Cellular replication is the fundamental biological mechanism that drives life, enabling organisms to grow, repair damaged tissues, and pass genetic information to the next generation. By understanding the distinct pathways of meiosis and mitosis, we can gain insight into how the human body maintains genetic consistency in skin or liver tissue while fostering necessary variation in reproductive lineages. This comparison highlights the intricate checkpoints and chromosomal movements that ensure every cell performs its specialized physiological role.

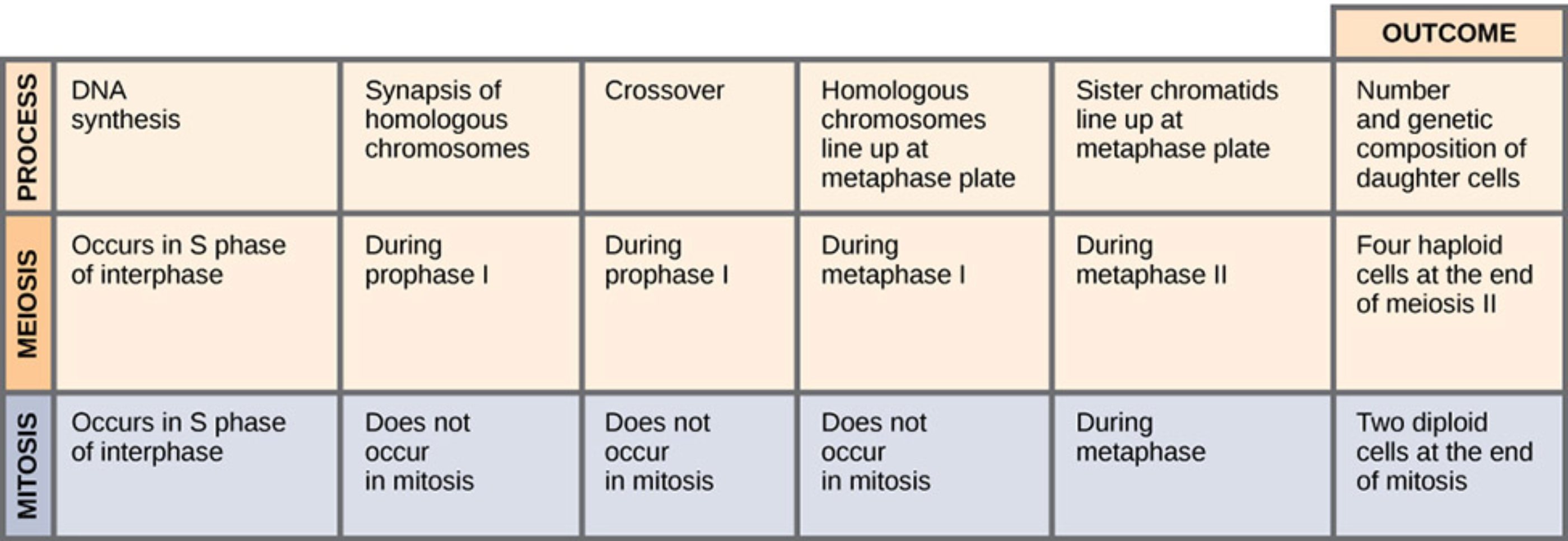

Process: This header refers to the various biochemical and mechanical stages that occur during cellular replication. It categorizes the specific events that distinguish the different paths of division, such as genetic recombination and chromosomal alignment.

Meiosis: This is a specialized form of nuclear division that reduces the chromosome number by half, typically occurring in the germline. It is essential for sexual reproduction and leads to the production of four genetically unique haploid cells.

Mitosis: This is the standard method of cell division in eukaryotes that results in two daughter cells with the same number of chromosomes as the parent nucleus. It is the primary process used for tissue growth, development, and routine physiological repair throughout an organism’s life.

Outcome: This section identifies the final biological results of the division process at a cellular level. It specifies the total number of daughter cells produced and their overall genetic relationship to the original parent cell.

DNA synthesis: This is the physiological process of creating a new strand of DNA from a template strand. In both mitosis and meiosis, this occurs during the S phase of interphase to ensure that genetic material is doubled before the actual division begins.

Synapsis of homologous chromosomes: This is the pairing of two homologous chromosomes that occurs specifically during the early stages of meiosis. This physical association is a prerequisite for chromosomal crossover and does not take place during standard mitotic division.

Crossover: Also known as genetic recombination, this event involves the exchange of segments of genetic material between non-sister chromatids of homologous chromosomes. This process is a hallmark of Prophase I in meiosis and is the primary driver of genetic variation in offspring.

Homologous chromosomes line up at metaphase plate: This specific alignment occurs during Metaphase I of meiosis, where pairs of chromosomes sit side-by-side at the cell’s center. In mitosis, this paired alignment is absent because chromosomes align individually to ensure identical distribution.

Sister chromatids line up at metaphase plate: This describes the alignment of individual chromosomes, each consisting of two identical chromatids, along the equatorial plane of the cell. This specific positioning occurs during Metaphase in mitosis and during Metaphase II in the second stage of meiosis.

Number and genetic composition of daughter cells: This is the qualitative and quantitative result measured at the conclusion of the entire cell cycle. It highlights whether the resulting cells are diploid clones suited for tissue structure or unique haploid units prepared for fertilization.

Occurs in S phase of interphase: This refers to the specific timing in the cell cycle when the genome is replicated. This step is a critical prerequisite for both types of division to ensure that each daughter cell receives a complete set of genetic instructions.

During prophase I: This is the first stage of the first meiotic division where synapsis and crossing over take place. These events are vital for shuffling the genetic deck, ensuring that no two gametes are exactly alike.

During metaphase I: This is the stage in meiosis where homologous pairs are positioned at the metaphase plate. The random orientation of these pairs leads to independent assortment, further diversifying the genetic outcome.

During metaphase II: This stage occurs in the second meiotic division where single chromosomes line up at the center of the cell. It ensures that the sister chromatids will be pulled apart into separate daughter cells, completing the reduction to a haploid state.

Four haploid cells at the end of meiosis II: This is the final biological product of a complete meiotic cycle. These cells contain only half the original number of chromosomes (n) and are genetically distinct from the parent and each other.

Does not occur in mitosis: This phrase clarifies that certain complex meiotic processes, like synapsis and crossing over, are entirely absent in standard cell replication. Mitosis is evolutionarily designed to maintain genetic continuity and stability rather than promote diversity.

During metaphase: This is the phase in mitosis where chromosomes align individually at the cell’s equator. This precise positioning ensures that each of the two resulting daughter cells inherits an identical and complete set of genetic information.

Two diploid cells at the end of mitosis: These are the daughter cells resulting from a single round of mitotic division. They are genetically identical clones of the parent cell and contain two complete sets of chromosomes (2n).

The Fundamental Roles of Cellular Division

At its core, cell division is the process by which a parent cell divides into two or more daughter cells. In human physiology, this is divided into two major categories: mitosis and meiosis. Mitosis is responsible for the proliferation of somatic cells, which include everything from the neurons in your brain to the myocytes in your heart. Without mitosis, the body would be unable to heal a simple paper cut or grow from an embryo into an adult.

Meiosis, however, is a much more specialized process restricted to the gonads—the testes in males and the ovaries in females. Its primary function is the production of gametes, such as sperm and egg cells. Unlike mitosis, which preserves the number of chromosomes, meiosis reduces the count by half. This reduction is vital because when fertilization occurs, the fusion of two haploid cells restores the diploid number in the zygote, preventing an unsustainable doubling of DNA with every generation.

The distinction between these two processes is governed by several key factors:

- The frequency of DNA replication relative to nuclear division.

- the presence or absence of homologous chromosome pairing.

- The degree of genetic variation produced in the daughter cells.

- The specific anatomical locations where the division occurs.

Physiological Mechanisms of Genetic Maintenance

The journey of any dividing cell begins in interphase, specifically the S phase, where DNA polymerase enzymes facilitate the replication of the entire genome. Following this, the cell enters its respective division pathway. In mitosis, the goal is genomic stability. The chromosomes condense and align individually at the metaphase plate. Spindle fibers then pull the sister chromatids to opposite poles, ensuring that each new nucleus contains an exact copy of the parent DNA. This precision is why your liver cells remain liver cells and your skin cells maintain their protective properties after every division.

In contrast, meiosis introduces complexity through two successive rounds of division. During Prophase I, homologous recombination occurs through crossover events. This is a highly regulated physiological process where physical breaks in the DNA are repaired by swapping segments between maternal and paternal chromosomes. This shuffling is why children inherit a mix of traits from their grandparents, creating a unique genetic “fingerprint” for every individual. This variation is the cornerstone of biological resilience, allowing populations to adapt to environmental stressors and diseases.

Anatomical Context and Biological Outcomes

The anatomical context of these divisions is strictly defined by the body’s needs. Mitosis occurs continuously in high-turnover tissues; for example, the basal layer of the skin and the lining of the gastrointestinal tract are in a constant state of mitotic flux. On the physiological level, this requires a massive amount of energy and nutrient resources to synthesize new organelles and plasma membranes. If this process is disrupted, it can lead to issues ranging from delayed wound healing to the uncontrolled proliferation seen in oncological conditions.

Meiosis is a more punctuated and regulated process. In males, spermatogenesis occurs continuously from puberty onwards within the seminiferous tubules. In females, oogenesis begins before birth, pauses, and then resumes on a monthly cycle starting at puberty. The final outcome—four unique haploid cells in males or one functional ovum and polar bodies in females—is the culmination of the complex chromosomal “dance” described in the meiotic stages. This specialized division ensures the continuity of the human species while providing the genetic diversity necessary for evolution.

Ultimately, mitosis and meiosis are two sides of the same biological coin. One maintains the “now” by preserving the structural and functional integrity of the individual’s body, while the other prepares for the “future” by carefully crafting the genetic makeup of the next generation. Understanding these processes is essential for medical professionals and students alike, as it forms the basis of our knowledge regarding growth, heredity, and the cellular foundations of health.