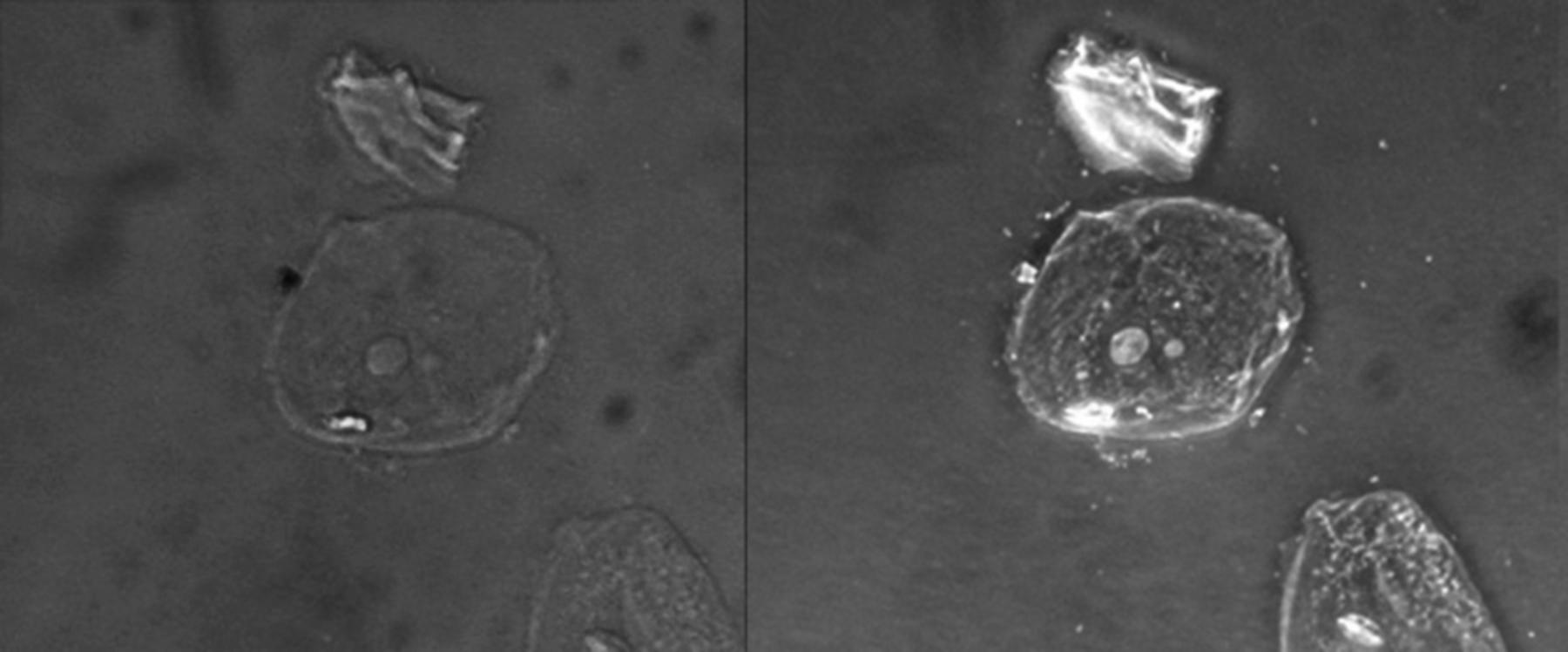

Microscopy is a cornerstone of medical diagnostics and biological research, enabling the detailed observation of cellular structures that are otherwise invisible to the naked eye. This visual comparison highlights the distinct capabilities of two fundamental imaging techniques—brightfield and phase-contrast microscopy—when analyzing unstained simple squamous epithelial cells. By examining these images side-by-side, we can appreciate how manipulating light properties allows healthcare professionals to visualize transparent biological specimens without the need for chemical dyes that might alter or kill the cells.

Brightfield Image (Left): This represents the standard form of optical microscopy where light is transmitted directly through the specimen. Because the biological tissue is unstained and translucent, there is very little contrast between the cell and the surrounding medium, rendering the structures nearly invisible and difficult to analyze.

Phase-Contrast Image (Right): This image utilizes an optical technique that converts phase shifts in light passing through a transparent specimen into brightness changes in the image. This process enhances the contrast of the cell borders and internal organelles, causing the cell to appear to “glow” against the dark background and revealing details like the nucleus.

Simple Squamous Epithelial Cells: These are the primary subjects located in the center and bottom right of the viewing field. They are characterized by their flattened, scale-like appearance and a central nucleus, serving as a thin barrier in various anatomical locations to facilitate diffusion and filtration.

Acellular Debris: This irregular artifact is located above the central cell in both images. It represents non-living particulate matter, which is common in slide preparations and can be distinguished from viable cellular material more easily using high-contrast imaging techniques.

The Evolution of Cellular Visualization

The ability to visualize cells is fundamental to pathology, histology, and cytology. In a clinical laboratory setting, time is often of the essence, and the preservation of the specimen’s natural state is sometimes required. Standard brightfield microscopy, while effective for stained specimens, falls short when viewing live or unstained transparent cells. This is because the cytoplasm of an animal cell has a refractive index very similar to water; light passes through it without being significantly absorbed or deflected, resulting in the “ghost-like” faint image seen on the left.

To overcome this limitation without killing the cells via chemical staining (fixation), Dutch physicist Frits Zernike developed phase-contrast microscopy in the 1930s. This technique exploits the fact that light slows down slightly when passing through biological material compared to the surrounding medium. Although the human eye cannot detect these phase shifts, the phase-contrast microscope uses a special condenser and objective lens to convert these invisible phase differences into visible variations in light intensity (amplitude).

This optical manipulation is crucial for various medical applications. It allows for the immediate assessment of cell viability, motility, and integrity. For example, during a urinalysis or a sperm count, technicians often rely on contrast-enhancing techniques to differentiate between different cell types and artifacts without the delay of staining protocols.

Key advantages of phase-contrast microscopy include:

- High Contrast: It reveals intracellular structures like nuclei and organelles in sharp relief.

- Live Cell Imaging: It allows for the observation of living cells and biological processes (like cell division) in real-time.

- Minimal Preparation: It eliminates the need for time-consuming fixation and staining procedures.

- Artifact Detection: It helps distinguish between relevant biological cells and non-relevant debris.

Anatomical Characteristics of Simple Squamous Epithelium

The cells featured in the image are simple squamous epithelial cells, likely obtained from a buccal smear (a cheek swab). Anatomically, these cells are defined by their thinness and platelike structure. In the human body, this specific morphology is functionally critical. Because they are so thin, they allow for the rapid passage of substances. For instance, they line the alveoli of the lungs to facilitate oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange, and they form the endothelium of blood capillaries where nutrient transfer occurs.

In the phase-contrast image (right), the nucleus is clearly visible as a denser, circular structure within the cytoplasm. The nucleus houses the cell’s genetic material (DNA) and coordinates cellular activities such as growth and metabolism. The cell membrane is also sharply defined, marking the boundary between the intracellular environment and the extracellular space. In a clinical context, observing the nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio and the regularity of the cell border is essential for detecting abnormalities, such as precancerous changes.

Physiology of Light Interaction in Microscopy

The striking difference between the two images is a lesson in optical physics applied to physiology. In the brightfield image, the light waves pass through the thin epithelial cell with almost no obstruction. The amplitude (brightness) of the light remains largely unchanged, so our eyes perceive the cell as transparent. This is why brightfield microscopy is typically reserved for specimens that have been stained with dyes like Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), which artificially darken specific cell parts to create contrast.

In contrast, the phase-contrast image reveals the refractive index variations within the cell. The nucleus is denser than the surrounding cytoplasm, and the cytoplasm is denser than the mounting medium. As light passes through these different densities, it is shifted out of phase. The phase-contrast microscope amplifies this shift. The result is an image where the cell membrane and nucleus appear darker or brighter (depending on the specific setup) than the background. This “halo” effect, often seen around the edges of the cell in phase-contrast images, is an optical artifact but serves as a helpful outline for identifying the cell’s perimeter.

Conclusion

The comparison between brightfield and phase-contrast microscopy underscores the importance of technological innovation in medical science. While the simple squamous epithelial cells remain biologically identical in both frames, the method of visualization determines how much information can be extracted. The ability to see unstained, transparent cells with high clarity allows clinicians and researchers to perform rapid, non-destructive analysis, essential for diagnosing conditions ranging from urinary tract infections to male infertility, and for understanding fundamental cellular biology.