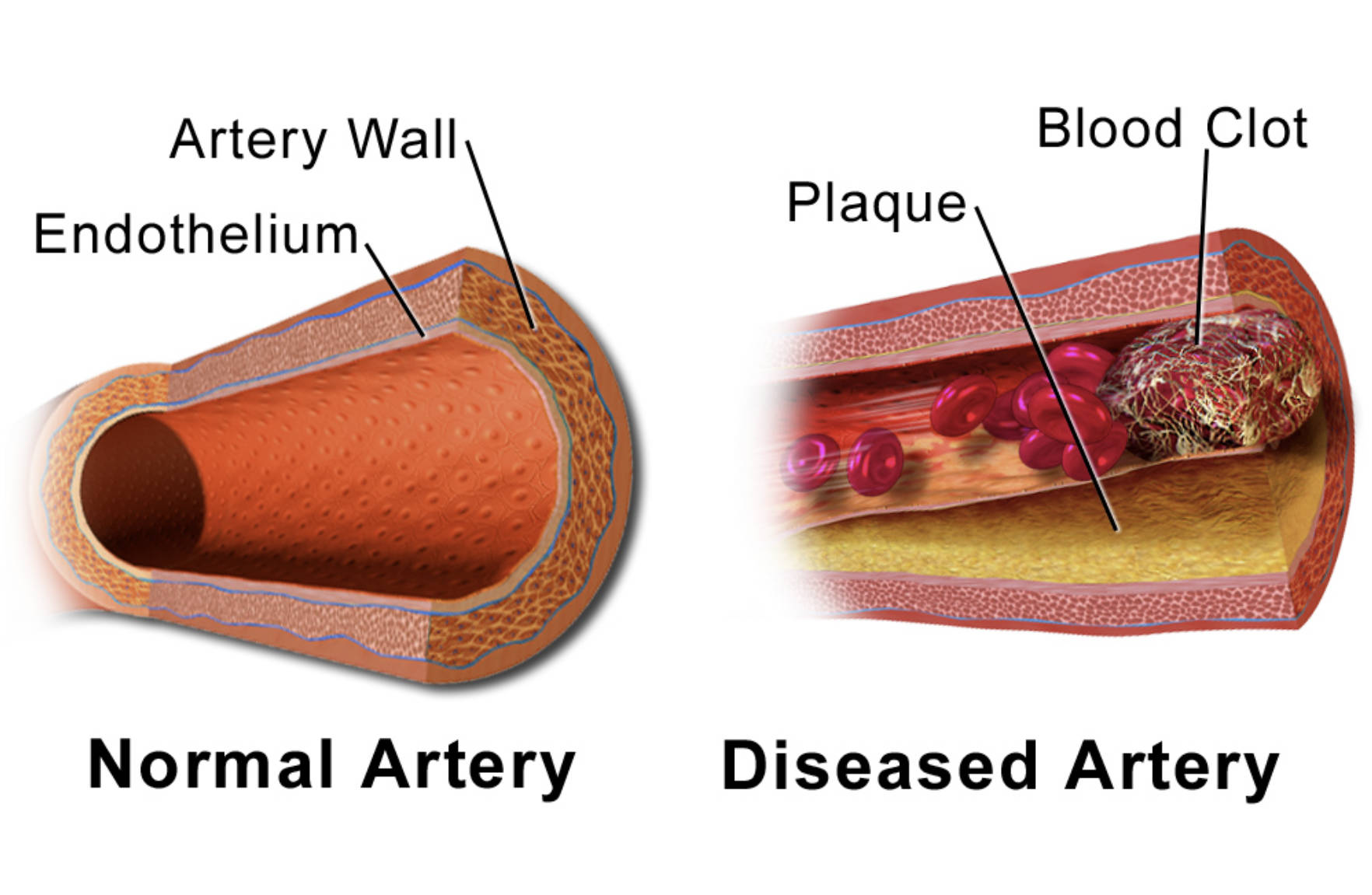

The human vascular system relies on a network of flexible, unobstructed tubes to transport oxygen-rich blood to vital organs, but this system can be compromised by the gradual progression of arterial disease. This article analyzes a comparative diagram of a normal artery versus a diseased artery, highlighting the structural changes caused by cholesterol accumulation and the acute danger of thrombus formation. Understanding these anatomical differences is essential for recognizing the risks associated with cardiovascular conditions such as atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease.

Endothelium: This is the innermost layer of the arterial wall, consisting of a single layer of specialized cells that create a smooth surface to facilitate blood flow. In a healthy state, the endothelium releases substances that control vascular relaxation and prevent blood cells from sticking to the vessel wall.

Artery Wall: This structure is composed of multiple layers, including smooth muscle and connective tissue, which provide the vessel with strength and elasticity. These layers allow the artery to expand and contract in response to the pumping of the heart, effectively managing blood pressure.

Normal Artery: The image on the left depicts a healthy vessel with a wide, open lumen and intact structural layers. In this state, blood flows freely without turbulence or obstruction, ensuring efficient oxygen delivery to tissues.

Plaque: Shown in the diseased artery, this yellow deposit is a buildup of cholesterol, fatty substances, cellular waste products, calcium, and fibrin. Over time, this accumulation hardens and narrows the artery, a condition known as stenosis, which restricts blood flow.

Blood Clot: Also known as a thrombus, this mass of coagulated blood forms when a plaque deposit ruptures or the endothelial lining is damaged. The clot can rapidly obstruct the already narrowed vessel, potentially cutting off blood supply entirely to downstream tissues.

Diseased Artery: The image on the right illustrates a vessel compromised by atherosclerosis, characterized by thickened walls and a narrowed interior. This pathological state represents a significant health risk, as the restricted blood flow and potential for blockage can lead to critical events like heart attacks or strokes.

The Progression of Vascular Disease

The health of the arterial system is the foundation of overall cardiovascular well-being. Arteries are not merely passive pipes; they are dynamic organs that respond to the body’s metabolic needs. A healthy artery is distinctively elastic, capable of stretching with every heartbeat (systole) and recoiling during the resting phase (diastole). This elasticity cushions the high pressure generated by the heart. As seen in the diagram, the integrity of the inner lining, or endothelium, is paramount. When intact, it acts as a non-stick coating, ensuring that blood cells and platelets glide smoothly through the vessel.

However, this delicate system is vulnerable to damage from various physiological stressors. When the endothelium is injured—often due to high blood pressure, smoking, or high blood sugar—it becomes permeable to Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. The body launches an immune response, sending white blood cells to the site. These cells engulf the cholesterol but eventually die, accumulating to form the fatty deposits known as plaque. This process, known as atherosclerosis, transforms the flexible artery into a rigid, narrowed tube.

The danger of this condition lies not only in the gradual narrowing of the vessel but in the volatility of the plaque itself. As illustrated in the “Diseased Artery” section of the diagram, the plaque takes up significant space within the vessel wall. Risk factors that accelerate this process include:

- Hypertension (High Blood Pressure): The physical force damages the arterial lining.

- Hyperlipidemia: High levels of cholesterol provide the raw material for plaque.

- Smoking: Chemicals in tobacco smoke are toxic to the endothelium and promote clotting.

- Diabetes: High glucose levels stiffen blood vessels and accelerate plaque formation.

Pathophysiology of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis

The transition from a stable plaque to an acute medical emergency is often triggered by the rupture of the plaque’s surface. Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease. The plaque, which resides within the artery wall, is covered by a fibrous cap. If inflammation weakens this cap, it can tear or rupture. When the inner core of the plaque—rich in lipids and inflammatory material—is exposed to the bloodstream, the body perceives it as an injury.

This triggers the coagulation cascade, a rapid physiological response intended to stop bleeding. Platelets rush to the site and adhere to the rupture, and fibrin strands weave through them to form a mesh. While this mechanism is life-saving in the event of an external cut, inside a narrowed artery, it is catastrophic. The resulting thrombus (blood clot) can grow within minutes, as shown in the diagram, filling the remaining space in the lumen.

If this occurs in a coronary artery supplying the heart muscle, the result is a myocardial infarction (heart attack). If it occurs in a vessel supplying the brain, it causes an ischemic stroke. The blood clot depicted is a dense mesh of red blood cells trapped in fibrin, acting as a physical dam. This acute occlusion explains why a person with manageable arterial disease can suddenly experience a life-threatening event. The physiology changes instantly from restricted flow (ischemia) to zero flow (infarction), leading to rapid tissue death downstream from the blockage.

Prevention and Clinical Management

Understanding the anatomy of a diseased artery highlights the importance of preventative medicine. Because the initial stages of plaque formation are asymptomatic, the disease often progresses silently for decades. Medical intervention focuses on two main goals: stabilizing the plaque to prevent rupture and managing the risk factors that damage the endothelium. Medications such as statins are frequently prescribed to lower cholesterol levels and reduce inflammation within the plaque, making the fibrous cap stronger and less likely to burst. Antiplatelet medications may also be used to make the blood less prone to inappropriate clotting.

Conclusion

The visual contrast between a normal and a diseased vessel serves as a stark reminder of the biological consequences of lifestyle and genetic risk factors. While a normal artery facilitates life by delivering oxygen, a diseased artery harbors the potential for sudden vascular occlusion. Recognizing the link between plaque accumulation and blood clot formation allows patients and healthcare providers to prioritize vascular health through diet, exercise, and medical management, ultimately preventing the catastrophic outcomes associated with advanced arterial disease.