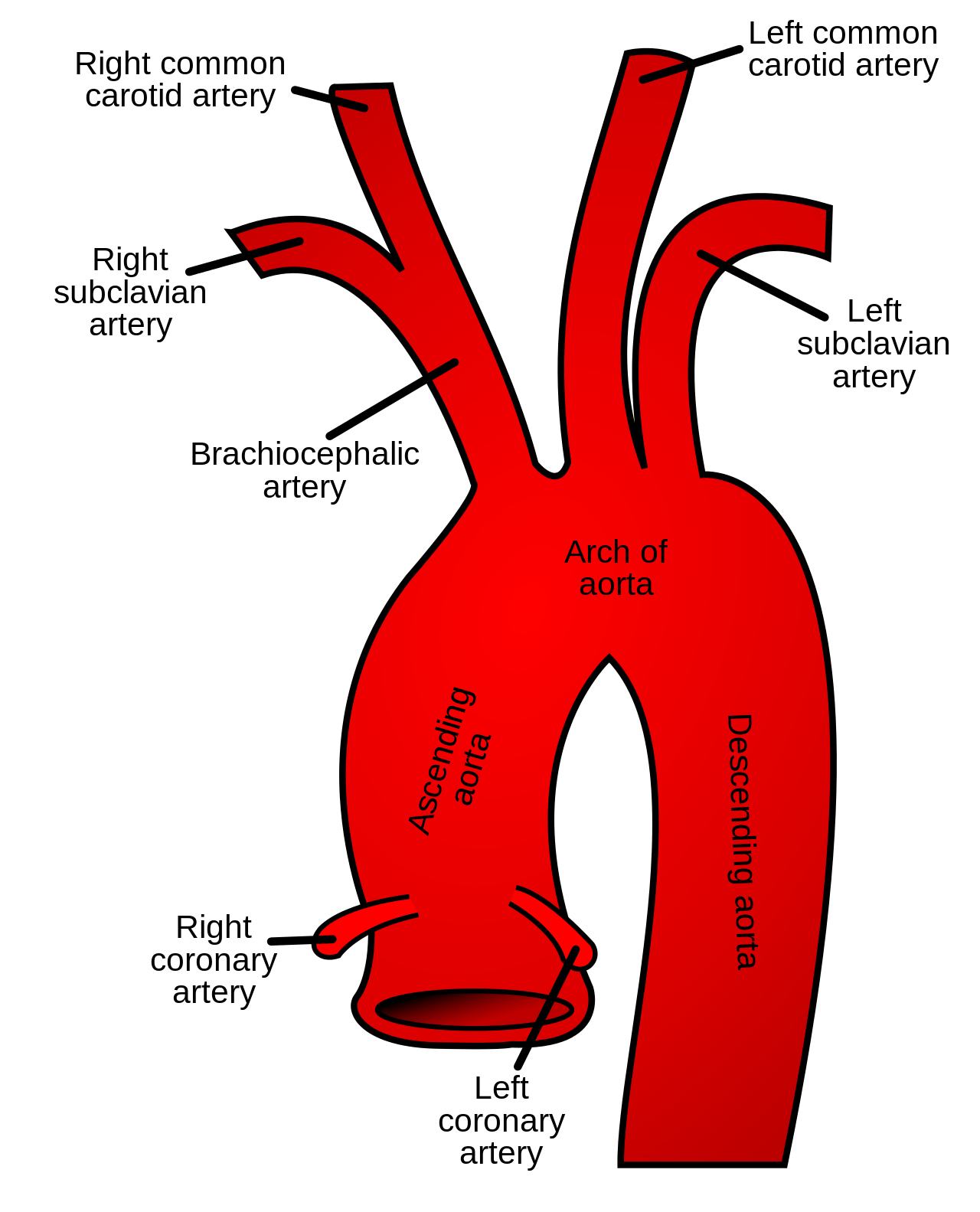

The proximal aorta serves as the primary conduit for oxygenated blood leaving the heart, acting as the structural foundation for systemic circulation. This schematic diagram illustrates the critical transition from the cardiac outlet through the aortic arch, highlighting the major branches that supply the brain, upper limbs, and the heart muscle itself.

Right common carotid artery: This vessel arises from the bifurcation of the brachiocephalic artery. It travels up the right side of the neck to provide essential blood flow to the head and brain.

Right subclavian artery: Originating as the other branch of the brachiocephalic trunk, this artery supplies the right upper extremity. It also gives off several branches that contribute to the blood supply of the neck and thoracic wall.

Brachiocephalic artery: Also known as the innominate artery, it is the first major branch to arise from the aortic arch. It soon divides into the right subclavian and right common carotid arteries.

Arch of aorta: This curved segment connects the ascending and descending portions of the aorta. It is the site where the three major supra-aortic vessels originate to supply the upper body.

Ascending aorta: This is the initial portion of the aorta that emerges directly from the left ventricle of the heart. It contains the aortic sinuses, which give rise to the coronary arteries.

Right coronary artery: Arising from the right aortic sinus, this vessel supplies blood to the right atrium and right ventricle. It plays a crucial role in nourishing the heart’s conduction system, including the SA and AV nodes.

Left coronary artery: This artery originates from the left aortic sinus and typically branches into the left anterior descending and circumflex arteries. It provides the primary blood supply to the left ventricle, the heart’s most muscular chamber.

Left common carotid artery: This vessel is the second branch of the aortic arch. It ascends on the left side of the neck to supply the left side of the head and the brain.

Left subclavian artery: As the third branch of the aortic arch, this artery carries oxygenated blood toward the left arm. It mirrors the function of its right-sided counterpart but originates directly from the aorta.

Descending aorta: This segment begins after the aortic arch and continues downward through the chest and abdomen. It provides blood to the remainder of the body’s organs and lower limbs.

The aorta is the largest artery in the human body, serving as the central highway for oxygen-rich blood. Starting at the left ventricle, it must withstand tremendous pressure during each heartbeat, requiring a wall structure rich in elastic fibers. This elasticity allows the aorta to expand during systole and recoil during diastole, a phenomenon known as the Windkessel effect, which helps maintain continuous blood flow throughout the cardiac cycle even when the heart is relaxing.

Physiologically, the proximal aorta is divided into distinct anatomical regions, each with unique clinical significance. The very base of the ascending aorta contains the aortic valve and the coronary ostia, ensuring the heart receives its own nutrient supply before any other organ. As the vessel curves into the arch, it distributes blood to the cerebrovascular and upper peripheral systems through its three primary branches.

Essential functions of the proximal aorta include:

- Regulating systemic blood pressure through elastic distension and recoil.

- Supplying oxygenated blood to the myocardium via the coronary arteries.

- Providing the primary blood supply to the central nervous system through the carotid arteries.

- Acting as a hemodynamic buffer for the high-velocity blood ejected by the left ventricle.

Histology and Hemodynamics of the Aortic Wall

The structural integrity of the aorta is maintained by three distinct layers: the tunica intima, tunica media, and tunica adventitia. The tunica media is particularly thick in the proximal aorta, containing high concentrations of elastin to facilitate the vessel’s high-compliance nature. This protein allows the vessel to accommodate the stroke volume of the left ventricle without causing excessive spikes in systolic blood pressure. Any weakening in these layers, often due to aging or genetic conditions, can lead to life-threatening complications such as aneurysms or dissections.

Hemodynamically, the branching pattern of the aortic arch is subject to significant anatomical variation among individuals. While the standard three-branch configuration shown in the schematic is the most prevalent, clinicians must be aware of variants such as the “bovine arch,” where the left common carotid shares a common origin with the brachiocephalic artery. Understanding these landmarks and their variations is vital for interventional procedures, such as cardiac catheterization or surgical repair of the aortic root.

Clinical Relevance of Aortic Anatomy

The anatomical relationship between the aorta and surrounding structures, such as the trachea and esophagus, makes it a focal point in thoracic medicine. Because the ascending aorta and the arch are under constant mechanical stress, they are frequent sites for atherosclerotic plaque buildup. Furthermore, the sharp curve of the arch creates unique flow dynamics, where turbulence can contribute to the development of vascular pathologies over time.

In summary, the proximal aorta is much more than a simple tube; it is a dynamic organ that coordinates the distribution of life-sustaining blood. From its origin at the heart to its continuation as the descending aorta, every branch and segment is meticulously designed to meet the metabolic demands of the body. Mastery of this anatomy is the foundation of cardiovascular medicine, enabling precise diagnosis and effective intervention for a wide range of vascular disorders.