Comparing Transmission Electron Microscopy and Light Microscopy: Principles and Medical Applications

Medical diagnostics and biological research rely heavily on advanced imaging technologies to visualize cellular structures that are invisible to the naked eye. This detailed comparison explores the fundamental operational differences between Transmission Electron Microscopes (TEM) and standard Light Microscopes, illustrating how electron beams manipulated by magnetic fields offer superior resolution compared to visible light focused by glass lenses for analyzing the intricate ultrastructure of biological tissues.

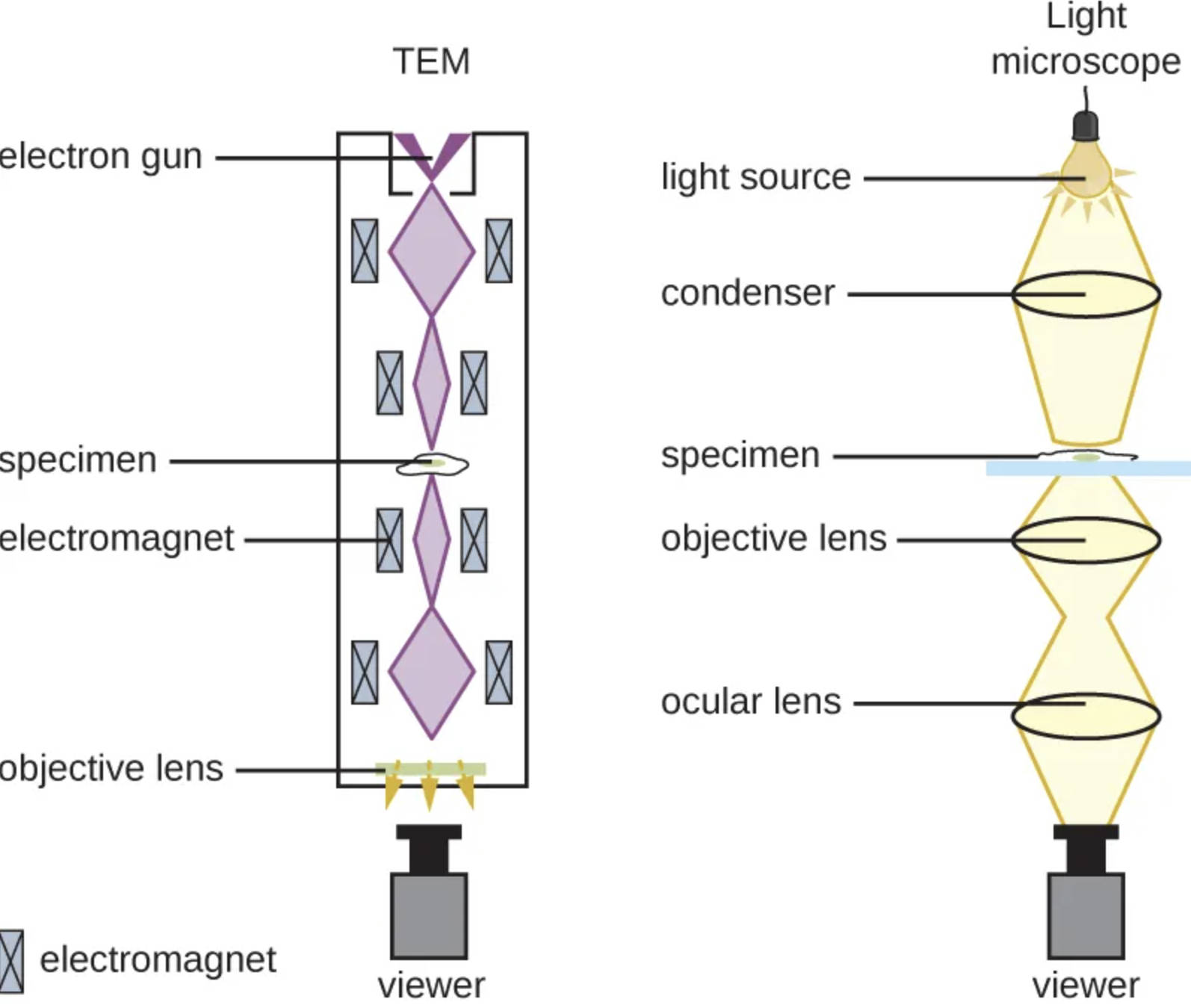

TEM: This acronym stands for Transmission Electron Microscope, which is the high-tech instrument depicted on the left side of the diagram. It utilizes a particle beam of electrons to visualize specimens and is capable of significantly higher magnification than optical instruments, often revealing details at the nanometer scale.

Electron gun: Located at the top of the TEM column, this component is responsible for generating the source of illumination. It emits a high-voltage stream of electrons that travels downward through the vacuum column to interact with the biological sample.

Specimen: In the context of the TEM, the specimen is an incredibly thin slice of biological tissue, typically less than 100 nanometers thick, placed in the path of the electron beam. For the light microscope, the specimen is placed on a glass slide and can be slightly thicker, though it still must be translucent enough to allow light to pass through.

Electromagnet: These components serve as the “lenses” within the electron microscope, replacing the glass lenses found in optical systems. Because electrons have a negative charge, these circular magnetic coils generate fields that focus and bend the electron beam, directing it precisely through the column and the specimen.

Objective lens: In the TEM diagram, this is an electromagnetic lens located below the specimen that creates the initial magnified image. In the light microscope, the objective lens is a glass optical element positioned just above the sample, responsible for gathering light and providing the primary magnification power.

Viewer: This represents the final detection point where the magnified image is observed by the scientist or pathologist. In a TEM, this is typically a fluorescent screen or a digital sensor that converts electron patterns into a visual image, whereas in a light microscope, it is often a camera or the human eye looking through an eyepiece.

Light microscope: Depicted on the right side of the diagram, this is the standard optical instrument used in most clinical laboratories and classrooms. It relies on the visible spectrum of light and glass lenses to magnify cells and tissues up to approximately 1000 times their original size.

Light source: Located at the top of the diagram (though often at the base in modern units), this bulb provides the photons necessary to illuminate the sample. The light emitted travels through the condenser and the specimen to form the visible image.

Condenser: This lens system is situated between the light source and the specimen in the light microscope. Its primary function is to gather and concentrate the light rays into a tight cone, ensuring the sample is evenly and brightly illuminated for optimal viewing.

Ocular lens: Also known as the eyepiece, this is the glass lens closest to the observer’s eye in the light microscope assembly. It further magnifies the image produced by the objective lens, allowing the viewer to see the details of the specimen comfortably.

The Evolution of Microscopic Imaging

The quest to understand the building blocks of life has driven the evolution of microscopy from simple glass magnifying tools to complex particle accelerators. The light microscope, a staple in science since the 17th century, uses visible light to illuminate samples. While effective for observing general cell shapes, bacteria, and tissue architecture, its resolving power is physically limited by the wavelength of visible light. This boundary, known as the diffraction limit, prevents the clear distinction of two points closer than approximately 200 nanometers.

To bypass this physical limitation and visualize smaller structures, scientists developed the Transmission Electron Microscope. Instead of photons, the TEM uses electrons, which have a wavelength roughly 100,000 times shorter than visible light. This drastically shorter wavelength allows for a massive increase in resolution, enabling the visualization of structures as small as individual protein complexes or viral particles. The diagram above beautifully illustrates the parallel architecture of these two systems, showing how the principles of physics remain consistent even when the medium changes from light to electrons.

The transition from optical to electron microscopy involves replacing glass with magnetic fields. In a light microscope, curved glass refraps (bends) light rays to focus them. Electrons, however, cannot travel through glass and are easily scattered by air molecules. Therefore, the TEM operates in a high-vacuum environment and uses variable magnetic fields to steer the negatively charged electrons. This allows for precise control over magnification and focus, far exceeding the capabilities of glass optics.

Key differences between these two imaging systems include:

- Illumination Source: Light microscopes use photons (light bulbs), while TEMs use electrons (electron guns).

- Focusing Mechanism: Light microscopes use curved glass lenses; TEMs use toroidal electromagnets.

- Environment: Light microscopy occurs in ambient air, whereas TEM requires a high vacuum to prevent electron scattering.

- Image Formation: Light images are viewed directly by the eye; TEM images are projected onto a fluorescent screen or digital detector.

Anatomical and Physiological Visualization

The superior resolving power of the TEM is essential for defining the ultrastructure of human anatomy. While a light microscope can show a pathologist the general arrangement of liver cells (hepatocytes) and their nuclei, an electron microscope is required to see the internal organelles that drive physiological function. For instance, the TEM can reveal the cristae within mitochondria, the folded inner membranes where cellular respiration and ATP production occur. This level of detail is critical for diagnosing mitochondrial myopathies, where the internal structure of these organelles is disrupted.

Furthermore, the mechanisms of cellular transport are best understood through electron microscopy. The diagram highlights how electromagnetic lenses focus the beam to a sharp point, allowing researchers to capture images of synaptic vesicles in nerve cells. These tiny sacs contain neurotransmitters essential for brain communication. Physiological processes, such as the fusion of these vesicles with the cell membrane during exocytosis, happen at a scale invisible to light microscopy. By using magnetic focusing, scientists can observe the density and organization of these vesicles, providing insights into neurodegenerative conditions.

The comparison of the “objective lens” in both systems highlights a crucial functional parallel. In both instruments, this lens is the most critical determinant of image quality. In the light microscope, the numerical aperture of the glass objective determines how much light is gathered. In the TEM, the stability and precision of the magnetic field in the objective lens determine the resolution. Any fluctuation in the current supplying the electromagnetic lenses can cause image distortion, known as astigmatism. This makes the engineering of the TEM column a feat of high-precision physics, enabling the diagnosis of diseases like ciliary dyskinesia by visualizing the dynein arms on the microtubules of cilia.

Conclusion

The side-by-side comparison of the Transmission Electron Microscope and the Light Microscope illustrates how different physical principles can achieve the same goal: magnification. While the light microscope remains the workhorse for general screening and tissue analysis, the electron microscope is the ultimate tool for structural precision. By harnessing the properties of electrons and manipulating them with magnets, medical science can peer into the very machinery of life, bridging the gap between gross anatomy and molecular biology.

Keywords: