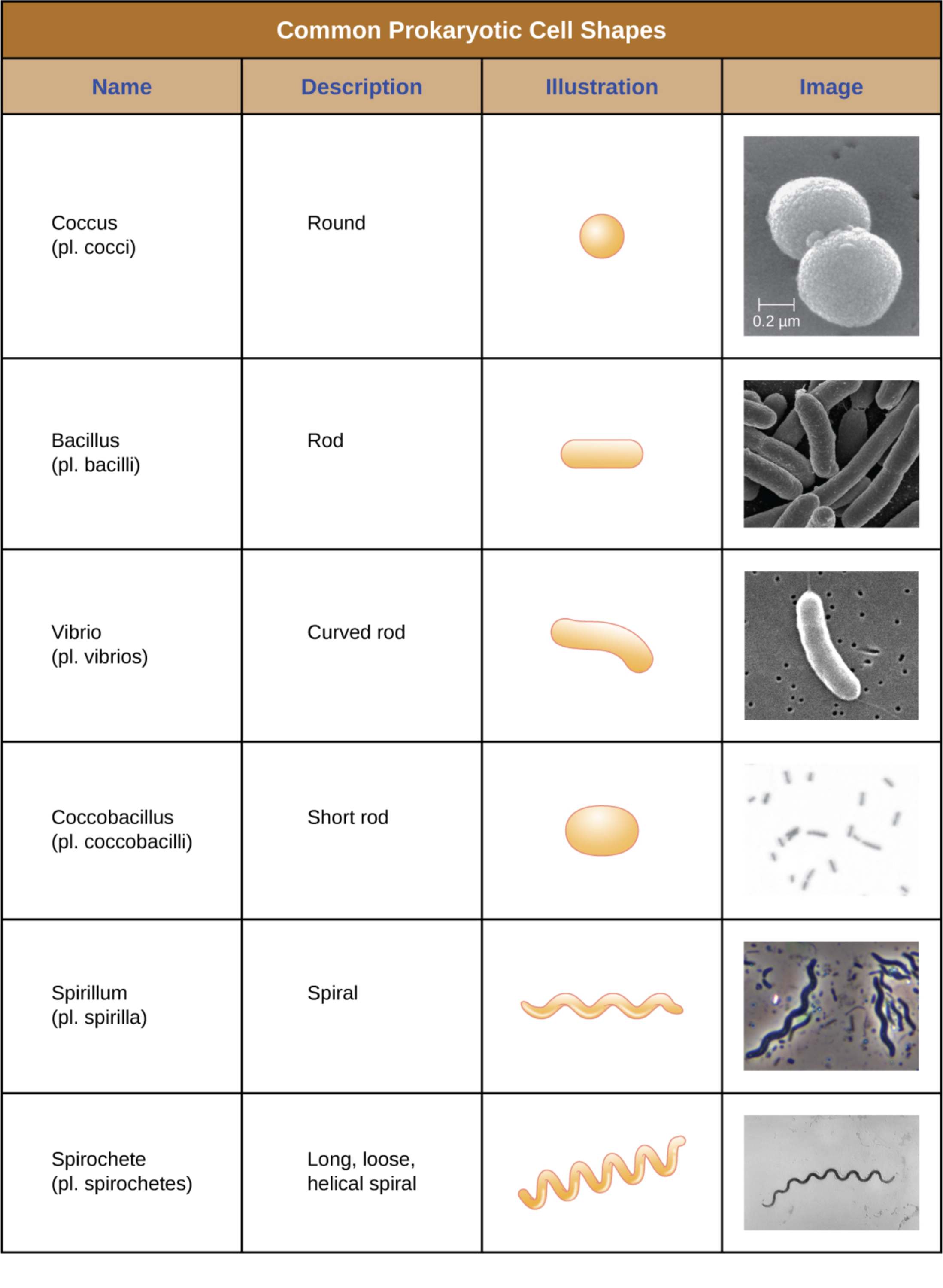

The morphological classification of bacteria is a cornerstone of microbial taxonomy, allowing healthcare professionals and researchers to identify and study various microorganisms. By examining the physical structure and shape of prokaryotic cells, we gain valuable insights into their physiological capabilities and ecological niches. This guide provides a detailed overview of the most common prokaryotic cell shapes, from spherical cocci to complex helical spirochetes, highlighting their biological significance.

Coccus: This morphological term describes prokaryotic cells that are spherical or round in shape. Common examples found in clinical settings include Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae, which often form clusters or chains respectively.

Bacillus: These cells are characterized by a cylindrical or rod-like appearance. This shape is highly efficient for nutrient absorption and is seen in various species such as Escherichia coli and members of the genus Bacillus.

Vibrio: A vibrio cell is essentially a curved rod, often resembling the shape of a comma. These organisms are frequently found in aquatic environments, with Vibrio cholerae being a well-known pathogenic representative.

Coccobacillus: This intermediate shape describes bacteria that are short rods, appearing somewhat between a coccus and a bacillus. Their oval structure is a distinguishing feature for certain respiratory and zoonotic pathogens like Haemophilus influenzae.

Spirillum: These bacteria exhibit a rigid spiral or wavy structure. Unlike other curved forms, spirilla maintain a fixed, corkscrew-like shape that is often propelled by external flagella.

Spirochete: Characterized as a long, loose, and helical spiral, these cells are highly flexible and unique in their movement. They utilize internal axial filaments to move through viscous environments, which is a key trait of the bacteria causing Lyme disease and syphilis.

The Biological Significance of Bacterial Shapes

The shape of a prokaryotic cell is not merely an aesthetic trait but a functional adaptation driven by billions of years of evolution. A cell’s morphology is primarily determined by its peptidoglycan cell wall and the underlying cytoskeleton proteins. These structural components provide the necessary rigidity to withstand osmotic pressure while allowing the cell to interact effectively with its surroundings.

Understanding these shapes is vital for several reasons:

- Nutrient Acquisition: Different shapes optimize the surface-to-volume ratio, which affects how quickly a cell can absorb nutrients and expel waste.

- Motility: Helical and spiral shapes are often better suited for swimming through thick fluids or mucosal membranes.

- Host Interaction: Certain shapes allow bacteria to better adhere to host tissues or evade the immune system.

- Diagnostic Identification: Microscopy and Gram staining allow clinicians to use shape as a primary step in identifying an unknown pathogen.

While most bacteria maintain a consistent shape (monomorphism), some exhibit pleomorphism, changing their shape in response to environmental stressors or nutrient availability. This flexibility can be a survival mechanism, allowing the organism to navigate different physiological conditions within a host. For instance, a rod-shaped bacterium might become spherical to minimize surface exposure when nutrients are scarce.

The physiological implications of these shapes extend to how bacteria grow and divide. Spheres (cocci) may divide in multiple planes, leading to arrangements like diplococci (pairs), tetrads (groups of four), or staphylococci (grape-like clusters). In contrast, bacilli typically divide along a single plane, resulting in single cells, diplobacilli, or long chains known as streptobacilli. This predictable pattern of growth is a key diagnostic feature used in laboratory settings to categorize and eventually treat bacterial infections.

The diverse world of prokaryotic morphology reflects the incredible adaptability of life on a microscopic scale. Whether they are simple spheres or complex spirals, the anatomical structures of these cells are finely tuned to their specific environments. By mastering the terminology and biological significance of these shapes, medical students and professionals can better interpret diagnostic results and understand the life cycles of the microorganisms that impact human health.