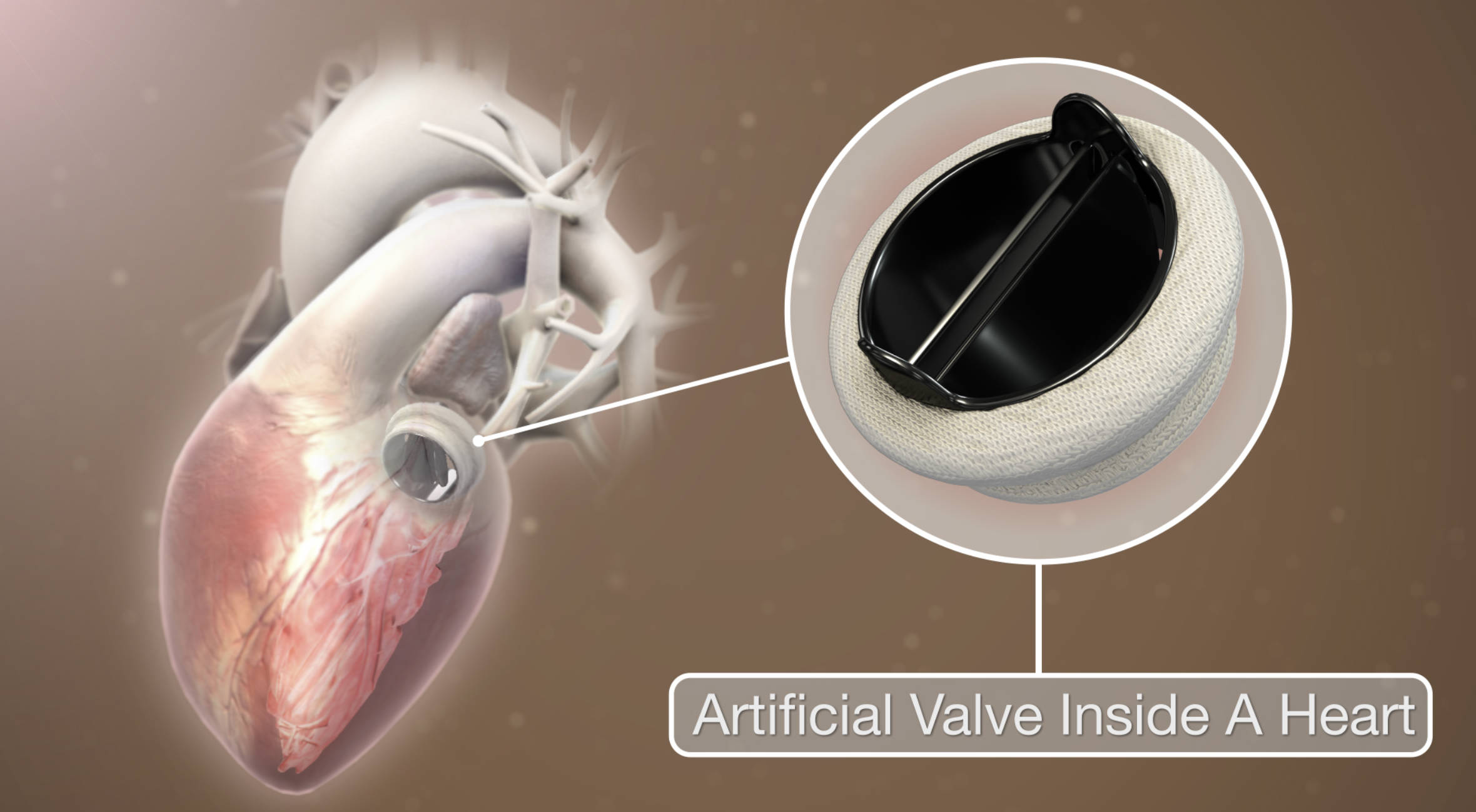

Heart valve replacement is a critical surgical intervention designed to restore proper hemodynamics in patients suffering from severe structural heart defects. This detailed 3D medical illustration highlights the precise placement of a mechanical artificial valve within the cardiac architecture, demonstrating how modern biomedical engineering can replicate natural physiology to prevent heart failure and significantly improve a patient’s longevity.

Artificial Valve Inside A Heart: This label points to a prosthetic device, specifically a mechanical bileaflet valve, which has been surgically implanted to replace a damaged native valve. The device features two semi-circular leaflets housed within a sturdy ring that open and close in response to pressure changes, ensuring blood flows in only one direction while preventing backflow or regurgitation.

The Role of Prosthetic Valves in Cardiac Health

The human heart relies on four essential valves—the tricuspid, pulmonary, mitral, and aortic—to act as one-way gates, ensuring efficient blood circulation throughout the body. When one of these valves becomes diseased or damaged, the heart must work harder to pump blood, leading to fatigue, shortness of breath, and eventually, heart failure. Artificial heart valves are the primary solution for restoring this function when repair is not possible.

There are two main categories of prosthetic valves: biological (tissue) valves and mechanical valves. The image above specifically depicts a mechanical heart valve, typically constructed from robust materials like titanium and pyrolytic carbon. Unlike tissue valves, which are derived from animal donors and may wear out over 10 to 15 years, mechanical valves are designed to be incredibly durable and can last the remainder of a patient’s life. This makes them an ideal choice for younger patients who want to avoid reoperation.

The specific design shown is a bileaflet valve, which is the most common type of mechanical valve used today. It consists of two semicircular leaflets that pivot on hinges. When the heart contracts, the leaflets open to allow blood to pass; when the heart relaxes, they snap shut to prevent leaks. A fabric “sewing ring” surrounds the metal housing, providing a secure anchor point for the surgeon to suture the device into the heart tissue.

Key advantages of mechanical heart valves include:

- Superior Durability: They do not degrade over time like biological tissue.

- Hemodynamic Efficiency: Modern designs minimize resistance to blood flow.

- Reduced Reoperation Risk: Their longevity often eliminates the need for future valve replacement surgeries.

Understanding Valvular Heart Disease

The implantation of an artificial valve is usually necessitated by valvular heart disease, a condition characterized by damage to or a defect in one of the four heart valves. This disease generally presents in two forms: stenosis and regurgitation. In stenosis, the valve opening narrows and becomes stiff, often due to calcium buildup or scarring. This forces the heart to pump with excessive force to push blood through the restricted opening. In regurgitation, the valve leaflets fail to close completely, allowing blood to leak backward into the heart chamber it just left.

Aortic stenosis is one of the most common reasons for the surgery depicted in the image. As the aortic valve calcifies with age, the left ventricle must generate immense pressure to eject blood into the aorta. Over time, the heart muscle thickens (hypertrophy) and weakens. Symptoms often include chest pain (angina), fainting spells (syncope), and severe breathlessness during exertion. Without surgical intervention to replace the narrowed valve with a prosthetic one, the prognosis for severe symptomatic aortic stenosis is poor.

Post-Surgical Management and Anticoagulation

While mechanical valves offer the benefit of lifelong durability, they introduce a specific physiological challenge: the risk of blood clots. The materials used in these valves, while biocompatible, are foreign to the body. Blood has a natural tendency to clot when it comes into contact with the artificial surfaces of the valve mechanism. If a clot forms on the valve (thrombosis), it can jam the leaflets or break loose and travel to the brain, causing a stroke.

To mitigate this risk, patients with mechanical valves require lifelong anticoagulation therapy, commonly involving a medication known as warfarin. Managing this therapy requires regular blood tests to monitor the International Normalized Ratio (INR), ensuring the blood is thin enough to prevent clots but thick enough to prevent excessive bleeding. Patients must also be mindful of their diet, specifically their intake of Vitamin K, which can affect how blood thinners work. Despite this requirement, the trade-off is often considered acceptable for the structural reliability the mechanical valve provides.

Conclusion

The development of the artificial heart valve stands as one of the most significant achievements in modern cardiovascular surgery. By effectively replacing a failing anatomical structure with a durable mechanical equivalent, surgeons can reverse the debilitating effects of heart valve disease. Whether through the robust design of a mechanical valve or the biocompatibility of a tissue valve, these devices provide patients with a second chance at an active, healthy life.