Bacterial sporulation is a sophisticated developmental process that allows certain Gram-positive bacteria to transition from an active growth state into a highly resilient, dormant form known as an endospore. This biological “escape hatch” is triggered by extreme environmental stress, such as nutrient depletion or desiccation, ensuring the survival of the organism’s genetic blueprint for years or even centuries. Understanding the intricate steps of sporulation is crucial in clinical medicine and public health, as endospores are notoriously resistant to standard disinfection and sterilization protocols.

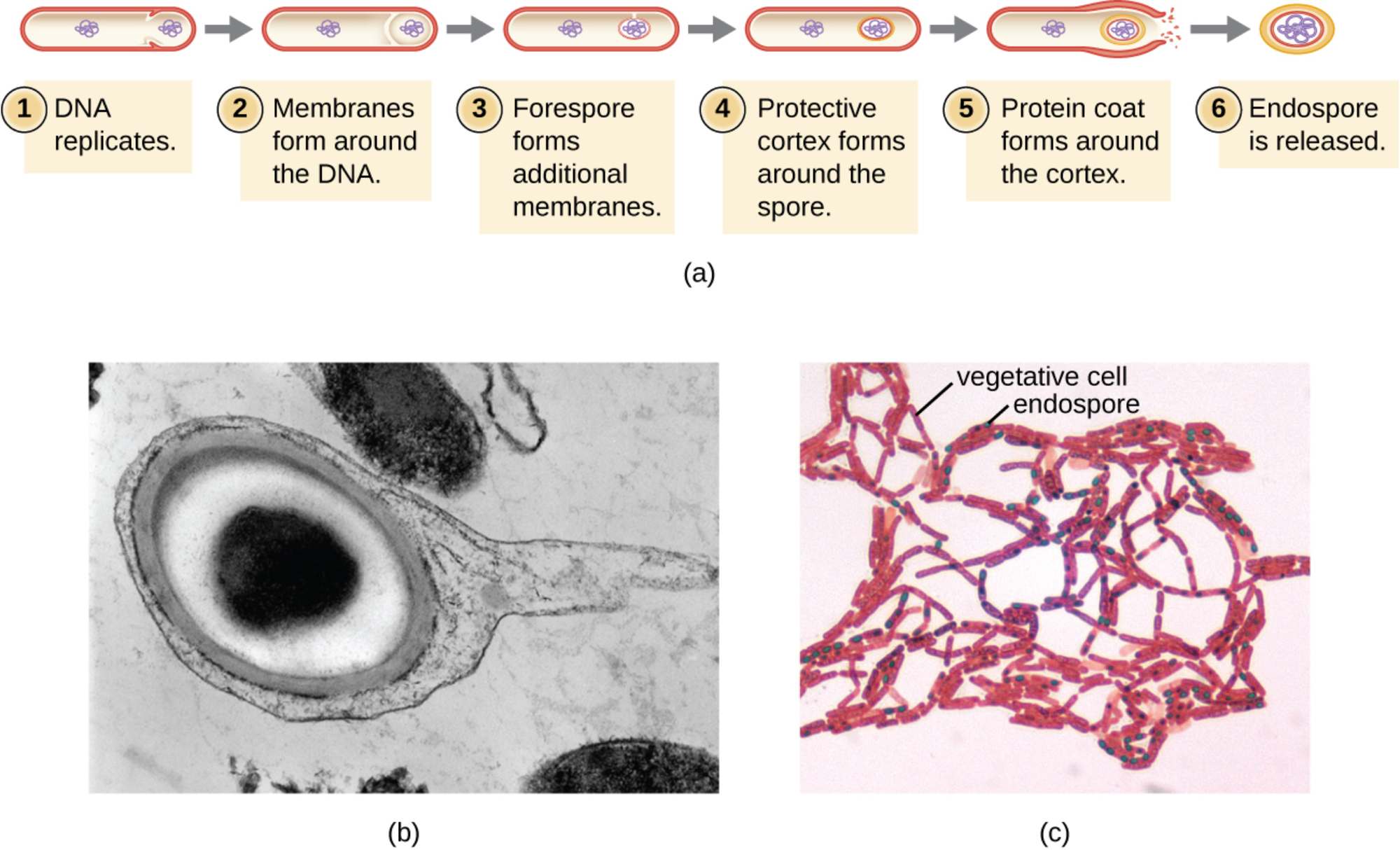

DNA replicates: This initial step involves the duplication of the bacterial chromosome to ensure that both the mother cell and the developing spore have a complete set of genetic instructions. The replicated DNA is then partitioned at one end of the cell through asymmetric division.

Membranes form around the DNA: Following replication, the plasma membrane of the mother cell begins to invaginate, sequestering the newly copied DNA into a separate compartment. This stage marks the physical commitment of the cell to the sporulation pathway.

Forespore forms additional membranes: The mother cell eventually engulfs the smaller compartment, creating a “cell within a cell” known as a forespore. This results in the forespore being surrounded by a unique double-membrane system that provides a foundation for the addition of protective layers.

Protective cortex forms around the spore: Between the two membranes of the forespore, a thick layer of specialized peptidoglycan is deposited to form the cortex. This layer is essential for the extreme dehydration of the spore core, which contributes significantly to its resistance to heat and radiation.

Protein coat forms around the cortex: A dense, multi-layered coat made of specialized proteins is synthesized and assembled around the cortex. This hard outer shell acts as a chemical and enzymatic barrier, protecting the delicate internal machinery from toxins and digestive enzymes.

Endospore is released: Once the endospore is fully mature, the mother cell undergoes programmed lysis (disintegration), releasing the spore into the environment. The free endospore remains metabolically inactive until it encounters favorable conditions that trigger germination back into a vegetative state.

Vegetative cell: This term refers to the active, metabolically functional state of the bacterium where it is capable of growth and reproduction. Vegetative cells are relatively fragile compared to endospores and are easily killed by common antibiotics and disinfectants.

Endospore: The endospore is the final, dormant product of sporulation, characterized by its extraordinary resistance to environmental extremes. It contains a dehydrated core, stabilized by dipicolinic acid and calcium ions, which protects the DNA from damage during prolonged dormancy.

The Biological Significance of Sporulation

The transition from a vegetative cell to an endospore is one of the most remarkable examples of cellular differentiation in the microbial world. Unlike fungal spores, which are primarily reproductive, bacterial endospores are strictly survival structures. This process is typically observed in specific genera, most notably Bacillus and Clostridium, which are responsible for several significant human diseases.

During sporulation, the cell undergoes a massive metabolic shift, redirecting its energy toward building the multi-layered defenses of the spore. The core of the endospore becomes highly dehydrated, reaching a state where chemical reactions almost entirely cease. This state of suspended animation allows the organism to survive boiling, freezing, ultraviolet radiation, and exposure to harsh chemicals that would instantly destroy a normal cell.

The clinical and industrial importance of endospores cannot be overstated, particularly in the following areas:

- Sterilization Validation: High-heat-resistant spores are used as biological indicators to ensure that autoclaves and other sterilization equipment are functioning correctly.

- Infection Control: The resilience of spores necessitates the use of specialized “sporicidal” agents in hospital settings to prevent the spread of healthcare-associated infections.

- Food Safety: Heat-resistant spores of organisms like Clostridium botulinum can survive improper canning processes, leading to life-threatening cases of botulism.

- Biodefense: The stability and ease of dispersal of certain spores, such as Bacillus anthracis, make them a primary concern in the study of biological threats.

Anatomical Defense and Pathogenic Relevance

The anatomical structure of a mature endospore is a fortress of biological layers. The innermost core contains the DNA, ribosomes, and specialized small acid-soluble proteins (SASPs) that saturate the DNA to prevent damage from UV light and chemicals. Surrounding the core is the inner membrane, followed by the thick cortex, an outer membrane, and the multi-layered protein coat. Some species even possess an additional outermost layer called the exosporium.

In medical practice, the most challenging aspect of endospores is their role in pathogenic persistence. For example, Clostridium difficile produces spores that can persist on hospital surfaces for months, resisting standard alcohol-based hand sanitizers. Patients often ingest these spores, which then germinate in the gut once the protective normal flora has been disrupted by antibiotic use. This cycle makes C. diff infections exceptionally difficult to eradicate and prone to recurrence.

Furthermore, the physiology of germination is as complex as sporulation itself. When an endospore senses the presence of specific nutrients, such as amino acids or sugars, it initiates a rapid rehydration process. The protective layers are shed, metabolic activity resumes, and the organism returns to its vegetative state, ready to colonize and potentially cause disease. This ability to cycle between extreme dormancy and rapid growth is why spore-forming bacteria remain some of the most successful and dangerous organisms in the history of medicine.

The process of sporulation is a testament to the evolutionary ingenuity of prokaryotic life. By investing energy into a nearly indestructible dormant form, certain bacteria have secured their survival across geological timescales and through the most rigorous attempts at human intervention. Continued research into the molecular triggers of sporulation and germination is essential for developing new strategies to combat spore-related diseases and improve global healthcare outcomes.