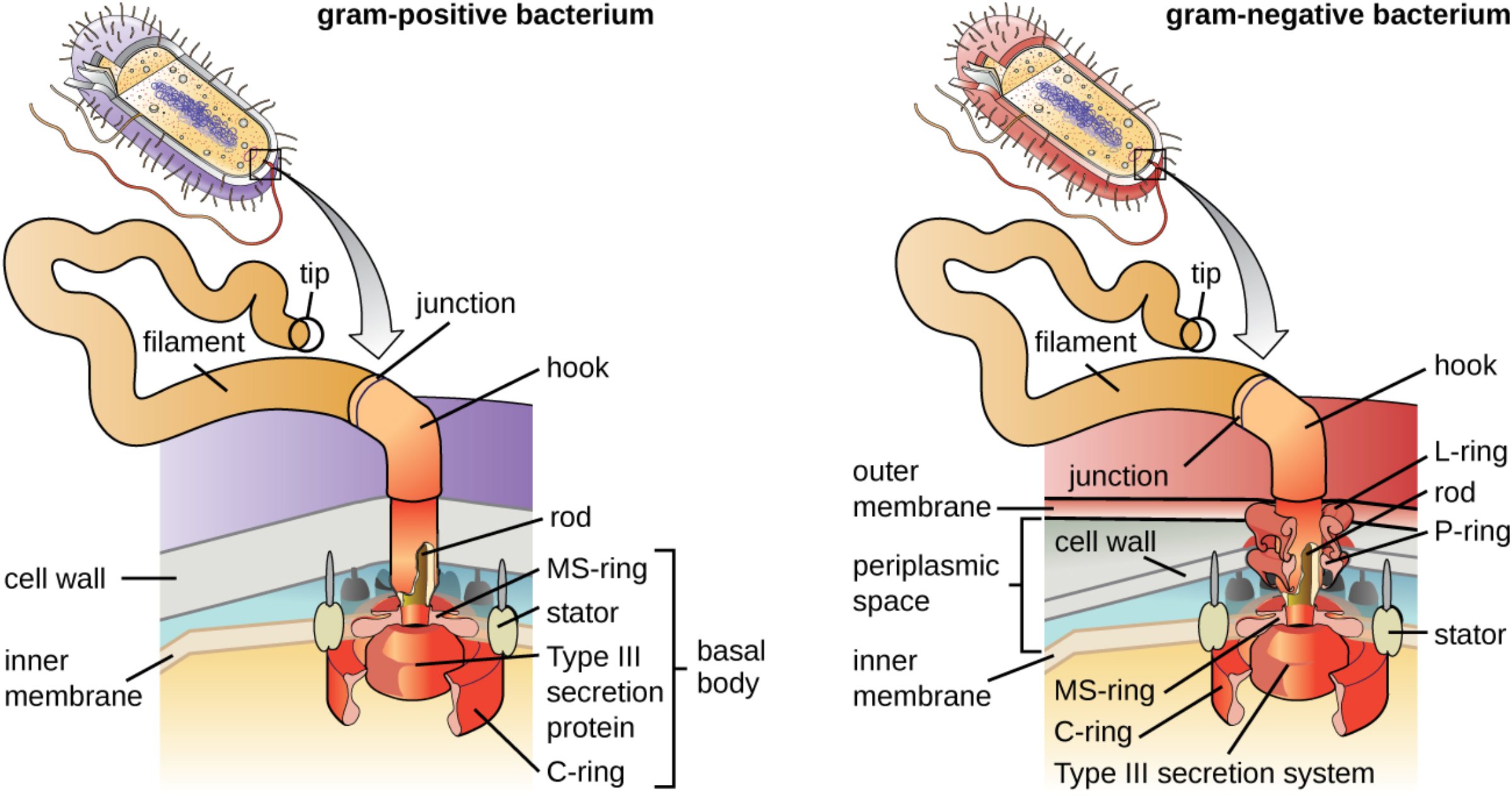

The bacterial flagellum is a biological masterpiece of molecular engineering, functioning as a microscopic rotary motor that propels bacteria through their aqueous environments. This complex apparatus is composed of three primary sections: the basal body, which acts as the motor anchored in the cell envelope; the hook, serving as a flexible universal joint; and the filament, the long external propeller. Understanding the structural differences between the flagella of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria is essential for medical professionals studying microbial pathogenesis and the mechanisms of cellular movement.

Tip: The tip is a specialized protein cap located at the very end of the flagellar filament. It is essential for the assembly process, as it guides the incorporation of new flagellin subunits at the distal end of the growing structure.

Filament: The filament is the long, rigid, whip-like structure that extends from the cell body into the surrounding medium. It is composed of thousands of repeating flagellin subunits and functions as the primary propeller for bacterial movement.

Junction: The junction represents the transitional region where the rigid filament meets the more flexible hook. This area is critical for maintaining mechanical integrity while the flagellum rotates at high speeds.

Hook: The hook is a short, curved segment that connects the filament to the basal body assembly. It functions as a universal joint, converting the torque generated by the cytoplasmic motor into the rotational movement of the external propeller.

Rod: The rod is a central proteinaceous axle that passes through the rings of the basal body. It serves as the transmission shaft, transferring rotational energy from the motor located in the inner membrane to the external components.

L-ring: The L-ring is a structural component found exclusively in Gram-negative bacteria, anchored within the lipopolysaccharide layer of the outer membrane. It acts as a bushing, allowing the rod to rotate freely through the lipid bilayer.

P-ring: The P-ring is situated within the peptidoglycan cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria. It provides vital support and stabilizes the rod assembly as it penetrates the structural scaffolding of the cell.

MS-ring: The MS-ring is an integral component of the basal body that is anchored directly into the cytoplasmic (inner) membrane. It provides a base for the rotor and is present in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative species.

C-ring: The C-ring, or switch complex, is located on the cytoplasmic face of the inner membrane. It is responsible for switching the direction of rotation in response to environmental signals and functions as the rotor.

Stator: The stator is a set of stationary protein complexes that surround the rotor in the inner membrane. It harvests energy from ion gradients to generate the torque required for the motor’s rotation.

Type III secretion protein/system: This system is located at the base of the flagellum and is responsible for exporting flagellar subunits through the central channel to the growing tip. It is evolutionarily linked to specialized secretion systems used by pathogens to inject toxins into host cells.

Basal body: The basal body is the entire motor assembly anchored within the bacterial cell envelope. It consists of the rod, various rings, and the motor proteins required for flagellar rotation.

Outer membrane: The outer membrane is a secondary lipid bilayer present only in Gram-negative bacteria. It contains lipopolysaccharides and provides the anchor for the L-ring of the basal body.

Cell wall: The cell wall is the peptidoglycan layer that gives the bacterium its shape and structural strength. In Gram-positive bacteria, this layer is significantly thicker than in Gram-negative species, requiring a different basal body configuration.

Periplasmic space: This region is the aqueous compartment located between the inner and outer membranes of Gram-negative bacteria. It houses the P-ring and is a site for various metabolic and transport activities.

Inner membrane: The inner membrane is the primary phospholipid bilayer that encloses the cytoplasm. It serves as the foundation for the entire flagellar motor assembly and maintains the ion gradients used to power rotation.

The Mechanical Logic of Bacterial Locomotion

The ability of a bacterium to move toward nutrients or away from toxins is facilitated by a process known as chemotaxis. This movement is powered by the rotation of the flagellum, which can reach speeds of several hundred revolutions per second. The motor is not powered by ATP directly but by a proton motive force, where a gradient of protons (or sometimes sodium ions) across the inner membrane flows through the stator proteins to turn the rotor.

The architectural complexity of the flagellum varies between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria due to the differences in their cell envelopes. Gram-negative bacteria require a more elaborate basal body with four rings (L, P, MS, and C) to penetrate both the inner and outer membranes and the thin peptidoglycan layer. In contrast, Gram-positive bacteria, which lack an outer membrane, possess a simpler basal body typically consisting of only two rings anchored in the inner membrane and the thick cell wall.

Core components of the flagellar system include:

- Flagellin subunits that self-assemble at the distal tip of the filament.

- The switch complex (C-ring) that determines clockwise or counter-clockwise rotation.

- The Type III secretion system, which is a structural relative of the “injectisome” found in many virulent pathogens.

- The flexible hook that allows the propeller to function regardless of the cell’s orientation.

From a physiological perspective, the flagellum is a highly metabolic investment for the cell. The production and operation of these structures are tightly regulated by the bacterium’s genetic program, ensuring that flagella are only synthesized when environmental conditions necessitate motility.

Anatomical Differentiation and Clinical Significance

The structural components of the flagellum are often the first points of interaction between a pathogen and the human immune system. Flagellin, the protein that makes up the filament, is a potent Pathogen-Associated Molecular Pattern (PAMP) that is recognized by Toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5) on human cells. This recognition triggers an innate immune response, leading to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines that attempt to neutralize the invading microbes.

In Gram-negative pathogens such as Salmonella or Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the flagellum is more than just a motor; it is a critical virulence factor. It allows these bacteria to swim through mucosal layers and reach epithelial surfaces for attachment. Furthermore, the base of the flagellum shares deep evolutionary roots with the Type III Secretion System (T3SS), a specialized apparatus used by many bacteria to inject effector proteins directly into host cells, subverting cellular processes and facilitating infection.

The intricate coordination required to build and operate a flagellum represents one of the most complex tasks a bacterial cell can perform. By understanding the minute differences in basal body rings and the physiological reliance on ion gradients, medical researchers can develop novel strategies to inhibit bacterial motility. Disrupting the flagellar motor could potentially “paralyze” pathogens, preventing them from colonizing tissues or forming resilient biofilms, thereby offering new avenues for treating multi-drug-resistant infections.