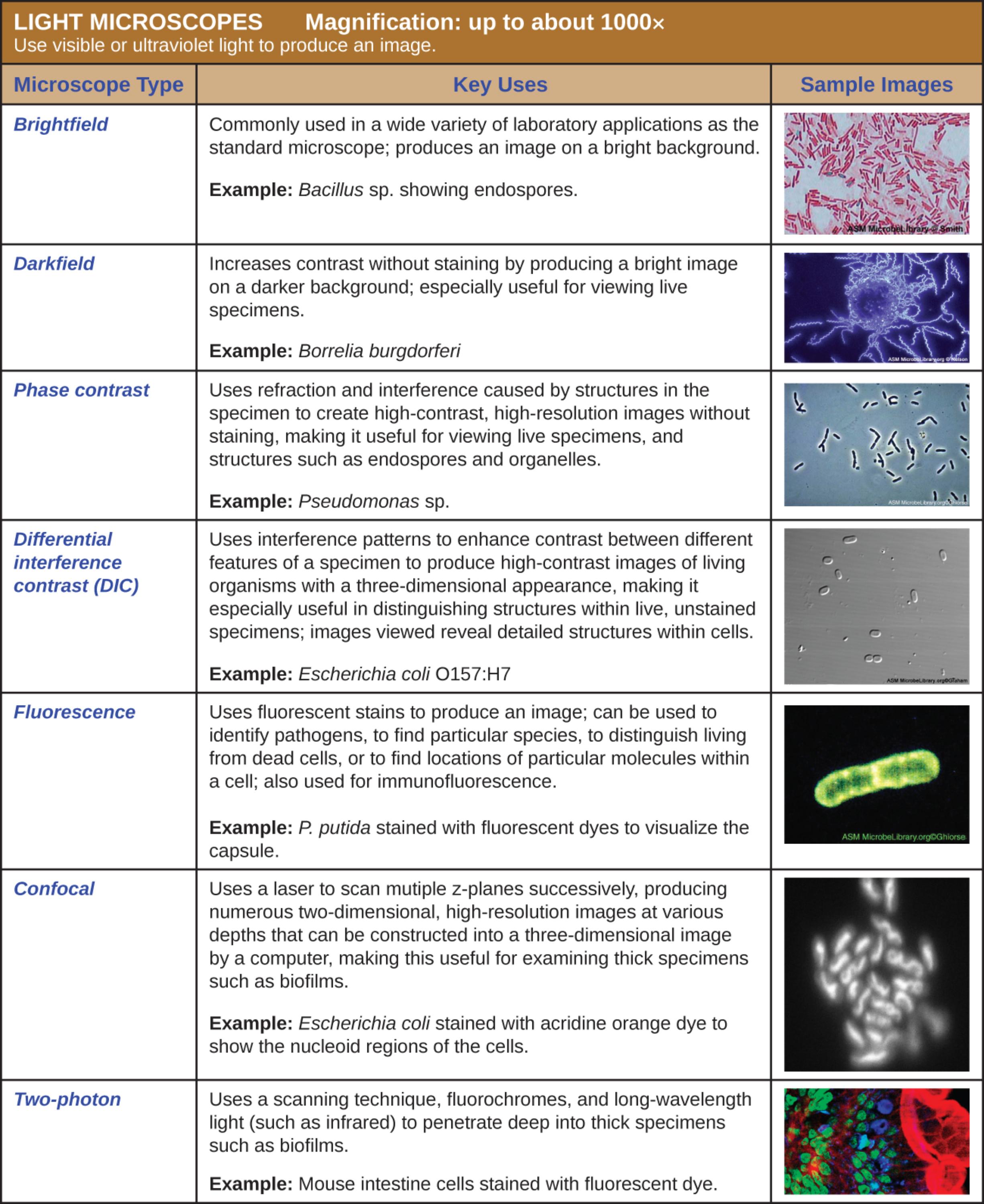

Microscopy plays a pivotal role in modern medicine and biological research, allowing scientists and clinicians to visualize the intricate details of the microscopic world that remains invisible to the naked eye. This guide explores the various types of light microscopy, ranging from standard brightfield techniques to advanced confocal and two-photon imaging, detailing how each method utilizes visible or ultraviolet light to produce magnifications up to 1000x. By understanding the specific applications of these instruments, medical professionals can better identify pathogens, examine cellular structures, and diagnose complex diseases with high precision.

Brightfield: This is the most standard form of light microscopy found in general laboratories, where visible light is transmitted through the specimen to produce an image on a bright background. It is commonly used for viewing fixed and stained specimens, such as the Bacillus sp. shown, to identify basic bacterial shapes and structures like endospores.

Darkfield: This technique modifies the condenser to block direct light, causing light to reflect off the specimen at an angle and producing a bright image against a dark background. It is exceptionally useful for increasing contrast in unstained, live specimens, such as the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi, which might be invisible in brightfield illumination.

Phase contrast: By exploiting the differences in the refractive index of various cellular components, this microscope creates high-contrast, high-resolution images without the need for staining. It is particularly valuable for observing live specimens and their internal organelles, as seen in the image of Pseudomonas sp., where internal density differences become visible.

Differential interference contrast (DIC): This method uses polarized light and interference patterns to enhance the contrast between different features of a specimen, resulting in a pseudo-three-dimensional appearance. It allows for the detailed visualization of internal structures within live, unstained organisms, such as the Escherichia coli O157:H7 bacterium.

Fluorescence: This microscope utilizes high-intensity UV or visible light to excite fluorescent molecules (fluorochromes) within a specimen, which then emit light at a lower energy to produce a bright image against a dark background. It is essential for identifying specific pathogens using immunofluorescence or visualizing specific cellular components, like the capsule of P. putida.

Confocal: Using a laser to scan multiple focal planes (z-planes) successively, this technique constructs a sharp, three-dimensional image by eliminating out-of-focus light. It is highly effective for examining thick specimens, such as the nucleoid regions of Escherichia coli cells embedded within complex biofilms.

Two-photon: This advanced scanning technique employs long-wavelength light, such as infrared, and fluorochromes to penetrate deeply into thick tissue samples with minimal phototoxicity. It is ideal for imaging deep structures in living tissues, as demonstrated by the detailed image of mouse intestine cells.

The Evolution and Utility of Light Microscopy

The microscope is the cornerstone of microbiology and histology, serving as the primary window into the cellular mechanisms of life. While the human eye can distinguish objects about 0.1 mm apart, light microscopes can resolve details as small as 0.2 micrometers, offering a magnification of up to 1000x. This capability is achieved through a series of lenses—the objective and the ocular—that refract light to enlarge the image of the specimen. However, magnification alone is not enough; the utility of a microscope is often defined by its resolution and its ability to generate contrast between the specimen and its background.

Different biological questions require different imaging modalities. For instance, while a standard pathology lab might rely on brightfield microscopy to view Gram-stained bacteria, a research facility studying cellular dynamics would require phase contrast or DIC to watch living cells divide without killing them with toxic stains. The choice of microscope depends heavily on the nature of the sample—whether it is alive or fixed, thick or thin, and whether specific molecules need to be tagged and tracked.

Key factors influencing the selection of a microscopy technique include:

- Specimen State: Whether the sample is a live culture or a fixed tissue slice.

- Contrast Needs: The natural opacity of the specimen versus the need for staining.

- Depth of Field: The requirement to see surface details versus internal 3D structures.

- Specificity: The need to identify specific proteins or DNA sequences using fluorescent markers.

Clinical Diagnosis: The Case of Lyme Disease

One of the most clinically significant examples of microscopy application involves the diagnosis of spirochetal infections. The Darkfield image provided highlights Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease. This bacterium is a spirochete, characterized by its long, helical, coil-shaped body. In a clinical setting, identifying these organisms in wet mounts of blood or tissue fluid can be challenging with standard brightfield microscopy because the bacteria are thin and do not contrast well with the bright background. Darkfield microscopy solves this by illuminating the sample from the side, causing the spirochetes to shine brightly against a black void, allowing for rapid visual confirmation of the pathogen’s presence and motility.

Lyme disease is a vector-borne illness transmitted to humans through the bite of infected black-legged ticks. If left untreated, the infection can spread to the joints, heart, and nervous system. Early symptoms often include fever, headache, fatigue, and a characteristic skin rash called erythema migrans. Because the bacteria can evade the immune system and disseminate into tissues, advanced visualization techniques are sometimes necessary for research and diagnosis, especially when serological blood tests are inconclusive. The ability to visualize the spirochete’s morphology helps researchers understand how it drills into tissue and evades host defenses.

Pathogenicity of E. coli O157:H7 and Biofilm Formation

The image also references Escherichia coli O157:H7 under Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) and Confocal microscopy. While most strains of E. coli are harmless commensals in the gut, the O157:H7 serotype is a potent pathogen that produces Shiga toxin. This toxin can cause severe damage to the lining of the intestine, leading to hemorrhagic colitis (bloody diarrhea) and, in severe cases, Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (HUS), which can result in kidney failure. DIC microscopy is particularly useful here because it reveals the surface topology and internal structure of the bacteria without staining, providing a “3D” relief view that helps scientists study the bacterium’s physical integrity and attachment mechanisms.

Furthermore, the mention of confocal and two-photon microscopy highlights the importance of studying biofilms. Biofilms are structured communities of bacteria that adhere to surfaces and produce a slimy protective matrix. Bacteria within biofilms, such as those formed by E. coli or Pseudomonas, are often highly resistant to antibiotics and immune attacks. Confocal microscopy allows researchers to optically section these thick biofilms, creating a 3D reconstruction of the bacterial community. This helps in understanding how nutrients flow through the colony and how the bacteria interact, which is crucial for developing treatments for chronic infections associated with medical implants and catheters.

Conclusion

From the rapid identification of spirochetes in a darkfield setup to the intricate 3D mapping of tissue with two-photon excitation, the spectrum of light microscopy techniques is vast and indispensable. Each method offers a unique perspective, allowing medical professionals to diagnose diseases like Lyme disease and analyze the virulence of pathogens like E. coli O157:H7 with greater accuracy. As optical technology continues to advance, our ability to probe the depths of biological tissues and microbial communities will only improve, leading to better diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies in medicine.