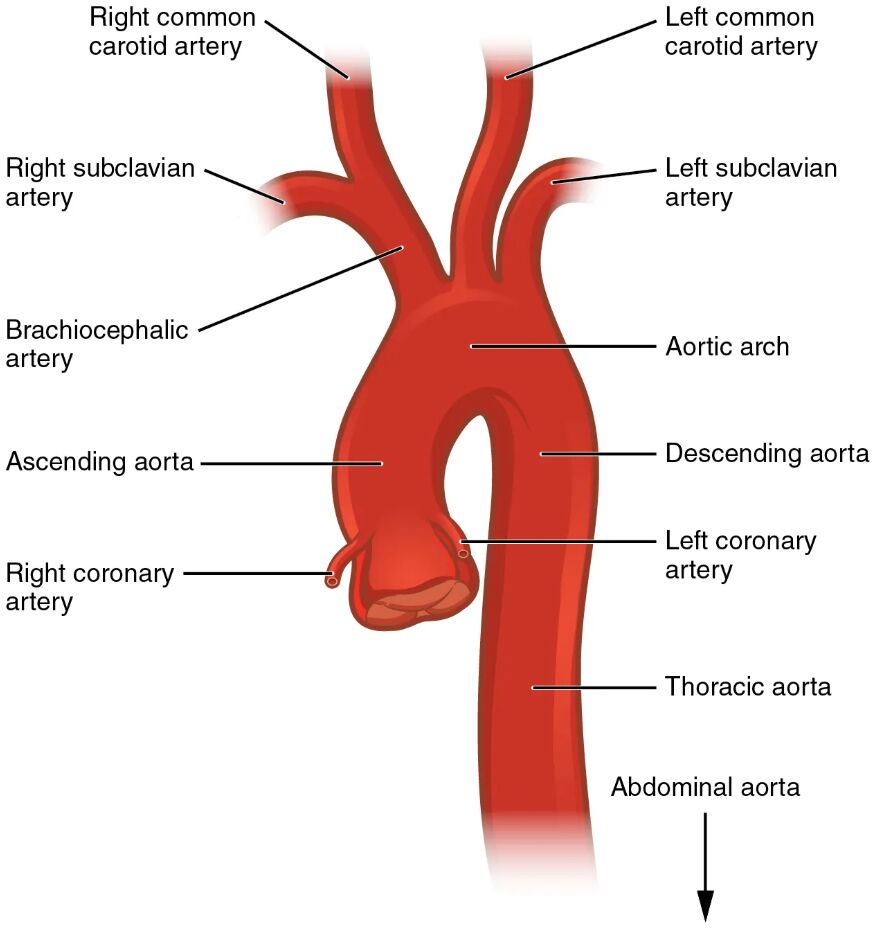

The aorta, the body’s largest artery, serves as the primary conduit for distributing oxygenated blood from the heart to all tissues. This diagram details its distinct regions—ascending aorta, aortic arch, and descending aorta, including thoracic and abdominal segments—highlighting its critical role in systemic circulation.

Ascending aorta This initial segment rises from the left ventricle, carrying oxygenated blood away from the heart. It gives rise to the coronary arteries that supply the heart muscle.

Aortic arch Curving between the ascending and descending aorta, this section distributes blood to the head and upper limbs. It branches into the brachiocephalic, left common carotid, and left subclavian arteries.

Descending aorta This major portion extends downward from the aortic arch, delivering blood to the chest, abdomen, and lower body. It is subdivided into thoracic and abdominal regions for targeted circulation.

Thoracic aorta Located in the chest, this segment supplies blood to the lungs, esophagus, and other thoracic structures. Its branches ensure oxygen delivery to the upper body’s internal organs.

Abdominal aorta Positioned in the abdomen, it provides blood to the digestive organs, kidneys, and lower limbs. It branches into major arteries like the celiac trunk and renal arteries.

Brachiocephalic artery Arising from the aortic arch, it supplies the right arm and right side of the head and neck. It splits into the right subclavian and right common carotid arteries.

Left common carotid artery This branch from the aortic arch delivers blood to the left side of the head and neck. It ensures oxygen supply to the brain and facial tissues.

Left subclavian artery Originating from the aortic arch, it provides blood to the left arm and shoulder. It supports upper limb function and circulation.

Celiac trunk Branching from the abdominal aorta, it supplies the stomach, liver, and spleen. It plays a key role in nutrient absorption and blood filtration.

Superior mesenteric artery This abdominal aorta branch feeds the small intestine and part of the large intestine. It supports digestion and nutrient uptake in the gastrointestinal tract.

Renal arteries Emerging from the abdominal aorta, they supply the kidneys with blood. They are essential for filtration, waste removal, and blood pressure regulation.

Inferior mesenteric artery This artery from the abdominal aorta serves the lower large intestine. It ensures blood flow for waste elimination and lower digestive function.

Common iliac arteries Splitting from the abdominal aorta, they supply the pelvis and lower limbs. They are critical for leg movement and pelvic organ perfusion.

Anatomy of the Aorta

The ascending aorta marks the beginning of the systemic arterial system, channeling blood from the heart. Its structure supports the initial high-pressure flow.

- It contains elastic fibers to absorb the force of ventricular contraction.

- The coronary arteries branch off to nourish the heart muscle.

- Its short length transitions smoothly into the aortic arch.

- The vessel’s diameter accommodates the entire cardiac output.

- This segment is prone to dilation if weakened, leading to aneurysms.

Structure and Function of the Aortic Arch

The aortic arch serves as a pivotal junction, directing blood to the upper body. Its curved design facilitates efficient distribution.

- It gives rise to three major arteries: brachiocephalic, left common carotid, and left subclavian.

- The arch’s elasticity helps maintain steady pressure during the cardiac cycle.

- Its position allows gravity-assisted flow to the head and arms.

- Blood flow here is critical for brain oxygenation and upper limb function.

- Narrowing or blockages can impair cerebral or peripheral circulation.

Descending Aorta and Its Divisions

The descending aorta, including thoracic and abdominal regions, delivers blood to the lower body. Each segment adapts to specific anatomical needs.

- The thoracic aorta supplies organs like the lungs and esophagus.

- The abdominal aorta branches extensively to reach visceral and limb areas.

- Its gradual tapering reduces pressure as it descends.

- Elasticity decreases in the abdominal section, increasing vulnerability to disease.

- This division ensures comprehensive coverage of the body’s needs.

Major Branches and Their Roles

The renal arteries and other branches from the abdominal aorta play specific roles in organ support. Their functions are tailored to regional demands.

- Renal arteries ensure kidney filtration and hormone production like renin.

- The celiac trunk supports digestion by feeding the liver and stomach.

- Superior and inferior mesenteric arteries nourish the intestines.

- Common iliac arteries extend circulation to the pelvis and legs.

- These branches adjust flow based on metabolic activity or posture.

Clinical Significance of Aortic Anatomy

Understanding the aorta’s structure aids in diagnosing and treating vascular conditions. Its anatomy guides medical and surgical approaches.

- Aneurysms in the ascending aorta require monitoring due to rupture risk.

- Blockages in the aortic arch can lead to stroke or arm ischemia.

- Renal arteries issues may cause hypertension or renal failure.

- Abdominal aortic aneurysms are a common concern in older adults.

- Imaging like CT scans maps these arteries for intervention planning.

The aorta, with its ascending aorta, aortic arch, and descending aorta, forms the backbone of the systemic circulation, delivering oxygenated blood efficiently. Its intricate branching ensures every organ receives vital nutrients, offering a foundation for exploring cardiovascular health and addressing related challenges.