In the field of clinical microbiology, the physical arrangement of bacterial cells is a critical diagnostic marker used to identify the causative agents of various infections. These arrangements, which range from simple individual cells to complex chains and clusters, are fundamentally determined by the way a cell divides and whether the daughter cells remain attached afterward. By observing these patterns under a microscope, healthcare professionals can make informed decisions regarding patient treatment and antimicrobial selection.

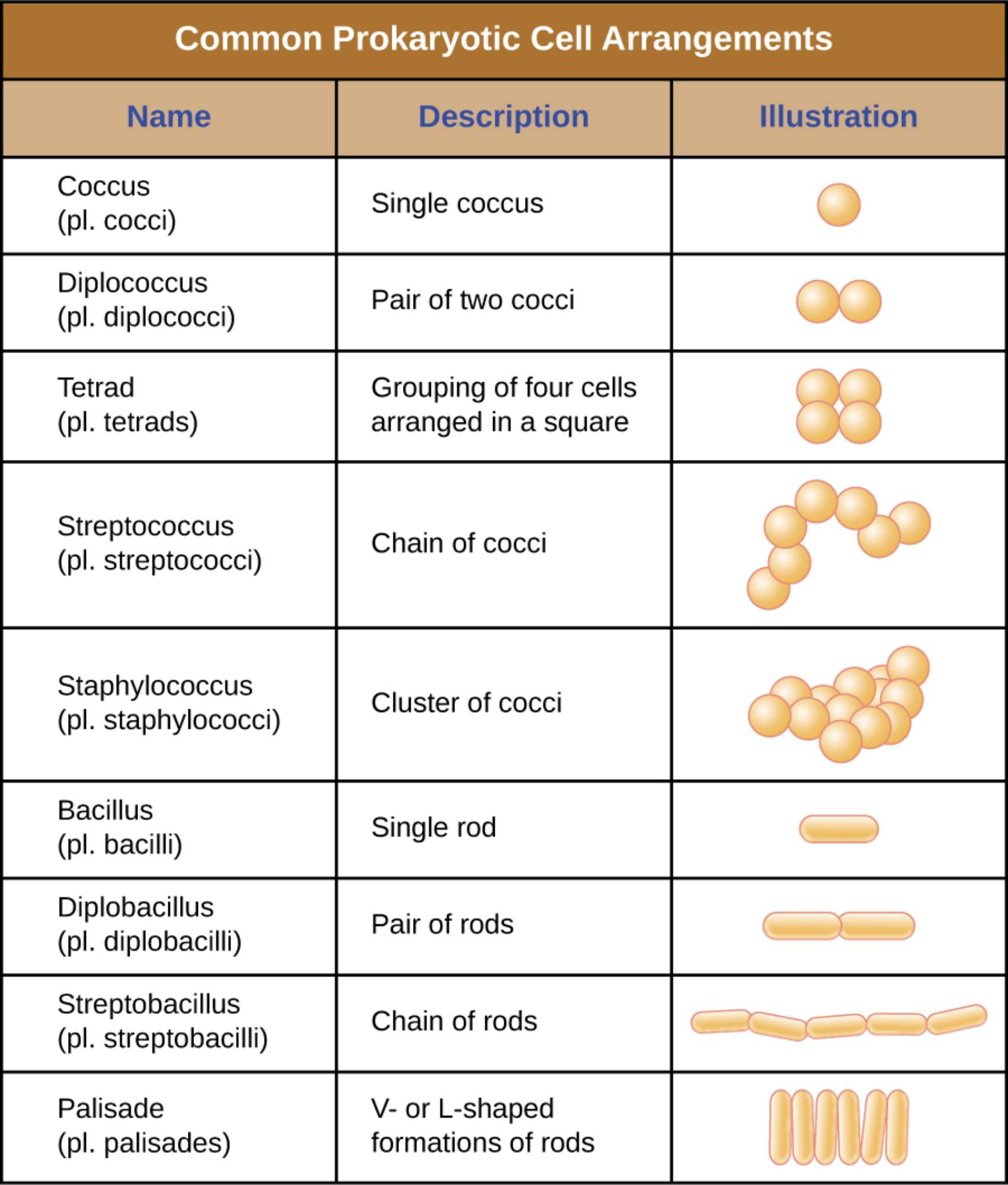

Coccus: This term refers to a single, spherical-shaped bacterium. It is the fundamental building block for all other spherical arrangements seen in microbiology.

Diplococcus: These are pairs of spherical cells that remain attached to one another after a single division event. This specific pattern is a hallmark of certain significant human pathogens, such as Neisseria species.

Tetrad: A tetrad is a grouping of four spherical cells arranged in a precise square or box-like pattern. This arrangement occurs when the bacterial cells divide in two perpendicular planes but do not separate.

Streptococcus: This arrangement consists of a long chain of spherical cells resembling a string of beads. These chains form when a cell divides repeatedly in a single plane and the resulting daughter cells stay linked.

Staphylococcus: These are irregular, grape-like clusters of spherical bacteria. This complex arrangement is the result of cellular division occurring in multiple, random planes of space.

Bacillus: A bacillus is a single rod-shaped bacterium that exists as an independent unit. It is the primary morphological state for many common bacterial species found in nature.

Diplobacillus: This term describes a pair of rod-shaped bacteria joined together end-to-end. This arrangement usually occurs shortly after a single division event before the cells have fully separated.

Streptobacillus: These are chains of rod-shaped bacteria connected linearly. Like streptococci, these form through repeated divisions in a single plane, but with rod-shaped units instead of spheres.

Palisade: A palisade refers to rod-shaped bacteria that are arranged in V- or L-shaped formations or stacked side-by-side like a picket fence. This pattern is created when cells “snap” or fold back against each other during the division process.

The Biological Basis of Bacterial Groupings

The diversity of prokaryotic cell arrangements is a fascinating subject that bridges the gap between anatomy and physiology. While all bacteria are single-celled organisms, the tendency of some species to remain together in specific patterns provides evolutionary and survival advantages. These arrangements are strictly regulated by the cell’s genetic programming and the structural components of its peptidoglycan cell wall, which must be remodeled during every division cycle.

The process of binary fission is the primary method of reproduction for prokaryotes, and it directly dictates the final arrangement of the population. If the cells separate completely after division, they remain as individual units (cocci or bacilli). However, if the attachment proteins and cell wall components keep the daughter cells together, the specific “plane of division” will determine the resulting geometry. For instance, division in one plane creates chains, while division in multiple planes leads to clusters.

The study of these arrangements is vital for several reasons:

- Identification: It is the first step in differentiating between bacterial genera during laboratory analysis.

- Virulence: Certain arrangements, like clusters or chains, can help bacteria evade the host’s immune system or form protective biofilms.

- Growth Dynamics: These patterns often reflect the metabolic state and growth rate of the bacterial population.

- Treatment Selection: Knowing the arrangement often narrows down the list of potential pathogens, allowing for faster empirical therapy.

In a medical setting, the observation of these arrangements through microscopy remains a cornerstone of diagnostic pathology. When a clinician receives a Gram stain report indicating “Gram-positive cocci in clusters,” they immediately recognize the likely presence of Staphylococcus, whereas “Gram-positive cocci in chains” suggests a Streptococcus species. This visual information is often available hours or even days before the results of a definitive culture are finalized.

Physiological Integrity and Structural Planes

The physiological maintenance of these arrangements requires a high degree of coordination. The bacterial cytoskeleton, particularly proteins like FtsZ, determines the location of the division septum. The rigidity of the cell wall ensures that once a pattern like a tetrad or a palisade is formed, it remains stable enough to be visualized during staining procedures. This structural consistency is why morphology and arrangement are considered “monomorphic” traits for most bacterial species, meaning they do not change significantly throughout the organism’s life.

Beyond mere identification, these arrangements also play a role in how bacteria interact with their environment. Rods in a palisade or streptobacilli chains may have different nutrient absorption efficiencies or motility characteristics compared to single bacilli. By living in these temporary multicellular structures, bacteria can potentially share resources or better withstand environmental stressors like desiccation or the presence of antimicrobial agents.

Ultimately, the intricate patterns of prokaryotic life are a testament to the complexity hidden within these “simple” organisms. Whether they appear as elegant chains or chaotic clusters, every arrangement is a product of billions of years of evolutionary refinement. By mastering the terminology and biological significance of these arrangements, the medical community continues to refine its ability to detect, categorize, and treat the vast array of microbial life that impacts human health.