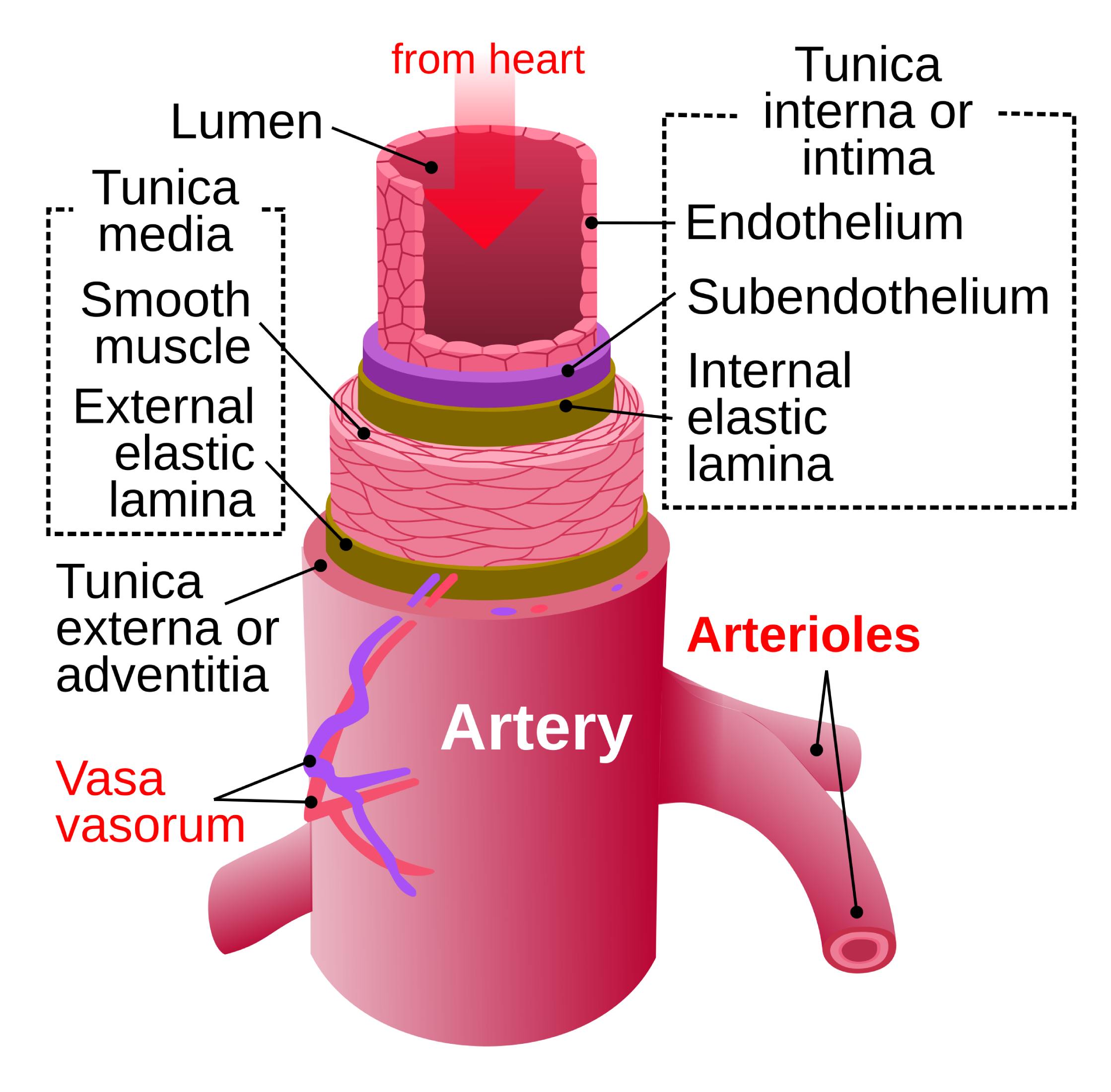

Arteries are complex, high-pressure blood vessels responsible for transporting oxygenated blood away from the heart to the body’s tissues. The structural integrity and functionality of an artery are maintained by its distinct layers—the tunica intima, tunica media, and tunica externa—each performing specialized roles in hemodynamics and vascular health. Understanding the microscopic anatomy of these vessels provides critical insight into how the cardiovascular system regulates blood pressure and ensures efficient nutrient delivery throughout the body.

Diagram Breakdown and Label Explanations

From heart:

This arrow indicates the direction of blood flow within the arterial system. In systemic circulation, blood is pumped forcefully from the left ventricle of the heart into the aorta and subsequent arteries to be distributed to peripheral tissues.

Lumen:

The lumen is the central hollow space within the vessel through which blood flows. The diameter of the lumen is actively regulated by the smooth muscle in the vessel wall, which directly influences vascular resistance and blood pressure.

Tunica interna or intima:

This is the innermost layer of the arterial wall, designed to minimize friction as blood travels through the vessel. It consists of the endothelial lining and underlying connective tissue, playing a crucial role in preventing blood clot formation.

Endothelium:

The endothelium is a single layer of squamous epithelial cells that lines the interior surface of the blood vessel. Beyond acting as a physical barrier, these cells are metabolically active, releasing substances like nitric oxide to regulate vascular tone and immune response.

Subendothelium:

Located immediately beneath the endothelial cells, the subendothelium is a thin layer of loose connective tissue. It provides structural support to the endothelium and acts as a cushion to absorb some of the mechanical stress exerted by blood flow.

Internal elastic lamina:

This is a fenestrated layer of elastic tissue that separates the tunica intima from the tunica media. Its Swiss-cheese-like structure allows substances to diffuse to deeper layers while providing the elasticity needed for the vessel to expand and recoil during the cardiac cycle.

Tunica media:

The tunica media is the middle and typically the thickest layer of an artery, composed primarily of smooth muscle cells and elastic fibers. This layer is responsible for vasoconstriction and vasodilation, allowing the body to control blood distribution and pressure.

Smooth muscle:

Arranged circularly within the tunica media, smooth muscle cells contract or relax in response to neural and chemical signals. This muscular activity changes the vessel diameter, thereby regulating systemic vascular resistance and blood flow to specific organs.

External elastic lamina:

This distinct sheet of elastic fibers serves as the boundary between the tunica media and the outer tunica externa. It provides additional structural flexibility, allowing the artery to withstand the high pulsatile pressure generated by the heart.

Tunica externa or adventitia:

The outermost layer of the blood vessel, the tunica externa, is composed primarily of collagen fibers that reinforce the wall and anchor the artery to surrounding tissues. It prevents the vessel from over-expanding and potentially rupturing under high pressure.

Artery:

The artery is the primary vessel type depicted, characterized by thick, muscular walls capable of handling high pressure. Unlike veins, arteries maintain their circular shape even when empty due to the rigidity of their tunica media.

Arterioles:

These are smaller branches extending from the main artery that lead into the capillary beds. Arterioles are known as resistance vessels because they are the primary site where blood pressure drops and flow is regulated before entering the delicate capillaries.

Vasa vasorum:

Translated as “vessels of the vessels,” these are networks of tiny blood vessels found in the tunica externa and outer tunica media of large arteries. Since the walls of large arteries are too thick for nutrients to diffuse from the lumen to the outer layers, the vasa vasorum provide this essential blood supply.

The Physiology and Mechanics of Arterial Walls

The arterial system is not merely a network of passive tubes; it is a dynamic organ system capable of significant physiological adaptation. The structure of an artery is intimately linked to its function as a conduit for high-pressure transport. The heart generates significant force during systole, and the arterial walls must be robust enough to withstand this pressure without bursting, yet elastic enough to recoil during diastole. This recoil mechanism, primarily facilitated by the elastic laminae within the vessel walls, helps maintain a continuous flow of blood even when the heart is relaxing between beats, a phenomenon known as the Windkessel effect.

The histological composition of the arterial wall changes as the vessels move further from the heart. Large vessels near the heart, such as the aorta, are classified as elastic arteries because they contain a higher proportion of elastin to handle massive pressure fluctuations. As the vessels branch into smaller arteries and arterioles, the composition shifts to become more muscular. This increase in smooth muscle relative to elastic tissue allows these distal vessels to exert finer control over blood flow distribution, directing blood to active muscles during exercise or diverting it to the digestive tract after a meal.

Furthermore, the health of the arterial wall is paramount to cardiovascular longevity. The endothelium acts as a gatekeeper; when healthy, it prevents the adhesion of platelets and white blood cells. However, damage to this delicate lining—often caused by hypertension, smoking, or high cholesterol—can initiate the process of atherosclerosis. This condition involves the buildup of plaque within the tunica intima, narrowing the lumen and stiffening the vessel wall.

Key functions of the arterial structure include:

- Pressure Dampening: Converting the pulsatile flow from the heart into a smoother flow for capillaries.

- Blood Distribution: Selectively constricting or dilating to prioritize blood flow to vital organs.

- Structural Support: Withstanding high internal hydrostatic pressure through collagen reinforcement.

- Metabolic Regulation: The endothelium synthesizes vasoactive substances that control clotting and inflammation.

Conclusion

The detailed anatomy of an artery, from the protective tunica externa to the microscopic endothelium, illustrates the incredible engineering of the human cardiovascular system. Each layer—whether it is the contractile tunica media or the nutritive vasa vasorum—serves a specific purpose in maintaining hemostasis and ensuring that oxygen-rich blood reaches every cell in the body. A thorough understanding of these structures is essential for medical professionals when diagnosing and treating vascular pathologies such as aneurysms, atherosclerosis, and hypertension.