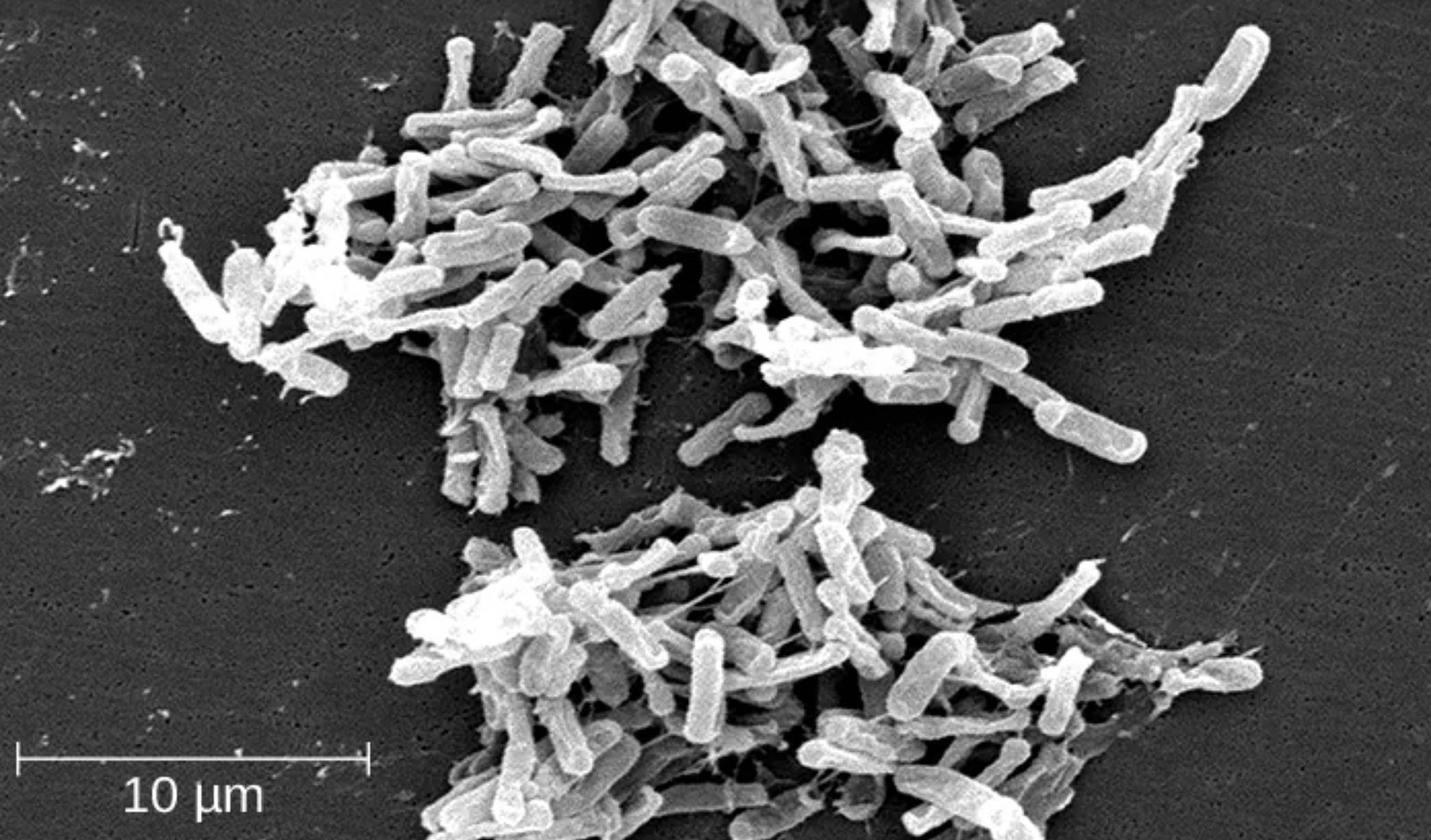

Clostridioides difficile (commonly referred to as C. diff) is a resilient, Gram-positive bacterium that represents a significant challenge in modern healthcare environments. This opportunistic pathogen typically takes advantage of a disrupted gut microbiome—often following broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy—leading to severe gastrointestinal distress, including life-threatening inflammation of the colon. Understanding the morphology and pathogenesis of C. diff is essential for effective diagnosis, infection control, and patient recovery.

10 μm: This scale bar represents ten micrometers in length, providing a crucial visual reference for the microscopic size of the bacterial colony. It demonstrates that individual rod-shaped bacilli are extremely small, usually ranging from 3 to 6 micrometers in length, which allows them to colonize the intricate folds of the human intestinal lining.

Clostridioides difficile is an anaerobic, spore-forming bacillus that is a leading cause of healthcare-associated infections worldwide. Under normal conditions, a healthy and diverse community of gut microbes prevents C. diff from proliferating through a process known as colonization resistance. However, when antibiotics eradicate these “friendly” bacteria, C. diff can flourish, leading to a state of gut dysbiosis where the pathogen dominates the intestinal environment.

The bacterium is particularly notorious for its ability to produce highly resilient endospores. These spores are resistant to common disinfectants, heat, and even the acidic environment of the stomach. Once they reach the large intestine, the spores germinate into vegetative cells that begin to release potent toxins. This survival mechanism makes the bacterium exceptionally difficult to eliminate from hospital surfaces and allows it to persist in the environment for months.

Clinically, the severity of the infection can range from mild diarrhea to a catastrophic inflammatory condition. In the most severe cases, the toxins cause extensive damage to the intestinal epithelium, resulting in the formation of “false membranes” composed of inflammatory debris and dead cells. This condition is a hallmark of the disease and requires aggressive medical intervention to prevent complications like toxic megacolon or perforation of the bowel.

Key risk factors for developing a Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) include:

- Recent use of broad-spectrum antibiotics (such as clindamycin or fluoroquinolones).

- Age over 65 years, as the immune system and gut flora may be less resilient.

- Recent or prolonged hospitalization or residence in a long-term care facility.

- The use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) that reduce stomach acidity.

Pathogenesis and the Role of Bacterial Toxins

The virulence of Clostridioides difficile is primarily driven by the production of two large exotoxins: Toxin A (an enterotoxin) and Toxin B (a cytotoxin). These toxins target the Rho GTPases within human intestinal cells, disrupting the cellular cytoskeleton and breaking down the tight junctions between cells. This lead to increased vascular permeability, massive fluid secretion, and the recruitment of neutrophils, which collectively cause the characteristic watery diarrhea associated with the infection.

In advanced stages, the cumulative damage leads to pseudomembranous colitis, a severe form of inflammation where yellow-white plaques appear on the surface of the colon. While some individuals may experience asymptomatic carriage, where the bacteria reside in the gut without causing illness, they can still shed spores into the environment, posing a risk to others. The inflammatory response is so robust that it often causes systemic symptoms, including high fever, elevated white blood cell counts, and severe abdominal cramping.

Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment Strategies

Diagnosis is typically confirmed through stool tests that detect the presence of C. diff toxins or the bacterial gene responsible for producing them (using PCR). Because the bacteria are part of the normal flora for a small percentage of people, clinicians must differentiate between mere colonization and active infection by correlating laboratory results with clinical symptoms. Imaging, such as a CT scan, may also be used to assess the thickness of the colonic wall in suspected cases of severe colitis.

Treatment has evolved significantly as the bacterium has become more resistant to traditional therapies. Currently, oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin are the preferred first-line antibiotics because they remain concentrated within the gut. For patients with multiple recurrences, a Fecal Microbiota Transplant (FMT) has emerged as a highly effective therapy. This procedure involves introducing stool from a healthy donor into the patient’s colon to restore a healthy microbial balance and provide long-term protection against reinfection.

Preventing the spread of C. diff requires a combination of strict hand hygiene—using soap and water rather than alcohol-based sanitizers, which do not kill spores—and rigorous environmental cleaning with bleach-based agents. Furthermore, antimicrobial stewardship programs are vital to ensure that antibiotics are only used when absolutely necessary, thereby preserving the protective barrier of the natural human microbiome. Through these combined efforts, the medical community continues to combat this formidable and persistent gastrointestinal pathogen.