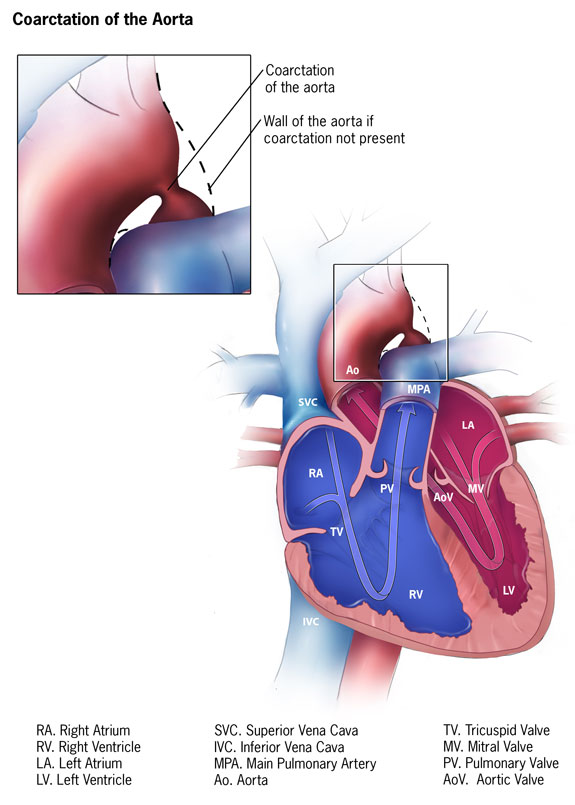

This article delves into Coarctation of the Aorta, a significant congenital heart defect, utilizing the provided anatomical diagram to illustrate its impact on systemic blood flow. We will explore the normal structure and function of the aorta, detail how a localized narrowing compromises blood distribution, and discuss the profound physiological consequences for cardiovascular health, offering a comprehensive overview for medical professionals and interested individuals alike.

Coarctation of the aorta: This label points to a localized narrowing of the aorta, typically occurring near the ductus arteriosus (or ligamentum arteriosum) insertion point. This constriction significantly impedes blood flow to the lower body, while increasing pressure in the upper body.

Wall of the aorta if coarctation not present: This dashed line illustrates the expected smooth and wide internal lumen of the aorta in the absence of coarctation. It highlights the abnormal inward protrusion of the aortic wall that defines the coarctation.

RA. Right Atrium: This chamber receives deoxygenated blood from the body and pumps it into the right ventricle.

RV. Right Ventricle: This chamber pumps deoxygenated blood to the lungs via the main pulmonary artery.

LA. Left Atrium: This chamber receives oxygenated blood from the lungs and pumps it into the left ventricle.

LV. Left Ventricle: This powerful chamber pumps oxygenated blood into the aorta for distribution to the entire body.

SVC. Superior Vena Cava: This large vein carries deoxygenated blood from the upper body (head, neck, arms) to the right atrium.

IVC. Inferior Vena Cava: This large vein carries deoxygenated blood from the lower body and trunk to the right atrium.

MPA. Main Pulmonary Artery: This artery originates from the right ventricle and branches into the pulmonary arteries, carrying deoxygenated blood to the lungs.

PV. Pulmonary Veins: These veins carry oxygenated blood from the lungs back to the left atrium.

Ao. Aorta: The body’s largest artery, originating from the left ventricle, which distributes oxygenated blood to the systemic circulation.

TV. Tricuspid Valve: This valve is located between the right atrium and the right ventricle, preventing backflow of blood into the right atrium during ventricular contraction.

MV. Mitral Valve: This valve is located between the left atrium and the left ventricle, preventing backflow of blood into the left atrium during ventricular contraction.

AoV. Aortic Valve: This valve is located between the left ventricle and the aorta, ensuring one-way flow of blood into the aorta during ventricular contraction.

Coarctation of the Aorta (CoA) is a congenital heart defect characterized by a localized narrowing of the aorta, the body’s largest artery. This constriction, typically found just beyond the origin of the left subclavian artery near the ductus arteriosus, significantly obstructs blood flow from the heart to the lower part of the body. The provided anatomical diagram clearly illustrates this critical narrowing, emphasizing how it deviates from the normal, unobstructed aortic pathway. This defect leads to profound hemodynamic alterations, impacting blood pressure and circulation throughout the body.

The presence of a coarctation creates a pressure gradient across the narrowed segment. Above the coarctation, in the upper body and head, blood pressure is typically elevated. Below the coarctation, blood pressure is lower, and blood flow is often reduced. This disparity in blood pressure is a hallmark clinical sign of CoA and underscores the severity of the obstruction. Without timely diagnosis and intervention, coarctation can lead to serious long-term complications, including systemic hypertension, ventricular dysfunction, and an increased risk of stroke or aortic dissection.

Understanding the precise location and severity of the coarctation, as depicted in the magnified inset, is crucial for comprehending its physiological impact. The contrasting representation of a normal aortic wall highlights the extent of this congenital anomaly.

- Localized Narrowing: A specific constriction in the aorta obstructs blood flow.

- Pressure Gradient: High pressure proximal to the coarctation, low pressure distally.

- Systemic Impact: Affects blood pressure and perfusion throughout the body.

These factors contribute to the complex clinical picture and underscore the need for early recognition and management of Coarctation of the Aorta.

Pathophysiology of Coarctation of the Aorta

Coarctation of the Aorta results from an abnormality in the development of the aortic arch during fetal life. The exact cause is not always clear, but it is thought to involve an abnormal migration of ductal tissue into the aorta, which then constricts. This narrowing typically occurs at the junction of the aortic arch and the descending aorta, often just distal to the left subclavian artery, at the site where the ductus arteriosus (or its remnant, the ligamentum arteriosum) inserts. This specific anatomical location is clearly depicted in the diagram, showing the abrupt inward protrusion of the aortic wall that defines the Coarctation of the aorta.

The primary physiological consequence of CoA is an increase in afterload for the left ventricle due to the resistance to blood flow. To overcome this obstruction and maintain adequate perfusion to the lower body, the left ventricle must pump with greater force, leading to left ventricular hypertrophy (thickening of the heart muscle). This chronic strain can eventually lead to left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure. Additionally, the increased pressure proximal to the coarctation results in systemic hypertension in the upper extremities. Distal to the coarctation, blood flow is reduced, potentially causing symptoms of hypoperfusion in the lower extremities, such as claudication (leg pain with exercise) or cool extremities. The body may attempt to compensate by developing collateral circulation, where smaller blood vessels around the narrowed aorta enlarge to bypass the obstruction and supply blood to the lower body. However, this compensatory mechanism is often insufficient, and the elevated pressure in these collateral vessels can lead to other complications, such as rib notching, visible on chest X-rays.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

The clinical presentation of Coarctation of the Aorta varies significantly depending on the severity of the narrowing, the patient’s age, and the presence of associated cardiac defects. In severe cases, particularly in neonates, CoA can manifest as a life-threatening emergency. Infants may present with signs of heart failure, such as poor feeding, lethargy, respiratory distress, and shock, especially when the ductus arteriosus closes and eliminates a compensatory shunt. In older children and adults, symptoms may be subtle or absent for many years. Common complaints include headaches, nosebleeds, and dizziness (due to hypertension in the upper body), as well as leg pain, weakness, or cold feet (due to reduced perfusion in the lower body). A classic physical finding is a significant difference in blood pressure between the arms and legs (higher in the arms, lower in the legs) and diminished or absent femoral pulses compared to brachial pulses.

Diagnosis of CoA often begins with a thorough physical examination, including blood pressure measurements in all four extremities and palpation of pulses. An echocardiogram is the primary diagnostic tool, providing direct visualization of the coarctation, assessment of its severity, measurement of pressure gradients across the narrowing, and evaluation of left ventricular function. In older children and adults, cardiac MRI or CT angiography can provide more detailed anatomical information, particularly useful for surgical planning. An electrocardiogram (ECG) may show signs of left ventricular hypertrophy, and a chest X-ray might reveal rib notching or an enlarged cardiac silhouette. Early diagnosis is crucial to prevent long-term complications.

Treatment and Long-Term Management

The definitive treatment for Coarctation of the Aorta is correction of the narrowed segment, which can be achieved through surgical repair or catheter-based intervention. The timing of intervention depends on the patient’s age and the severity of the coarctation. In symptomatic neonates, urgent intervention is typically required. Surgical options include resection and end-to-end anastomosis (removing the narrowed segment and rejoining the healthy ends), subclavian flap aortoplasty, or patch aortoplasty. Catheter-based interventions, such as balloon angioplasty (using a balloon to dilate the narrowed segment) often with stent implantation, are increasingly used, particularly in older children and adults, or for re-coarctation after surgery.

Following successful repair, lifelong follow-up with a cardiologist is essential, as patients remain at risk for long-term complications. These can include persistent or recurrent hypertension (even after effective repair), re-coarctation, aneurysm formation at the repair site, and premature coronary artery disease. Regular monitoring of blood pressure, cardiac function, and aortic anatomy is critical. Some patients may require ongoing medication to manage hypertension. Advances in diagnostic imaging and interventional techniques have significantly improved the prognosis for individuals with Coarctation of the Aorta, allowing most to lead full and active lives with appropriate medical care.