This article provides a comprehensive overview of aortic regurgitation (AR), a specific type of valvular heart disease, as illustrated by the provided anatomical diagram. We will delve into the critical function of the aortic valve, explain how its malfunction leads to inefficient blood flow, and discuss the subsequent physiological consequences on the heart’s pumping efficiency and overall cardiovascular health.

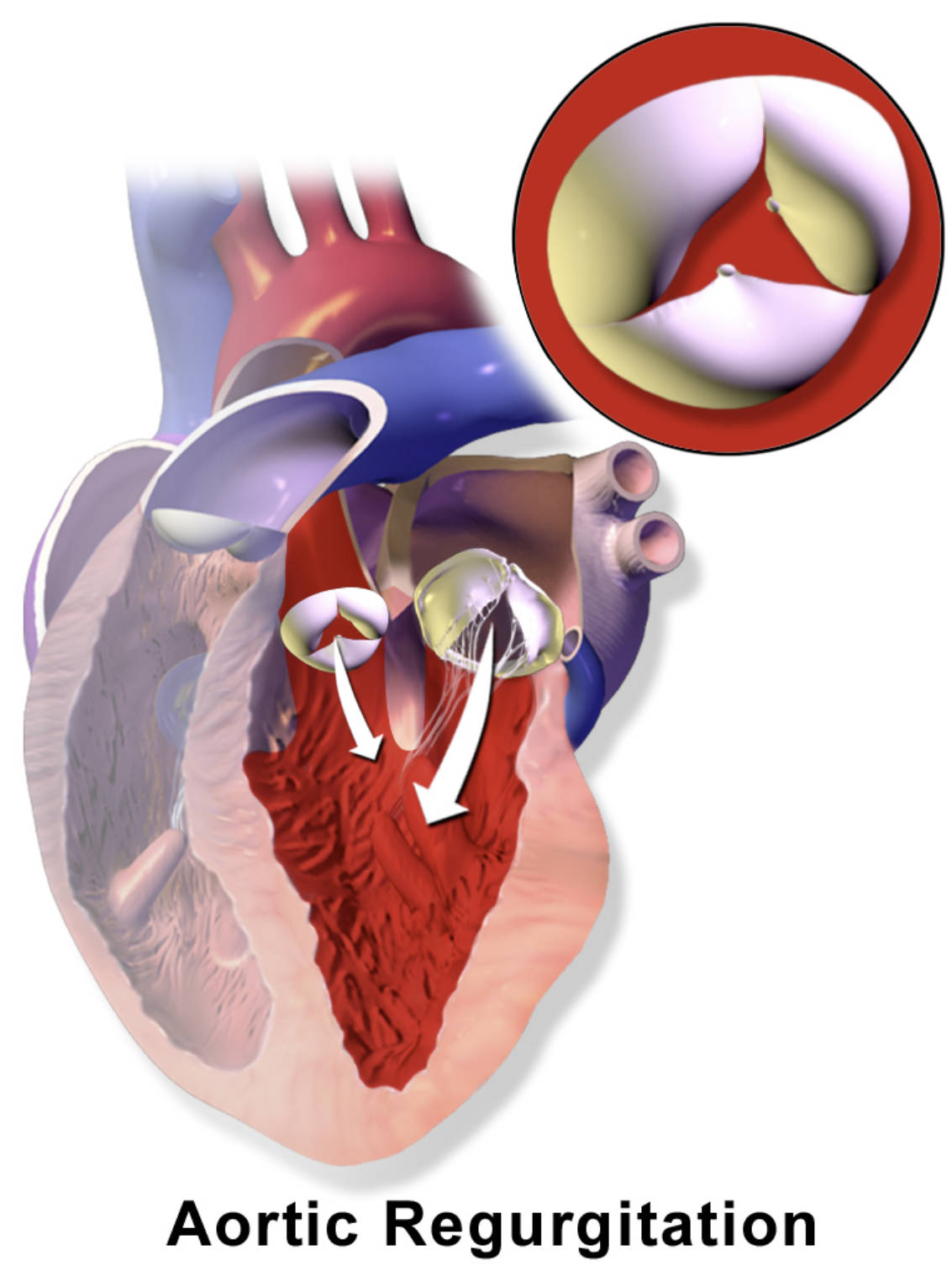

The provided diagram clearly illustrates the condition of aortic regurgitation, where the aortic valve fails to close completely. This allows a portion of the blood to leak back into the left ventricle from the aorta after it has been pumped out. This inefficiency forces the left ventricle to work harder to maintain adequate forward blood flow to the body.

The aortic valve is a crucial component of the heart’s circulatory system, positioned between the left ventricle and the aorta. Its primary role is to ensure that oxygen-rich blood, once pumped out of the left ventricle, flows unidirectionally into the aorta and then to the rest of the body. When the aortic valve malfunctions by failing to close properly, it results in aortic regurgitation, also known as aortic insufficiency. This condition leads to a backward flow of blood into the left ventricle, creating a significant volume overload for the heart.

The diagram vividly depicts this abnormal backflow, indicated by the white arrows pointing into the left ventricle. This retrograde flow means that the left ventricle not only has to pump the normal volume of blood received from the left atrium but also the additional volume that leaks back from the aorta. This chronic volume overload places immense stress on the left ventricle, leading to its dilation and hypertrophy over time as it attempts to compensate and maintain cardiac output.

Understanding the specific mechanisms of aortic regurgitation is essential for appreciating its clinical manifestations and the rationale behind various treatment strategies. The causes of AR are diverse, ranging from acute conditions to chronic degenerative processes:

- Acute AR can result from endocarditis, aortic dissection, or trauma.

- Chronic AR often stems from rheumatic fever, congenital bicuspid aortic valve, hypertension, or degenerative changes.

These underlying pathologies disrupt the valve’s integrity, leading to its inability to coapt fully during diastole.

The Physiology of Aortic Regurgitation

In a healthy heart, during diastole (the relaxation phase when the ventricles fill with blood), the aortic valve is tightly closed, preventing any backflow from the aorta into the left ventricle. This ensures that the left ventricle fills exclusively with oxygenated blood from the left atrium. However, with aortic regurgitation, the incompetent aortic valve allows a fraction of the ejected blood to flow backward into the left ventricle during diastole. This extra volume of blood, combined with the normal inflow from the left atrium, significantly increases the preload on the left ventricle.

To accommodate this increased volume and maintain adequate forward blood flow to the systemic circulation, the left ventricle undergoes adaptive changes. It dilates, meaning its chamber size increases, and its walls thicken (eccentric hypertrophy). While these compensatory mechanisms can maintain normal cardiac output for many years, they eventually become insufficient. The chronic volume overload and increased workload lead to progressive left ventricular dysfunction, impaired contractility, and ultimately, heart failure. The characteristic “bounding” pulse (Corrigan’s pulse) and a wide pulse pressure (a large difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressure) are clinical signs often associated with severe AR, reflecting the large stroke volume and rapid runoff of blood from the aorta.

Causes and Clinical Manifestations

Aortic regurgitation can arise from abnormalities of the aortic valve leaflets themselves or from dilation of the aortic root, which prevents the leaflets from coapting properly. Common causes of chronic aortic regurgitation include:

- Congenital bicuspid aortic valve: A valve with two leaflets instead of the usual three, making it more prone to dysfunction.

- Rheumatic heart disease: An inflammatory condition that can damage heart valves.

- Hypertension: Chronic high blood pressure can lead to dilation of the aortic root.

- Degenerative calcific disease: Age-related wear and tear leading to leaflet stiffening.

- Marfan syndrome and other connective tissue disorders: These can cause dilation of the aortic root.

Acute aortic regurgitation is a medical emergency often caused by endocarditis (infection of the valve), aortic dissection (a tear in the aortic wall), or trauma. Symptoms of chronic AR often develop gradually over many years. Patients may remain asymptomatic for a long time, but as the condition progresses, they can experience fatigue, shortness of breath, especially with exertion or when lying flat (orthopnea), palpitations, and chest pain (angina pectoris), particularly at night. In acute AR, symptoms are typically severe and abrupt, including sudden onset of shortness of breath and cardiogenic shock.

Diagnosis and Management Strategies

Diagnosing aortic regurgitation involves a combination of clinical assessment, physical examination, and imaging studies. During a physical exam, a physician may detect a characteristic diastolic decrescendo murmur, heard best along the left sternal border. An echocardiogram is the cornerstone of diagnosis, providing detailed information about the severity of regurgitation, the structure and function of the aortic valve, the size and function of the left ventricle, and the dimensions of the aorta. Cardiac MRI can also provide comprehensive assessment of left ventricular volumes and aortic root anatomy.

Management of AR depends on the severity of the regurgitation, the presence of symptoms, and the degree of left ventricular dysfunction. For asymptomatic patients with mild to moderate AR and preserved left ventricular function, careful monitoring with regular echocardiograms is usually sufficient. Medications such as vasodilators (e.g., ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers) may be used to reduce afterload and slow the progression of ventricular dilation. However, definitive treatment for severe AR, especially in symptomatic patients or those with evidence of left ventricular dysfunction, is surgical. This involves either aortic valve repair or, more commonly, aortic valve replacement with a mechanical or bioprosthetic valve. Surgical timing is critical to prevent irreversible damage to the left ventricle and ensure optimal long-term outcomes for patients.