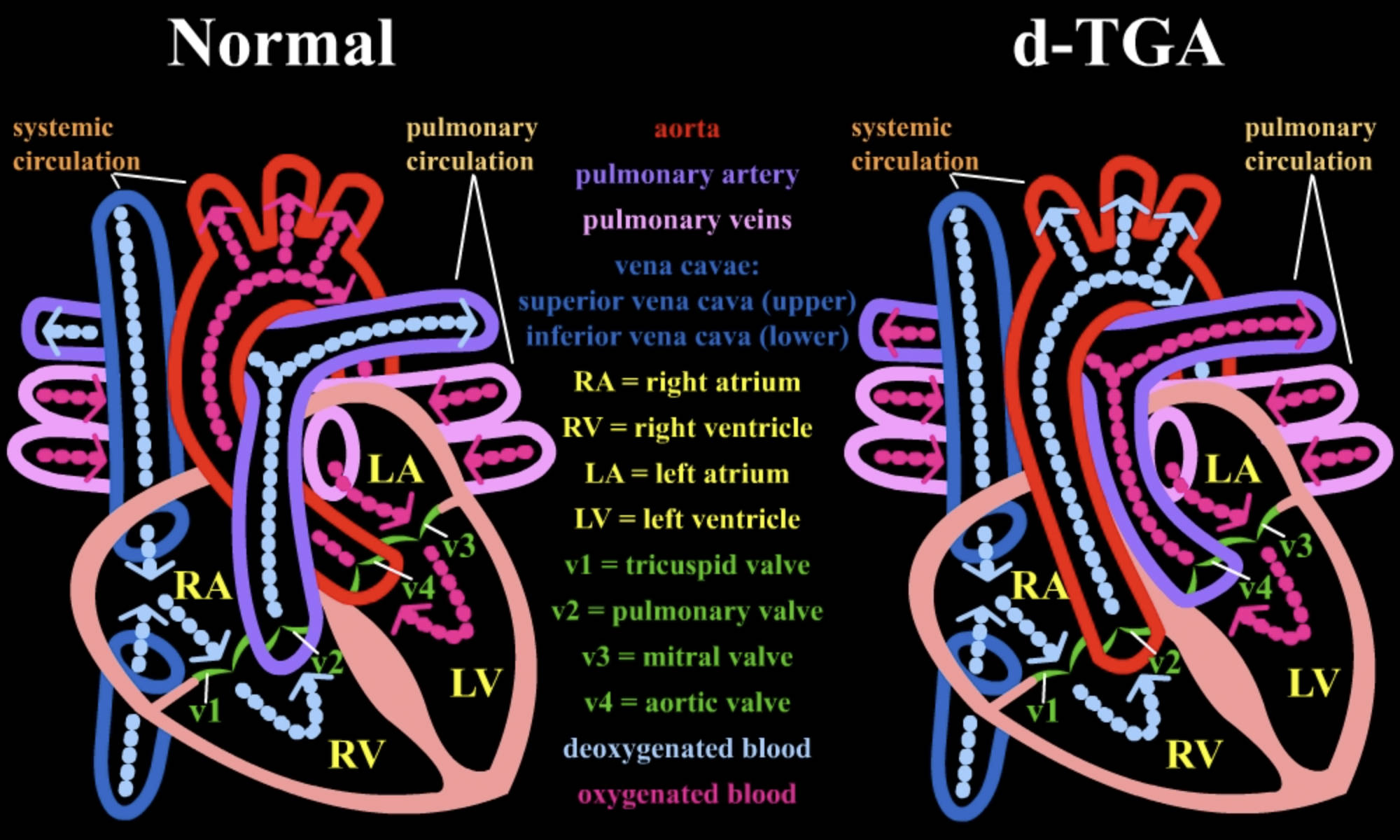

This comprehensive comparison illustrates the fundamental differences between the anatomy of a healthy human heart and one affected by Dextro-Transposition of the Great Arteries (d-TGA), a critical congenital defect. By distinguishing between the standard “series” circulation, where blood flows in a figure-eight pattern, and the pathological “parallel” circulation of d-TGA, we can better understand the severe physiological implications of this condition. The diagram highlights how the reversal of the great vessels prevents oxygenated blood from reaching the systemic body tissues, creating a medical emergency in newborns.

Systemic circulation: This vascular network delivers blood to the body’s tissues and returns it to the heart. In the normal heart, this path carries oxygen-rich blood, whereas in d-TGA, it futilely recirculates oxygen-poor blood.

Pulmonary circulation: This loop is responsible for transporting blood to the lungs for gas exchange. In a normal heart, it receives deoxygenated blood, but in d-TGA, it receives already oxygenated blood, creating an inefficient cycle.

Aorta: The aorta is the body’s main artery, normally arising from the left ventricle to distribute oxygenated blood. In d-TGA, it incorrectly originates from the right ventricle, pumping deoxygenated blood back to the body.

Pulmonary artery: This vessel normally carries oxygen-poor blood from the right ventricle to the lungs. In the d-TGA heart, it arises from the left ventricle, returning oxygen-rich blood to the lungs unnecessarily.

Pulmonary veins: These four veins carry oxygenated blood from the lungs back to the left atrium. This connection remains normal in d-TGA, but the blood is subsequently misdirected due to the ventricular outflow abnormality.

Vena cavae: Consisting of the superior and inferior vena cava, these large veins return deoxygenated blood from the body to the right atrium. Their connection is anatomically correct in both normal and d-TGA hearts.

Superior vena cava (upper): This vein collects deoxygenated blood from the head, neck, and arms. It empties into the right atrium, initiating the cycle of blood return to the heart.

Inferior vena cava (lower): This vein transports deoxygenated blood from the lower limbs and abdomen. Like the superior vena cava, it drains into the right atrium.

RA = right atrium: The upper right chamber of the heart that receives deoxygenated blood from the body. In both heart types, it pumps blood down into the right ventricle.

RV = right ventricle: The lower right chamber responsible for pumping blood. In a normal heart, it sends blood to the lungs; in d-TGA, it is forced to pump deoxygenated blood into the aorta and out to the body.

LA = left atrium: The upper left chamber that receives oxygenated blood from the pulmonary veins. It passes this red, oxygen-rich blood down into the left ventricle.

LV = left ventricle: The heart’s main pumping chamber, which is thick and muscular. In a normal heart, it supplies the body, but in d-TGA, it pumps oxygenated blood back into the pulmonary artery and lungs.

v1 = tricuspid valve: Located between the right atrium and right ventricle, this valve prevents backflow into the atrium. It operates normally in d-TGA, passing deoxygenated blood into the RV.

v2 = pulmonary valve: In a normal heart, this valve controls blood flow from the RV to the pulmonary artery. In d-TGA, the valve in this position (exiting the RV) functions as the aortic valve because the aorta is attached there.

v3 = mitral valve: This valve sits between the left atrium and left ventricle. It facilitates the flow of oxygenated blood into the ventricle during diastole.

v4 = aortic valve: Normally located between the LV and the aorta. In d-TGA, the valve in this position (exiting the LV) leads to the pulmonary artery, effectively acting as a pulmonary valve.

Deoxygenated blood: Represented in blue, this blood has depleted its oxygen supply and is rich in carbon dioxide. In d-TGA, this blood is trapped in a loop that constantly bypasses the lungs.

Oxygenated blood: Represented in pink/red, this blood has been replenished with oxygen in the lungs. In d-TGA, this blood is trapped in the pulmonary loop and fails to reach the rest of the body.

The Physiology of Normal vs. Transposed Circulation

The human heart is designed to operate as a pump in series, meaning the blood follows a single continuous path: from the body to the heart, to the lungs, back to the heart, and finally back to the body. As seen on the left side of the diagram, this ensures that every drop of blood pumped to the brain and vital organs carries oxygen. The right side of the heart is dedicated to low-pressure pumping to the lungs, while the left side handles high-pressure pumping to the systemic circulation. This efficient separation prevents the mixing of blue (deoxygenated) and red (oxygenated) blood.

However, in the case of Dextro-Transposition of the Great Arteries, illustrated on the right, this architecture is fundamentally disrupted. The aorta and the pulmonary artery have swapped positions. This creates two parallel, independent circulatory loops. In one loop, oxygen-poor blood circulates from the body to the right heart and back to the body without ever seeing the lungs. In the second loop, oxygen-rich blood shuttles from the lungs to the left heart and back to the lungs without ever reaching the body.

This anatomy is incompatible with life unless there are connections allowing the blood to mix. In a developing fetus, this is not an issue because the lungs are not yet used for oxygenation. However, immediately upon birth, the separation of these systems becomes critical. The infant survives only if natural fetal shunts, such as the ductus arteriosus or the foramen ovale, remain open to allow some oxygenated blood to cross over into the systemic circulation.

Key differences highlighted in the diagram include:

- Vessel Origin: The aorta exits the right ventricle in d-TGA, whereas it exits the left ventricle normally.

- Blood Destination: The right ventricle pumps to the body in d-TGA, rather than to the lungs.

- Oxygen Delivery: Systemic tissues receive blue blood in d-TGA, leading to immediate cyanosis.

- Ventricular Workload: The right ventricle is forced to pump against high systemic pressure in d-TGA, which can lead to hypertrophy and failure if uncorrected.

Clinical Implications of d-TGA

Dextro-Transposition of the Great Arteries is a congenital heart defect that constitutes a medical emergency. The primary clinical sign is cyanosis, a bluish discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes, which is often visible within the first few hours of life. Because the oxygenated blood is effectively “locked” in the pulmonary loop, administering supplemental oxygen to the newborn often yields little to no improvement in oxygen saturation levels. This lack of response to oxygen therapy is a classic diagnostic clue that prompts immediate echocardiography to confirm the transposition of the vessels.

Without medical intervention, the tissues of the body will suffer from severe hypoxia (lack of oxygen) and acidosis. To keep the newborn alive prior to surgery, neonatologists often administer a medication called prostaglandin E1. This drug prevents the closure of the ductus arteriosus, a small vessel connecting the aorta and pulmonary artery. Keeping this channel open allows for the mixing of blood between the two parallel circuits, buying vital time for the patient. In some cases, a procedure called a balloon atrial septostomy is performed to widen the hole between the upper chambers of the heart, further enhancing blood mixing.

The definitive treatment for d-TGA is the arterial switch operation (ASO). Performed typically within the first weeks of life, this open-heart surgery involves physically detaching the aorta and pulmonary artery and reattaching them to their correct ventricles. Crucially, the tiny coronary arteries that supply the heart muscle must also be moved to the new aorta. This procedure restores the normal “series” circulation shown on the left side of the diagram. With successful surgery, the long-term prognosis for these children is generally excellent, allowing for normal growth and development.

Conclusion

The visual comparison between a normal heart and a d-TGA heart underscores the intricate precision required for human circulation. While the internal chambers—the atria and ventricles—may look similar in both diagrams, the incorrect placement of the outflow vessels drastically alters the physics of blood flow. Understanding this parallel circulation model is essential for parents and medical professionals to grasp why rapid surgical correction is necessary to transform a fatal anatomy into a functional, life-sustaining system.