Bacterial pili are specialized proteinaceous appendages that extend from the cell surface, playing pivotal roles in attachment, motility, and the horizontal transfer of genetic material. These structures are essential for the survival and pathogenicity of various bacterial species, facilitating critical interactions between microbial cells and their host environments. By understanding the mechanical and biochemical properties of pili, medical professionals can better comprehend the mechanisms of bacterial infection and the rapid spread of antimicrobial resistance.

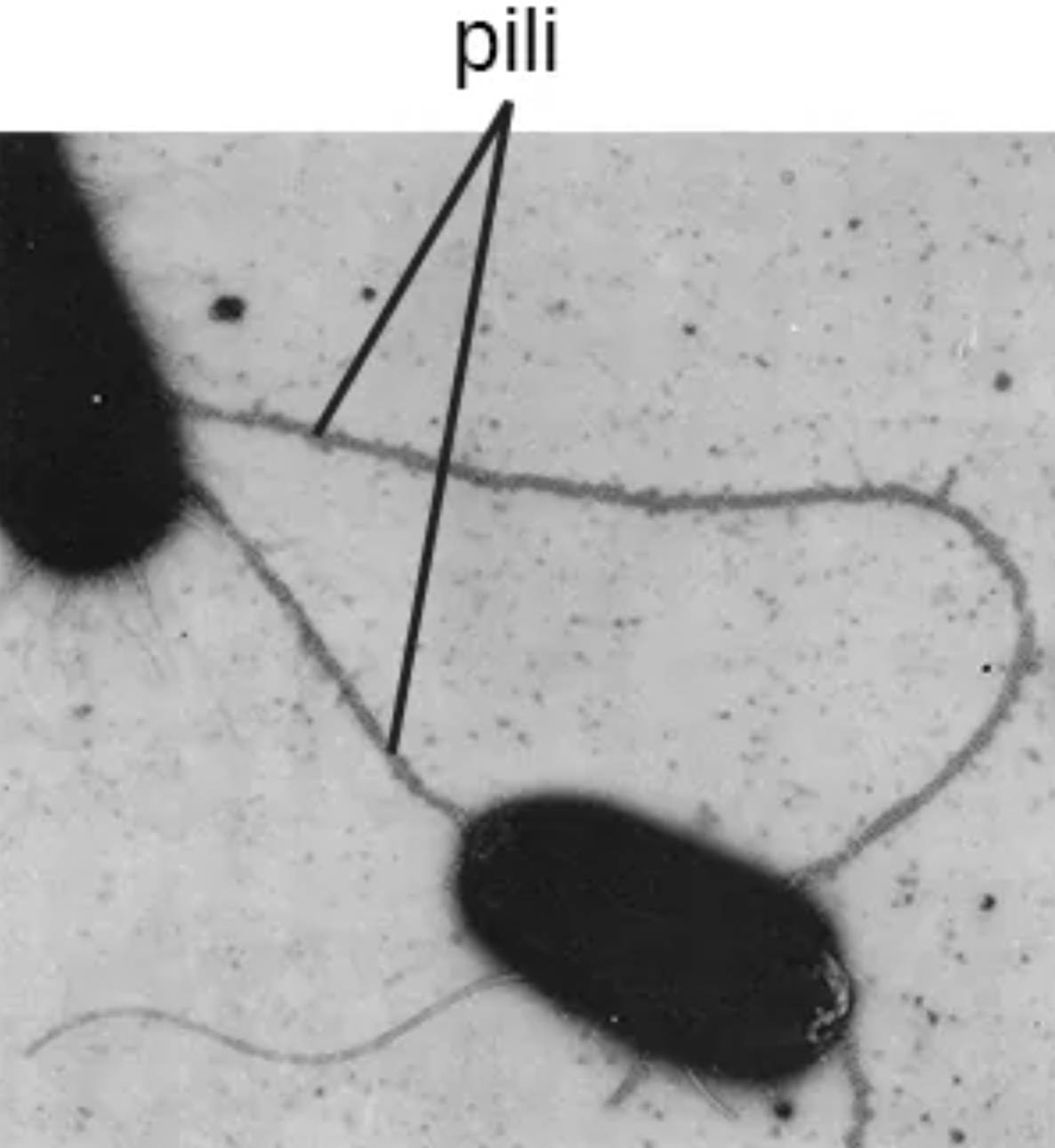

pili: These are long, hair-like protein structures that extend from the bacterial surface to facilitate attachment to other cells or surfaces. Unlike shorter fimbriae, pili are typically fewer in number and are often involved in specialized processes such as bacterial conjugation.

Bacteria utilize a variety of surface appendages to navigate and thrive in complex biological niches. Among these, fimbriae and pili are the most prominent, though they serve distinct functions based on their length, quantity, and molecular composition. While fimbriae are generally short, numerous, and primarily used for adhesion to mucosal surfaces, pili are longer, less abundant, and facilitate more complex interactions.

The image provided showcases pili as elongated filaments that can even bridge the gap between two separate bacterial cells. This bridging is often a prerequisite for the exchange of plasmids, which are extra-chromosomal DNA fragments. This process is a primary driver of microbial evolution and the dissemination of survival traits across populations.

Key functions and characteristics of bacterial pili include:

- Facilitating conjugation for the exchange of genetic information between donor and recipient cells.

- Providing “twitching motility,” a form of surface movement powered by the rapid extension and retraction of the pilus.

- Acting as virulence factors by enabling pathogens to adhere firmly to host tissues, such as the lining of the urinary tract.

- Contributing to the structural integrity of a biofilm, protecting the microbial community from host defenses and antibiotics.

The study of these appendages is vital in clinical microbiology, as they are often the first point of contact between a pathogen and the human body. Disruption of pilus function or assembly represents a promising target for new classes of antibacterial therapies.

Anatomical and Physiological Mechanisms

The assembly of a bacterial pilus is a complex physiological process involving the polymerization of individual protein subunits known as pilin. These subunits are synthesized in the cytoplasm and transported across the plasma membrane, where they are organized into a helical structure. The tip of the pilus often contains specialized adhesin proteins that determine the specificity of the attachment, allowing the bacterium to recognize and bind to specific host cell receptors.

One of the most medically significant roles of pili is in the process of horizontal gene transfer. Through a specialized structure called the F-pilus or sex pilus, a donor bacterium can physically connect to a recipient bacterium. Once a stable connection is established, the pilus retracts to bring the cells into close contact, allowing for the transfer of genetic material. This mechanism is frequently responsible for the spread of multi-drug resistance genes, enabling previously susceptible bacteria to survive exposure to common antibiotics.

In addition to genetic exchange, pili contribute to the development of complex multicellular communities. When bacteria colonize a surface, pili help them aggregate and form a protective matrix. This structure shields the internal members of the colony from environmental stressors, such as changes in pH or the presence of immune cells like neutrophils. Consequently, bacteria that produce robust pili are often more difficult to eradicate in chronic clinical infections, such as those involving catheters or prosthetic joints.

The evolution of bacterial pili highlights the remarkable adaptability of microorganisms. These protein structures serve as the “arms” of the cell, allowing it to reach out, communicate, and anchor itself within a host. By continuing to investigate the molecular pathways that govern pilus formation, medical science moves closer to developing innovative strategies to block bacterial adhesion and halt the progression of infectious diseases at their earliest stages.