Understanding the Anatomy of the Lymphatic System: Structure, Components, and Functions

The lymphatic system plays a crucial role in maintaining the body’s fluid balance, defending against infections, and absorbing dietary fats from the intestines. Comprising a network of vessels, nodes, and organs, it works closely with the cardiovascular system to filter out harmful substances and support immune responses, ensuring overall health and homeostasis.

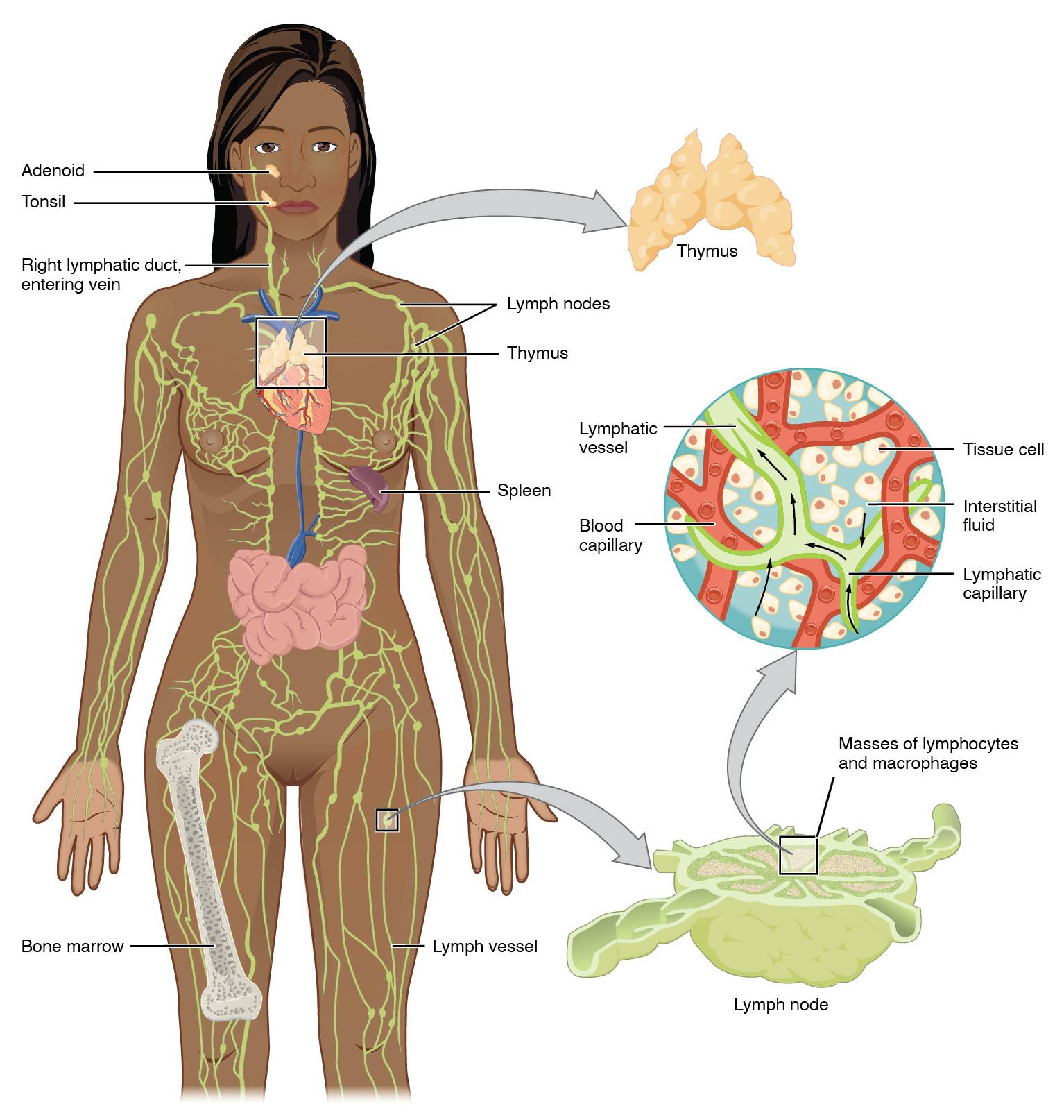

Key Labeled Components in the Lymphatic System Diagram

This section breaks down each labeled element visible in the diagram, providing clear insights into their locations and roles.

Adenoid The adenoid is a mass of lymphoid tissue located at the back of the nasal cavity, part of the Waldeyer’s ring that helps trap pathogens entering through the nose. It contributes to the immune defense in the upper respiratory tract, particularly during childhood when it is most prominent, and tends to shrink after puberty.

Tonsil The tonsil, specifically the palatine tonsil shown, is situated at the back of the throat and acts as a first line of defense against ingested or inhaled pathogens. These structures contain lymphocytes that detect and respond to antigens, helping to prevent infections in the oral and pharyngeal regions.

Right lymphatic duct, entering vein The right lymphatic duct collects lymph from the right side of the head, neck, and upper limb, draining it into the right subclavian vein to re-enter the bloodstream. This pathway ensures that excess fluid and immune cells are returned to circulation, maintaining fluid balance on the body’s right side.

Lymph nodes Lymph nodes are small, bean-shaped structures scattered throughout the body, filtering lymph fluid to remove foreign particles like bacteria and cancer cells. They house immune cells such as lymphocytes and macrophages, which activate responses to infections and play a key role in adaptive immunity.

Thymus The thymus is a gland located in the upper chest behind the sternum, responsible for the maturation of T-lymphocytes, essential for cell-mediated immunity. It is most active during childhood and gradually involutes with age, but continues to support immune function throughout life.

Spleen The spleen, positioned in the upper left abdomen, filters blood to remove old red blood cells, bacteria, and other debris while also producing antibodies. As the largest lymphoid organ, it stores platelets and white blood cells, contributing to both immune surveillance and hematological functions.

Bone marrow Bone marrow, found within the cavities of bones like the femur shown, is the primary site for hematopoiesis, producing red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. In the context of the lymphatic system, it generates B-lymphocytes and precursors for T-cells, forming the foundation of the immune response.

Lymph vessel Lymph vessels are thin-walled tubes that transport lymph fluid from tissues back to the bloodstream, preventing edema by draining excess interstitial fluid. They contain valves to ensure unidirectional flow and merge into larger ducts that empty into veins near the heart.

Lymphatic vessel Similar to lymph vessels, the lymphatic vessel depicted in the inset illustrates the network’s role in fluid transport at a microscopic level. It connects with capillaries to collect fluid, proteins, and lipids that have leaked from blood vessels into tissues.

Blood capillary The blood capillary in the diagram represents the site where fluid exchange occurs between blood and tissues, leading to the formation of interstitial fluid. This structure allows nutrients and oxygen to diffuse out while waste products enter, with excess fluid being picked up by adjacent lymphatic capillaries.

Tissue cell Tissue cells surround the capillaries and are bathed in interstitial fluid, which provides them with nutrients and removes metabolic wastes. In the lymphatic context, these cells interact with immune components in the fluid, alerting the system to potential threats like infections or inflammation.

Interstitial fluid Interstitial fluid is the liquid that fills spaces between cells, derived from blood plasma that has leaked through capillaries. It becomes lymph when absorbed into lymphatic capillaries, carrying proteins, lipids, and immune cells back to circulation.

Lymphatic capillary Lymphatic capillaries are blind-ended tubes with overlapping endothelial cells that allow easy entry of fluid, proteins, and pathogens from tissues. They initiate the lymphatic drainage process, merging into larger vessels to transport lymph toward nodes and ducts.

Masses of lymphocytes and macrophages Masses of lymphocytes and macrophages refer to clusters within lymphoid tissues that actively combat infections by recognizing and destroying antigens. Lymphocytes include B-cells for antibody production and T-cells for direct attack, while macrophages phagocytose debris and present antigens to activate adaptive immunity.

Lymph node As shown in the inset, the lymph node features compartments where immune cells congregate to filter lymph and mount responses. It enlarges during infections due to cell proliferation, serving as a sentinel for detecting systemic threats.

Functions of the Lymphatic System

The lymphatic system complements the circulatory system by managing fluid levels and bolstering defenses. Its intricate network ensures that the body remains protected from daily exposures.

Beyond basic anatomy, the system’s vessels form a one-way pathway that prevents backflow through valves, similar to veins. This mechanism is vital in areas prone to swelling, such as the limbs. Additionally, the absorption of chylomicrons—fat particles—from the intestines occurs via lacteals, specialized lymphatic vessels in the gut, highlighting its role in nutrition.

- Fluid Balance Maintenance: Lymph vessels collect about 3 liters of fluid daily that leaks from blood capillaries, returning it to the venous system to prevent tissue swelling or edema.

- Immune Surveillance: Organs like the spleen and thymus educate and deploy immune cells, enabling rapid responses to pathogens.

- Fat Absorption: In the digestive tract, lymph transports lipids that blood cannot handle efficiently, aiding overall metabolism.

Physiologically, the system relies on muscle contractions and breathing to propel lymph, lacking a dedicated pump like the heart. Disruptions, such as in lymphedema, underscore its importance in daily health.

Primary and Secondary Lymphoid Organs

Primary lymphoid organs are where immune cells mature, setting the stage for lifelong protection. Secondary organs then facilitate encounters with antigens for active immunity.

The thymus, as a primary organ, secretes hormones like thymosin to promote T-cell development, influencing endocrine aspects akin to how the thyroid releases T3 and T4 for metabolism. Bone marrow complements this by producing B-cells.

Secondary structures include lymph nodes and the spleen, where mature cells interact with foreign substances.

- Thymus Maturation Process: T-cells undergo positive and negative selection here to ensure self-tolerance and effectiveness.

- Spleen’s Dual Role: It handles blood filtration while also initiating humoral immunity through B-cell activation.

- Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue (MALT): Including tonsils and adenoids, this protects entry points like the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts.

These organs adapt over time; for instance, the thymus atrophies post-puberty, shifting reliance to peripheral tissues.

Interconnections with Other Body Systems

The lymphatic system integrates seamlessly with the immune and circulatory systems. This synergy allows for comprehensive bodily defense and equilibrium.

Lymph drains into veins near the heart, mixing with blood to recirculate immune factors. The right lymphatic duct and thoracic duct (implied in the diagram) handle this merger, with the latter draining most of the body.

Endothelial cells in lymphatic capillaries express specific receptors for efficient fluid uptake, linking to cellular biology.

- Cardiovascular Link: Prevents hypotension by returning fluid, supporting blood volume.

- Immune System Overlap: Shares cells like dendritic cells that migrate from tissues to nodes.

- Endocrine Influences: Hormones modulate lymphatic function, such as cortisol affecting immune suppression.

Understanding these ties enhances appreciation of holistic physiology.

In summary, the lymphatic system’s anatomy—from vessels to nodes—underpins essential functions in fluid regulation, immunity, and nutrient transport. Regular physical activity and a balanced diet support its efficiency, promoting long-term wellness.