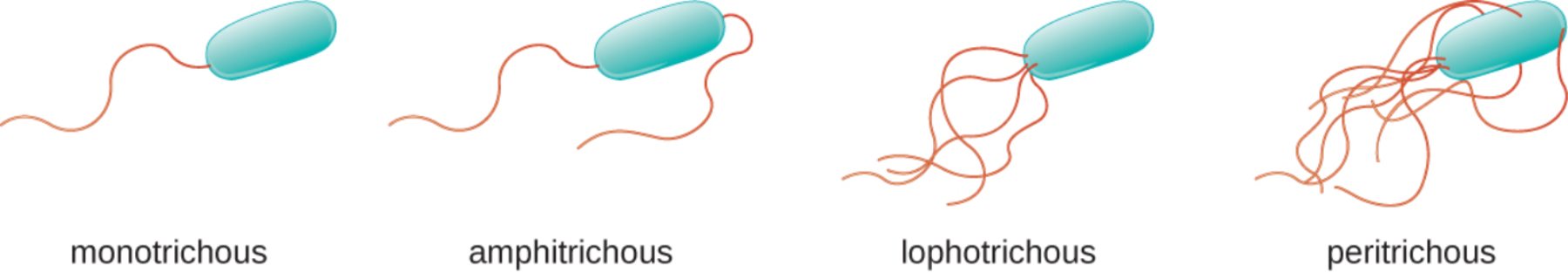

Bacterial motility is a critical adaptation that allows microorganisms to thrive in diverse and often hostile environments. This movement is primarily facilitated by flagella, which are complex, whip-like protein appendages that rotate like propellers to drive the cell forward. The specific distribution of these flagella—known as monotrichous, amphitrichous, lophotrichous, or peritrichous arrangements—is not only essential for locomotion but also serves as a vital taxonomic marker in clinical microbiology.

monotrichous: This arrangement features a single flagellum located at one pole of the bacterial cell. It is commonly observed in species like Vibrio cholerae, providing them with high-speed directional swimming capabilities during the initial stages of pathogenesis.

amphitrichous: In this configuration, the bacterium possesses a single flagellum or small tufts of flagella at both opposite ends of the cell. This dual-polar arrangement allows the organism to change its trajectory or reverse direction rapidly by simply alternating the rotational direction of its appendages.

lophotrichous: This term describes a bacterium that has a cluster or “tuft” of flagella emerging from a single point or pole on the cell body. These multiple flagella often bundle together to act as a powerful engine, propelling the cell through relatively viscous biological fluids.

peritrichous: This pattern involves flagella that are distributed more or less uniformly over the entire surface of the bacterial body. Organisms with this arrangement can coordinate these multiple appendages to perform complex maneuvers, which are fundamental to their survival.

The Physiology of Bacterial Locomotion

The ability of a bacterium to move toward favorable nutrients or away from toxic substances is an essential biological process known as chemotaxis. This directed movement is powered by a molecular motor anchored within the cell envelope. Unlike eukaryotic flagella, which lash back and forth, bacterial flagella are rigid, helical structures that rotate at high speeds. This rotation is driven by the flow of ions, typically protons, across the plasma membrane, creating what is known as the proton motive force.

Microbiologists categorize these movement patterns to identify unknown pathogens in clinical specimens. For instance, the specific way a bacterium “swims” or “tumbles” in a hanging-drop preparation can give immediate clues about its identity before more complex genetic testing is performed. The structural arrangement of flagella determines whether a cell moves in smooth, straight-line “runs” or executes sharp “tumbles” to reorient itself.

Common arrangements of flagellar appendages include:

- Polar arrangements (monotrichous, lophotrichous, and amphitrichous), where flagella are located at the ends of the cell.

- Non-polar arrangements (peritrichous), where flagella cover the entire surface.

- Endoflagella (axial filaments), found in spirochetes, which reside within the periplasmic space.

- Atrichous states, where the bacterium lacks flagella entirely and is non-motile.

The structural components of the flagellum itself are made primarily of the protein flagellin. This protein is a potent stimulus for the human immune system, often recognized by Toll-like receptors that trigger inflammatory cascades. Consequently, the study of flagellar arrangements is not only a matter of cell anatomy but also a key component in understanding how the host body detects and responds to invading microbes.

Biomechanics and Environmental Navigation

The physical layout of flagella is optimized for the specific niche an organism occupies. Monotrichous bacteria are often found in aquatic environments where rapid, straight-line speed is advantageous. In contrast, peritrichous bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, are expertly adapted for life in the nutrient-rich but crowded environment of the human gut. Their ability to rotate their many flagella in a bundle allows for efficient swimming, while reversing the rotation of just one flagellum can cause the bundle to fly apart, initiating a tumble that helps them search for higher concentrations of glucose or amino acids.

The coordination of microbial motility involves complex signaling pathways that integrate inputs from various chemical receptors on the cell surface. These signals are transmitted to the flagellar motor, which acts as a biological switch. By adjusting the duration of runs versus tumbles, the bacterium effectively performs a “biased random walk,” ensuring that it eventually moves in the direction of a favorable environment.

In summary, the diverse arrangements of bacterial flagella represent a masterclass in evolutionary engineering. From the single, high-speed polar flagellum of a Vibrio species to the surface-covering array of an E. coli cell, these structures are perfectly tuned for life on a microscopic scale. Understanding these patterns provides clinicians with a deeper insight into how bacteria colonize tissues, evade immune detection, and ultimately contribute to the complex landscape of human health and disease.