile flagellum—we gain a clearer picture of how these organisms function both as essential members of our ecosystem and as formidable human pathogens. This anatomical knowledge is the bedrock upon which we build our understanding of microbiology, pathology, and the ongoing battle against antibiotic resistance.