The anatomy of the human neck is a dense and complex intersection of the respiratory, digestive, and neurovascular systems. This cadaveric dissection highlights the critical relationship between the common carotid artery, the deep cervical muscles, and the major nerve networks that facilitate life-sustaining functions. Understanding these spatial arrangements is vital for medical professionals, particularly those specializing in vascular surgery, anesthesiology, and emergency medicine, where navigating the neck’s delicate landscape requires extreme precision.

SUBMANDIBULAR GLAND: This major salivary gland is located within the submandibular triangle, just beneath the body of the mandible. It is responsible for producing the majority of the mouth’s unstimulated saliva, which aids in digestion and oral hygiene.

THYROID CARTILAGE: Often referred to as the “Adam’s apple,” this is the largest of the nine cartilages that compose the laryngeal skeleton. It serves to protect the vocal cords and provides an attachment point for various muscles that assist in swallowing and vocalization.

STERNOHYOID MUSCLE: A thin, narrow muscle belonging to the infrahyoid “strap” group that connects the sternum to the hyoid bone. Its primary physiological function is to depress the hyoid bone during the final stages of the swallowing process.

OMOHYOID MUSCLE- superior belly: This upper segment of the omohyoid muscle originates from an intermediate tendon and attaches to the lower border of the hyoid bone. Working in tandem with its inferior counterpart, it assists in depressing the hyoid and tensing the deep cervical fascia to prevent venous collapse during inspiration.

STERNOCLEIDOMASTOID MUSCLE: This robust, superficial muscle is one of the most prominent landmarks of the neck, running from the sternum and clavicle to the mastoid process. It is responsible for rotating the head to the opposite side and flexing the neck when acting bilaterally.

ANTERIOR SCALENE MUSCLE: This muscle arises from the transverse processes of the C3–C6 vertebrae and inserts into the first rib. It is an essential clinical landmark as it separates the subclavian vein from the subclavian artery and the brachial plexus.

SUBCLAVIUS MUSCLE: A small, triangular muscle situated in the narrow gap between the first rib and the clavicle. It functions to stabilize the clavicle during movements of the shoulder girdle and provides a layer of protection to the underlying neurovascular bundle.

CLAVICLE: Commonly known as the collarbone, this S-shaped bone acts as a structural strut between the scapula and the sternum. It is the only long bone in the body that lies horizontally and is frequently used as a landmark for regional anesthesia and central line placement.

MIDDLE SCALENE MUSCLE: This is the largest and longest of the scalene muscles, originating from the C2–C7 vertebrae and inserting onto the first rib. It serves as an accessory muscle of respiration by elevating the first rib and also aids in lateral flexion of the neck.

BRACHIAL PLEXUS: This complex network of nerves is formed by the anterior rami of the C5–T1 spinal nerves and provides motor and sensory innervation to the upper limb. It emerges through the interscalene space, located between the anterior and middle scalene muscles.

OMOHYOID MUSCLE- inferior belly: This portion arises from the superior border of the scapula and travels obliquely across the posterior triangle of the neck. It joins the superior belly via an intermediate tendon, which is often tethered to the internal jugular vein.

POSTERIOR SCALENE MUSCLE: The smallest and deepest of the scalene muscles, it originates from the transverse processes of the lower cervical vertebrae and inserts into the second rib. Its contraction assists in elevating the second rib during forced inspiration and contributes to neck stability.

VAGUS NERVE: Also known as cranial nerve X, the vagus nerve is the longest cranial nerve and carries extensive parasympathetic fibers to the thoracic and abdominal viscera. In the neck, it descends within the carotid sheath, positioned posteriorly between the common carotid artery and the internal jugular vein.

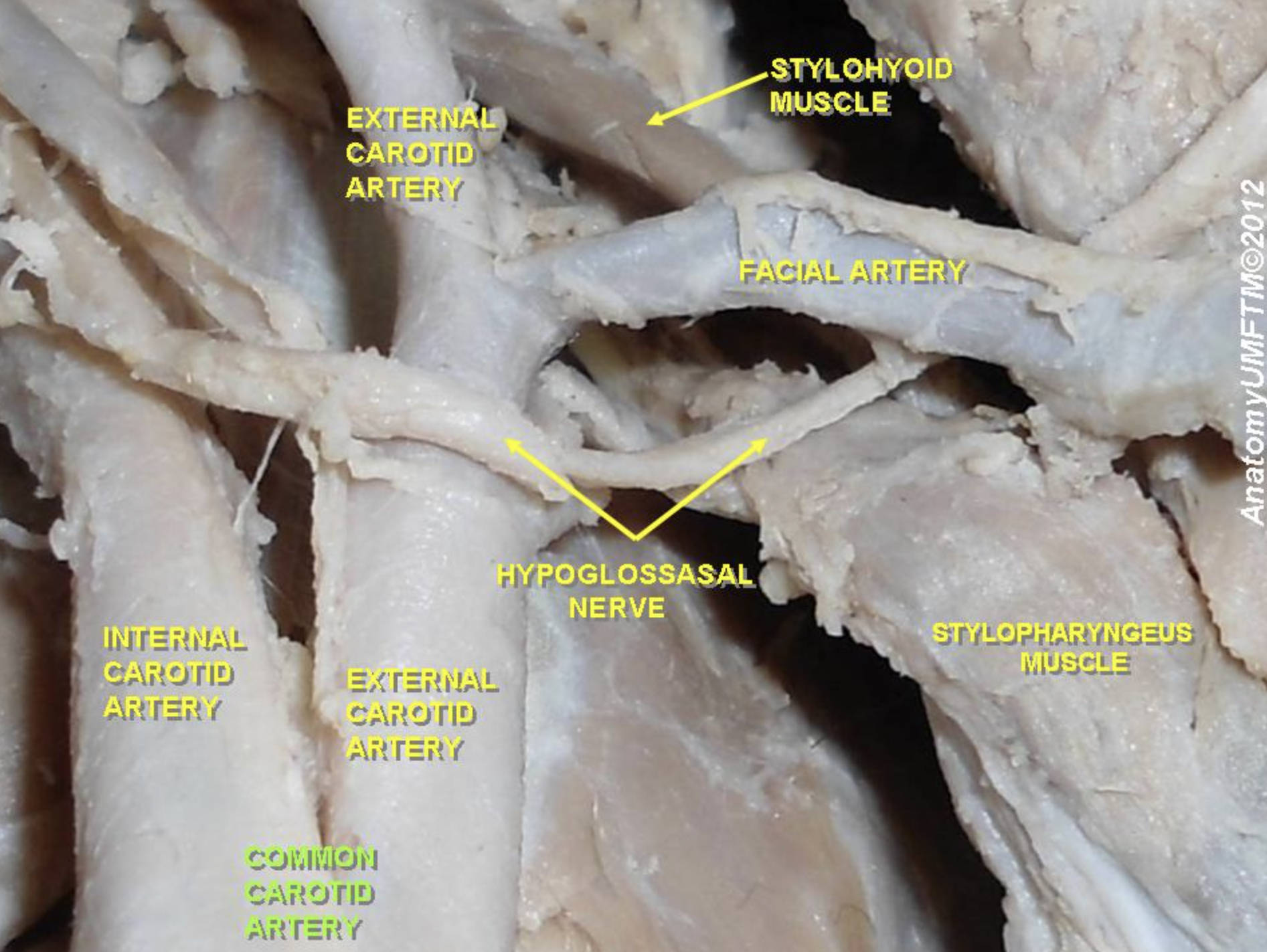

COMMON CAROTID ARTERY: This major vessel provides the primary oxygenated blood supply to the head and neck regions. It ascends through the neck and typically bifurcates into the internal and external carotid arteries at the level of the upper border of the thyroid cartilage.

The Structural Organization of the Neck

The human neck is partitioned into compartments by several layers of deep cervical fascia. The most critical compartment shown here is the carotid sheath, a tubular investment of fascia that encloses the common carotid artery, the internal jugular vein, and the vagus nerve. This anatomical packaging ensures that these vital neurovascular structures are protected from external trauma and infection while allowing for the necessary flexibility of the cervical spine.

Beyond the vascular channels, the muscular architecture of the neck provides both mechanical support and a guide for clinicians. The scalene muscles, for example, are not only involved in neck movement and respiration but also define the interscalene space. This space is of paramount importance in regional anesthesia, as it is the site where the brachial plexus can be safely accessed for nerve blocks during shoulder or upper arm surgeries.

Key functional groupings in the neck include:

- The infrahyoid (strap) muscles, which control the position of the larynx and hyoid bone.

- The scalene muscles, which act as accessory muscles of inspiration and lateral flexors.

- The salivary glands, which facilitate the initial chemical breakdown of food.

- The primary neurovascular bundle, responsible for cerebral perfusion and autonomic regulation.

Clinical Relevance and Disease Pathology

The common carotid artery is a site of significant clinical interest, particularly regarding carotid artery disease. This condition occurs when atherosclerotic plaque builds up within the arterial walls, narrowing the lumen and restricting blood flow to the brain. If a piece of this plaque breaks loose (an embolus) or if a blood pool forms a clot on the plaque’s surface, it can travel to the brain and cause an ischemic stroke, a leading cause of long-term disability and death.

Understanding the relationship between the carotid artery and the cervical plexus is also essential for diagnostic purposes. When a patient presents with a carotid bruit—a “whooshing” sound heard via stethoscope—clinicians must differentiate between vascular stenosis and other soft tissue abnormalities. Furthermore, the vagus nerve’s role in cardiac regulation means that pressure applied to the carotid sinus (located at the bifurcation) can result in a vasovagal response, potentially lowering the heart rate and blood pressure significantly.

Finally, the region encompassing the first rib and the clavicle is known as the thoracic outlet. Structural abnormalities in this area, such as a cervical rib or muscular hypertrophy of the anterior scalene, can lead to Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS). This condition results in the compression of the nerves or blood vessels, causing pain, numbness, and weakness in the arm and hand, highlighting how interconnected the neck anatomy is with the functionality of the upper extremities.

In summary, the detailed anatomical landmarks visible in this cadaveric specimen provide the foundation for surgical precision and medical diagnosis. From the salivary functions of the submandibular gland to the complex motor signals of the brachial plexus, every structure plays a specialized role. Mastery of this anatomy ensures that medical interventions in the neck remain safe, effective, and minimally invasive.