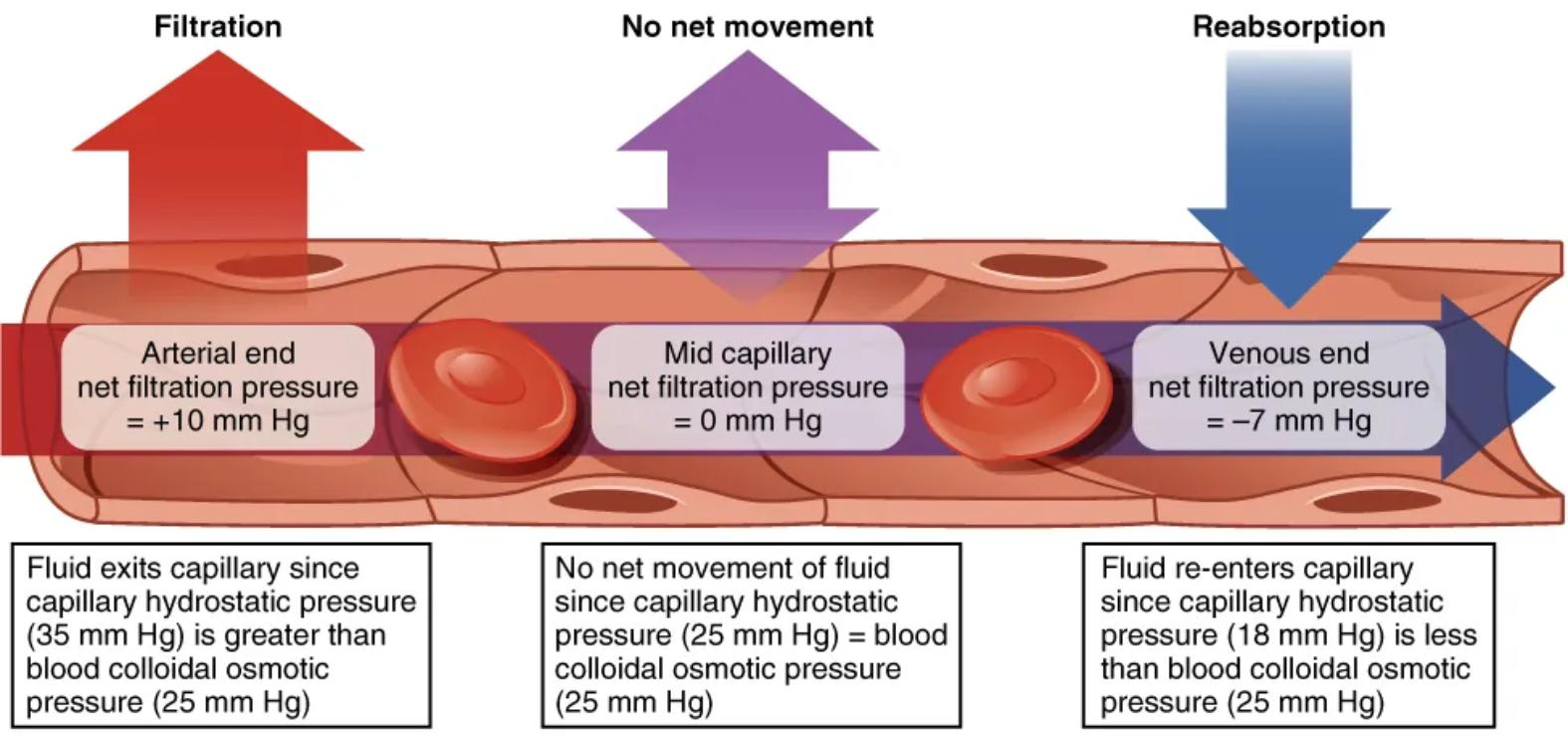

Capillaries, the body’s smallest blood vessels, are the primary sites for the exchange of nutrients, oxygen, and waste products between blood and interstitial fluid. This detailed diagram illustrates the critical process of capillary exchange, driven by the interplay of hydrostatic and osmotic pressures. It beautifully demonstrates how fluid movement changes along the length of a capillary, from filtration at the arterial end to reabsorption at the venous end. Grasping these dynamics is fundamental to understanding tissue perfusion, fluid balance, and the pathophysiology of conditions like edema.

Filtration: Movement of fluid out of the capillary.

Filtration occurs when the net filtration pressure is positive, meaning fluid is forced out of the capillary into the interstitial space. This process is dominant at the arterial end of the capillary where capillary hydrostatic pressure (CHP) is higher than blood colloidal osmotic pressure (BCOP), pushing water and small solutes into the surrounding tissues, delivering nutrients and oxygen to cells.

No net movement: Equilibrium where there is no overall fluid shift.

At the midpoint of the capillary, a state of dynamic equilibrium exists where there is no net movement of fluid. This occurs because the capillary hydrostatic pressure (CHP) and the blood colloidal osmotic pressure (BCOP) are approximately equal, balancing the forces pushing fluid out and pulling fluid in.

Reabsorption: Movement of fluid back into the capillary.

Reabsorption occurs when the net filtration pressure is negative, leading to fluid re-entering the capillary from the interstitial space. This process is prominent at the venous end of the capillary where the blood colloidal osmotic pressure (BCOP) becomes greater than the capillary hydrostatic pressure (CHP), drawing waste products and excess fluid back into the bloodstream for removal.

Arterial end: The segment of the capillary closer to the arteriole.

At the arterial end of the capillary, the blood pressure, specifically the capillary hydrostatic pressure (CHP), is highest (e.g., 35 mm Hg). This high pressure is the primary driving force for filtration, pushing fluid rich in oxygen and nutrients out of the capillary and into the surrounding interstitial fluid to nourish the tissues. The net filtration pressure here is positive, typically around +10 mm Hg.

Mid capillary: The central segment of the capillary.

Near the midpoint of the capillary, the capillary hydrostatic pressure (CHP) has decreased significantly (e.g., to 25 mm Hg) due to fluid loss and resistance. At this point, the CHP often equals the blood colloidal osmotic pressure (BCOP) (e.g., 25 mm Hg), resulting in no net movement of fluid across the capillary wall. This represents a transition zone in the fluid exchange process.

Venous end: The segment of the capillary closer to the venule.

At the venous end of the capillary, the capillary hydrostatic pressure (CHP) has further decreased (e.g., to 18 mm Hg), becoming lower than the blood colloidal osmotic pressure (BCOP) (e.g., 25 mm Hg). This pressure gradient favors reabsorption, meaning fluid, along with metabolic waste products, is drawn back into the capillary from the interstitial space. The net filtration pressure here is negative, typically around -7 mm Hg.

Capillary exchange is a vital physiological process that ensures the continuous supply of oxygen and nutrients to tissues while simultaneously removing metabolic waste products. This diagram elegantly illustrates Starling’s forces, the opposing pressures that govern fluid movement across the capillary walls: capillary hydrostatic pressure (CHP) and blood colloidal osmotic pressure (BCOP). These forces orchestrate a dynamic equilibrium, ensuring that tissues are adequately perfused without excessive fluid accumulation in the interstitial space.

At the arterial end of the capillary, the higher capillary hydrostatic pressure, driven by the heart’s pumping action, is typically greater than the blood colloidal osmotic pressure. This pressure differential results in net filtration, where fluid, along with dissolved substances like oxygen, glucose, and amino acids, is forced out of the capillary and into the surrounding interstitial fluid. This effectively bathes the tissue cells, providing them with essential resources.

As blood flows along the capillary, several changes occur. The capillary hydrostatic pressure gradually decreases due to both fluid loss and frictional resistance within the vessel. Concurrently, the blood colloidal osmotic pressure remains relatively constant or slightly increases due to the retention of large plasma proteins within the capillary. By the venous end of the capillary, the capillary hydrostatic pressure drops below the blood colloidal osmotic pressure, leading to net reabsorption. Here, fluid, carrying metabolic waste products like carbon dioxide and urea, is drawn back into the capillary.

This efficient balance of filtration and reabsorption is crucial for maintaining fluid homeostasis within the body. Disruptions to these pressures can lead to significant clinical issues. For example, an increase in capillary hydrostatic pressure (as seen in heart failure) or a decrease in blood colloidal osmotic pressure (due to liver disease causing low plasma protein synthesis) can both lead to excessive net filtration and result in edema, the swelling of tissues due to fluid accumulation. Conversely, severe dehydration can lead to reduced fluid filtration, impairing nutrient delivery to cells.

In conclusion, the capillary exchange mechanism, as clearly depicted in this diagram, is a cornerstone of cardiovascular and fluid physiology. The precise interplay between capillary hydrostatic pressure and blood colloidal osmotic pressure dictates the movement of fluid across capillary walls, ensuring that tissues are nourished and waste products are removed. A thorough understanding of these Starling forces is indispensable for comprehending normal physiological function and for identifying the underlying causes of fluid imbalance disorders.